Risks

Risks to the regional outlook are tilted to the downside, and include weaker-than-expected recoveries in key trading partner economies, logistical hurdles that further impede vaccine distribution, and scarring of labor productivity that weakens potential growth and income over the longer term.

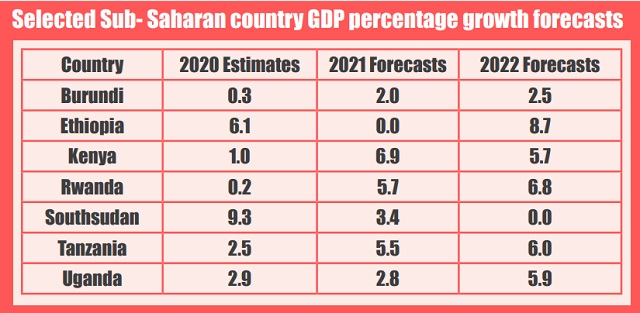

Output in Sub-Saharan Africa contracted by an estimated 3.7 percent—a per capita income decline of 6.1 percent and the deepest contraction on record—as the COVID-19 pandemic and associated lockdown measures disrupted activity through multiple channels.

South Africa suffered the most severe COVID-19 outbreak in Sub-Saharan Africa, which prompted strict lockdown measures and brought the economy to a standstill. With economic activity in South Africa already on a weak footing before the pandemic hit, output is expected to have fallen 7.8% last year.

Africa’s biggest economy, Nigeria, is estimated to have shrunk 4.1 percent in 2020—0.9 percentage point more than previously projected—as the effects of the COVID-19 pandemic and associated measures were worse than expected and affected activity in all sectors.

The deep contraction in activity extended beyond its large economies. Oil exporting countries such as Angola, the Republic of Congo, Equatorial Guinea, and South Sudan have faced sharply lower prices. Equally badly battered have been countries such as Cabo Verde, Ethiopia, Mauritius, and Seychelles that rely heavily on large travel and tourism sectors.

Economic indicators

Exchange rates across the Sub-Saharan region remained about 5% weaker than levels prior to the pandemic, on average, following sharp depreciations in the first half of 2020.

Inflation trends were uneven last year, as persistently soft demand helped contain inflationary pressures in some countries such as Kenya, South Africa, whereas inflation remained elevated, or even accelerated, in response to weaker currencies and food price pressures in others such as Angola, Ethiopia, Ghana, Nigeria, and Senegal.

Rising food prices weighed on households incomes and consumption. This has prompted governments to implement policy measures to improve food provision, support the agriculture sector, and provide cash transfers to the poor. The pace of monetary policy easing across the region slowed in the second half of last year, particularly in countries experiencing inflationary pressures.

Following unprecedented capital outflows in the first half of 2020, the recovery inflows were anemic. In total, FDI flows collapsed by an estimated 30% to 40% last year, while remittance inflows—a vital source of household income and foreign currency receipts—are estimated to have plummeted by 9%.

There was a step-change in government indebtedness in 2020, as economic activity and government revenues sharply fell while pandemic-related spending rose appreciably. Government debt in the region jumped on average 8 percentage points to 70% of GDP.

Government debt in the region is expected to rise further this year, elevating concerns about debt sustainability in some economies. This reflects expectations of persistently wide budget deficits as fiscal revenues remain below pre-pandemic levels, while health and pandemic-related spending needs continue to be elevated.

Moreover, greater interest payment burdens in most economies due to the pickup in indebtedness are bound to further weigh on budget deficits and could undermine required development spending.

In all, 29 Sub-Saharan African countries—of the 44 Debt Service Suspension Initiative (DSSI) country participants—are benefiting from debt relief assistance from official bilateral creditors. Relief amounts to $4.6 billion in debt service suspension—almost half of the total potential DSSI savings. Although the DSSI is providing some breathing room for financially strained economies, some countries such as Angola and Zambia are still struggling to pay their sovereign debts.

Banks may also continue facing sharp increases in non-performing loans as companies struggle to service their debt due to falling revenues.

In cash-strapped economies, governments faced severe difficulties to pay their sovereign debts. As a result, Angola and Zambia have sought to restructure their public debts. Two of Angola’s largest creditors have agreed, outside of the G20 Debt Service Suspension Initiative, to defer the principal payments on Angola’s debt for three years, whereas unsuccessful debt repro-filing discussions contributed to Zambia’s sovereign debt default.

Current account deficits widened in the median economy last year, as collapsing exports; including tourism receipts, exceeded the falls in imports induced by contracting domestic activity in Angola, Gabon, Mauritius, and Rwanda.

Deficits are expected to narrow somewhat in 2021 as improving external demand, as well as firming commodity prices, underpin a recovery in export earnings.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

We haven’t yet seen the effects of elections on covid, so this analysis is premature.

All pictures of the season show lack observance of SOPs.

The pandemic negative effects are expected to shoot up at least one more time before the situation normalises to numbers that will stabilise with normal behaviour.