Exhibits at the Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York, show how cultural cross-pollination thrived across centuries and continents under Byzantine rule

ART | AGENCIES | While trans-continental interventions on the African continent began with the 15th-century arrival of the Portuguese, the Metropolitan Museum of Art’s Africa & Byzantium exhibition demonstrates how the continent had been engaged in cross-regional interaction for much longer. On the northern and north-eastern coasts of Africa, proximity afforded by the Mediterranean, Red and Arabian Seas facilitated exchanges of goods, ideas, belief systems and aesthetic practices.

Byzantium, the vast Roman Empire shifted east and centred in Constantinople (modern-day Istanbul), ruled parts of Europe, Asia and Africa from the fourth to the 15th centuries. Through the link of empire, areas divided by today’s continental and cultural standards shared intimate dialogic histories. In the Met’s new exhibition, these bonds are restored.

The exhibition presents nearly 200 Medieval objects spanning geographies and temporalities usually separated by the museum’s own departmental organisation. Arranged chronologically, the show identifies three crucial periods of artistic development: early Byzantine culture of the fourth to seventh centuries, the rise of Christianity in Africa between the eighth and 16th centuries, and Ethiopian and Coptic art of the 17th to 20th centuries.

The striking introductory mosaic, which also billows on a banner outside the museum’s façade, is a seamless visual transition between the adjacent Greek and Roman galleries and the temporary exhibition. The second-century Tunisian floor mosaic, predating the Byzantine era, depicts men carrying items to a feast, each wearing distinctly draped clothing. The men look as if they might walk out of the frame to meet similarly clothed Hellenic civilians and deities in the sculptures, vases and mosaics of the Greek and Roman galleries.

An Egyptian woman in a nearby painted shroud stands flanked by deities, recalling both the importance of patronage in Byzantium and the integration of Greco-Roman themes with localised symbols. An adjacent small-scale bronze bust of an African child, also from early Byzantine Egypt, cements the reach of African Byzantium, which included some Black Africans.

Pieces in conversation

The Tunisian mosaic commemorates Hellenic connections to North Africa. The Egyptian textile marks a cross-cultural and cross-temporal consideration. The bronze child denotes the integration of Hellenic and Nubian influences. The three pieces in conversation with one another illustrate the comprehensive peoples encompassed by this exhibition and the space-time it addresses.

Figuration dominates the exhibition’s galleries. Accented by text, geometric patterns, floral motifs and pottery, the painted and sculpted faces of Africa & Byzantium offer sympathetic connections. Legible expressions of devotion capture Christian faithfulness. Mythic, allegorical and religious figures rarely look out to their viewer, instead they direct their gaze up to the heavens or towards other individuals. Faces invite close looking while suggesting something beyond the frame, gazing through divine portals unseen.

The fluidity of language demonstrates the interconnectivity of cultures. The seventh-century Letter to the Superiors of the Monastery of Saint Paul the Anchorite is written in Coptic, the vernacular language of Egypt at the time, while Greek and Arabic at the top of the lengthy text call in God. This single object invokes the northern, southern and eastern shores of the Mediterranean, indicating how water, rather than land, traces the geographies of the objects on view. An impressive array of alphabets throughout the exhibition’s many manuscripts, captioned portraits, letters, bound texts, textual mosaics, inscribed textiles and other text-adorned objects catalogue an expanse of variety, rather than a wide spread of commonality.

A handful of notable objects embody this cross-cultural, trans-referential history encapsulated by the exhibition. The Egyptian Polyglot Psalter (12th-14th century) features six tight columns of text, differentiable by shifting alphabets. Ethiopic, Syriac, Coptic, Arabic, Armenian and Syriac again span a worn page opposite a geometric design. The text shows the importance of comparative study and the familiarity of monastic communities with multiple regional languages. The pattern decorating the page opposite the text, of pulsating Coptic crosses, mimics the ordered strokes of lettering, varying in tone, width and angularity.

Synagogue mosaics and lintels engraved with Hebrew sit beside folios from the Qur’an. The lintels’ inscriptions indicate they were donated by individuals connected to Egypt’s Muslim court. A fragment of a love spell written in Coptic and Greek establishes simultaneity of spiritual practices. An ivory box is carved both with the Egyptian goddess Isis and the Greek god Dionysus.

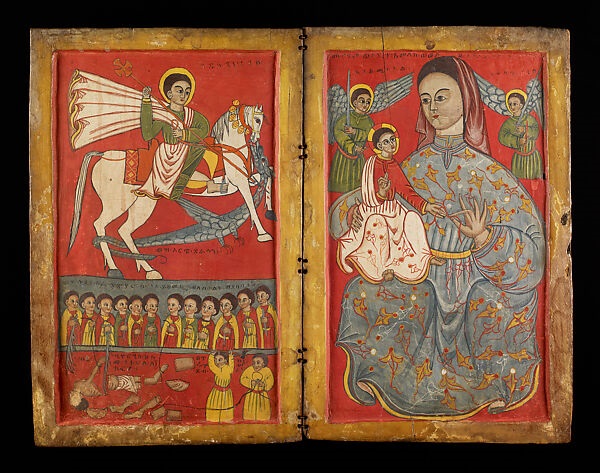

In the final rooms of the exhibition, Ethiopian Christian icons with characteristic wide eyes and draped in decadent fabrics stand apart from Nubian and North African Christian interpretations. The Diptych with Saint George and the Virgin and Child (late 15th-early 16th century) reflects the popularisation of the cult of the Virgin in Ethiopia by emperor Zara Yaqob.

African uniqueness

While the exhibition presents the integration of Byzantine motifs in North and East Africa in ways viewers might not expect, it does not as clearly distinguish the uniqueness of African methods. In much of Western scholarship, Medieval Ethiopian works were considered exceptional in their Africanity for their association with Mediterranean conventions. Accused of superiority over non-Christian African works but inferior to European icons, the contradiction denigrates Ethiopian artists as at once inauthentically African and insufficiently Christian. The exhibition might more aptly be called “Byzantium & Africa” for its omission of these concerns. Especially given the Met’s 2012 exhibition Byzantium and Islam: Age of Transition, it is a wonder why the 2023 exhibition reorders its title to fall out of line with its predecessor. Perhaps the answer is as simple as alphabetical order.

Especially given the lack of the Met’s African art collection during the Rockefeller Wing’s renovation, Africa & Byzantium does a lot of work for the museum. If the Met had an inclination towards self-critique, it would embrace the absurdity of this exhibition’s uniqueness. Egyptian, Classical, Medieval, African and Islamic art are divided across wings of the museum, but find home together in this exhibition, demonstrating often arbitrary separations but natural overlap. Stronger communication of the exhibition’s presentation of origins usually separated by the museum’s layout would serve its experience better.

The show is redeemed in its final gallery, which presents contemporary works by Tsedaye Makonnen, an Ethiopian American artist, and Theo Eshetu, an Ethiopian British artist. These works claim to present “the exhibition’s themes of memory and legacy” according to text inside the gallery, but memory and legacy of what? The contemporary works reimagine textiles and text, patterning and place. But they diverge from the rest of the exhibition by taking a strong stance about the violent disavowal of Ethiopians by those across the Mediterranean and the displacement of cultural and religious monuments, such as the ones seen throughout the exhibition. Makonnen and Eshetu assume the responsibility of addressing histories of imperial exploitation and extraction that overwhelm art and museum histories, a role often outsourced to contemporary artists of colour.

Overall, the exhibition provides an interesting and rare look at Byzantine rule and influence in parts of the African continent and an opportunity to view works held in collections around the world Egypt, England, France, Poland, Tunisia as well as collections across the US. The works are individually impressive and collectively marvelous.

*****

Source: The Art Newspaper

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price