From Samuel Tilden to Al Gore

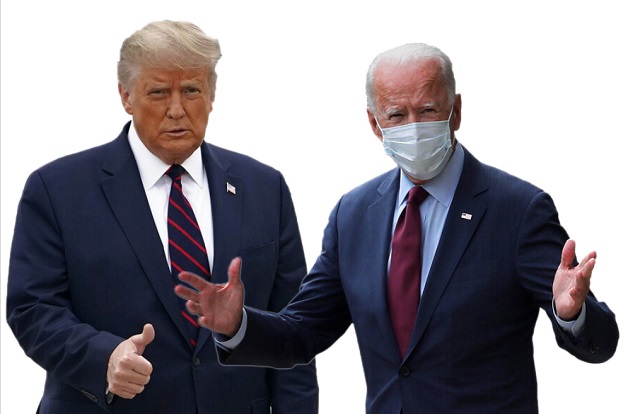

| ROBERT SPEEL | As states continued to count their ballots in the 2020 election, it seemed possible that Democrats and Republicans would end up in court over whether President Trump won a second term in the White House.

President Trump had said he’s going to contest the election results – going so far as to say that he believes the election will ultimately be decided by the Supreme Court. Meanwhile, Democratic presidential candidate Joe Biden has a team of lawyers lined up for a legal battle.

Unprecedented changes in voting procedures due to the coronavirus pandemic had created openings for candidates to cry foul. Republicans argued earlier this year that extending deadlines to receive and count ballots will lead to confusion and fraud, while Democrats said Republicans were actively working to disenfranchise voters.

The tussle between Trump and Biden isn’t the first time turmoil and claims of fraud dominated the days and weeks after the elections.

The elections of 1876, 1888, 1960 and 2000 were among the most contentious in American history. In each case, the losing candidate and party dealt with the disputed results differently.

1876: A compromise that came at a price

By 1876 – 11 years after the end of the Civil War – all the Confederate states had been readmitted to the Union, and Reconstruction was in full swing. The Republicans were strongest in the pro-Union areas of the North and African-American regions of the South, while Democratic support coalesced around southern whites and northern areas that had been less supportive of the Civil War. That year, Republicans nominated Ohio Gov. Rutherford B. Hayes, and Democrats chose New York Gov. Samuel Tilden.

But on Election Day, there was widespread voter intimidation against African-American Republican voters throughout the South. Three of those Southern states – Florida, Louisiana and South Carolina – had Republican-dominated election boards. In those three states, some initial results seemed to indicate Tilden victories. But due to widespread allegations of intimidation and fraud, the election boards invalidated enough votes to give the states – and their electoral votes – to Hayes. With the electoral votes from all three states, Hayes would win a 185-184 majority in the Electoral College.

Competing sets of election returns and electoral votes were sent to Congress to be counted in January 1877, so Congress voted to create a bipartisan commission of 15 members of Congress and Supreme Court justices to determine how to allocate the electors from the three disputed states. Seven commissioners were to be Republican, seven were to be Democrats, and there would be one independent, Justice David Davis of Illinois.

But in a political scheme that backfired, Davis was chosen by Democrats in the Illinois state legislature to serve in the U.S. Senate. (Senators weren’t chosen by voters until 1913.) They’d hoped to win his support on the electoral commission. Instead, Davis resigned from the commission and was replaced by Republican Justice Joseph Bradley, who proceeded to join an 8-7 Republican majority that awarded all the disputed electoral votes to Hayes.

Democrats decided not to argue with that final result due to the “Compromise of 1877,” in which Republicans, in return for getting Hayes in the White House, agreed to an end to Reconstruction and military occupation of the South.

Hayes had an ineffective, one-term presidency, while the compromise ended up destroying any semblance of African-American political clout in the South. For the next century, southern legislatures, free from northern supervision, would implement laws discriminating against blacks and restricting their ability to vote.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price