Museveni’s latest politicking joke or a realistic national target?

When President Yoweri Museveni takes the oath of president for the sixth time on May 12 at Kololo Ceremonial Grounds in Kampala, it appears he will have one goal clearly on his mind: delivering Uganda to the middle income bracket by 2020. If his recent statements are to be taken seriously, this is to be the President’s pet-project this time.

When he organised a luncheon at State House Entebbe on May 4 to thank his outgoing Cabinet, Museveni commended them for ‘almost’ taking Uganda to middle income status.

Sounding optimistic, he said his next term will be much easier, thanks to an expected windfall of oil export dollars.

“By 2019 we shall be getting our oil money. Things that we did by borrowing like infrastructure will be done more easily with our own money,” he said, “We have finished the issue of the pipeline and [we] are going to start exporting our oil.”

According to the World Bank, in the last decade alone, countries that have transited into middle-income status have been boosted by discovery of oil, thanks to global demand especially from China. But some have benefited from a reduction in conflict, structural and political reforms.

The International Monetary Fund (IMF) says effects of the current drop in oil prices could affect the global economy beyond 2018 because such drops in commodity prices often cause negative ripple effects for several years.

Museveni told his outgoing Cabinet that Uganda’s GDP would grow at 6.14% and per capita income rise to $1,039 by 2019 and this would essentially make Uganda leap into the lower-middle income bracket. Museveni could be right.

But just a day before, while speaking in Kampala during the release of the 2016 Regional Economic Outlook report titled: “Sub-Saharan Africa: Time for a policy reset”, the IMF Director for Africa, Antoinette Sayeh had cautioned Uganda against pinning its middle income dream on anticipated oil money. Sayeh cautioned that oil prices are likely to rise slowly and a barrel of oil is unlikely to reach $60 by 2020.

Another economist, Annet Kuteesa, a research fellow, at Makerere University’s Economic Policy Research Institute (EPRC) also says it would not be a good idea to bank on oil because Uganda’s oil reserves will not last a long time.

“Our reserves are very low and will probably last us 20-30 years,” she said, “Oil money will never be enough because our demands as a country are ever-growing.”

Kuteesa says if oil revenues must be relied upon to propel the economy, they must be invested in sectors that have a multiplier effect, including infrastructure, manufacturing, agriculture, and tourism.

Kuteesa’s pessimism is shared by others like Fred Muhumuza; a development economist who thinks the talk of Uganda achieving middle income status by 2020 is a ‘politicking joke.’

“There cannot even be first oil in 2019,” he told The Independent on May 8.

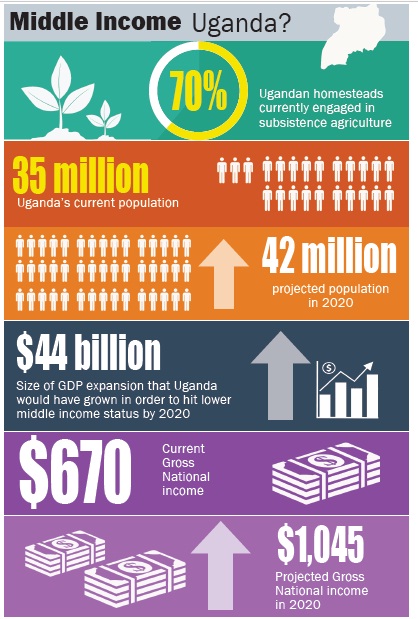

He says for Uganda to reach the minimum threshold of lower middle income, the government would need to generate a GDP of US$ 43.89 billion; an increase of 78% over the next five years. That would have to contend with a population growth rate that adds at least 1.15 million people every year, onto its current 35 million. Uganda would, therefore, hit the 42 million mark in 2020.

“I am yet to see plans of what it will take to get the population to US$ 1,045. There is not even a discussion of the social, economic, institutional and political reforms required to revive the economy.

“With 30% of Ugandans under the international poverty line of less than US$ 1.25 per day, and 63% of Ugandans being vulnerable, the journey to middle income status looks very doubtful,” he says.

But why is attaining middle-income status such a big deal to President Museveni? Isn’t his timeline too ambitious?

“We do not have enough evidence to answer the question,” says Muhumuza, “because we have not even started to discuss the basics.”

Muhumuza says the journey to middle income status is not simply an economic issue to be addressed through the National Development Plan but has significant political, institutional and social aspects.

The real deal or joke?

As the debate rages, officials at the National Planning Authority (NPA)—the agency responsible for charting Uganda’s economic growth path—have set 2020 as the magic date for Uganda to achieve Middle Income Status.

Wilberforce Kisamba Mugerwa, the NPA’s board Chairman says the target is achievable. He points out that GDP growth was a modest 3.1% in 2000 but has since moved up to 5.0% with per capita income rising to over $ 600 from just under $300 at the turn of the millennium.

The NPA plan contains structural transformation benchmarks to ensure that resources are re-allocated from less to more productive sectors.

The government has already set out five priority areas of agriculture, tourism, minerals, oil and gas infrastructure and human capital development as the important sectors that would propel the economy into middle income status.

The government hopes that its emphasis on developing infrastructural hardware, innovation and improved security could fast-track the country’s economic development and elevate it to the desirable economic status.

Officials at NPA also say reduction of production costs, improving electricity supply and putting in place a faster mode of transporting goods and raw materials to and from the East African coast would also help in pushing Uganda forward.

To be a middle income economy, according to the World Bank, a country must have per capita Gross National Income of between $1,045 and above $12,746. Below $4,125 is ‘lower-middle income’; those between $4,125 and $12,746 are “upper middle income”, and those above $12,746 are in the bracket of “high income.”

Based on that computation, oil-producing Equatorial Guinea with a population of under a million people has a per capita income of about $20,500, making it the only high income country on the African continent.

Nigeria, which is Africa’s largest economy with a GDP of over $520 billion, is a lower middle income country; largely because of its large population. About 10 countries are in the upper middle-income category.

These include Angola, Botswana, Algeria, Gabon, Libya, Mauritius, Namibia, Seychelles, Tunisia, and South Africa. Over 15 African countries fall in the lower middle income bracket. They include Ivory Coast, Kenya, Cameroon, DR Congo, Cape Verde, Djibouti, Egypt, Ghana, Lesotho, Morocco, Mauritania, Sudan, Senegal, South Sudan, São Tomé and Principe, Swaziland and Zambia.

To achieve middle income status between now and 2020, Uganda’s economy must consistently grow at rates of 6%. According to knowledgeable observers like Francis Kamulegeya, the Country Senior Partner at the international management firm PricehouseCoopers, that is achievable only if the population growth rate remains at the current 3%.

According to the IMF, Uganda’s GDP growth will not hit the target of 6.3% in the next two years. That is the benchmark growth rate of the second phase of the National Development Plan (NDPII) that is supposed to propel Uganda into a middle income economy. Instead the IMF predicts that the country’s GDP will grow by around 5% in 2015; 5.3% in 2016 and 5.7% in 2017.

Stephen Kaboyo, the Managing Director at Alpha Capital Partners, a local financial advisory firm also told The Independent that Uganda needs improvements in infrastructure, a better business environment; investment in human capital, diversification of the economy to achieve middle income status.

“Achieving the above will not be easy because of capacity and resource constraints,” Kaboyo said.

Other economy experts say that if Uganda is to attain middle income status in a short time, it needs to carefully coordinate its macroeconomic, industrial, financial, and market policies. The economy needs to register consistently higher growth rates than current levels.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Uganda should put 30% of its resource in creating strategic competence and abilities to counter stiff competition ahead, of course people being the most product and important resource uganda has we should therefore invest in them first, I mean creating knowledge that we propel the country to manufacturing nations league and that is posible, with good and knowlegable society.