Nairobi, Kenya | AFP |

“The dream becomes reality”, “Our son, our hope”: the headlines in the Kenyan press in 2008 captured pride and excitement after the election of Barack Obama.

Eight years later, enthusiasm for the outgoing president has faded on a continent that he is accused of forsaking.

The election of the first black president of the United States on November 4, 2008 sparked scenes of jubilation in Kenya, the homeland of Obama’s father. A public holiday was declared in honour of his victory.

There were widespread hopes that Obama would do much for Africa, but as he prepares to hand over to either Hillary Clinton or Donald Trump, he is accused of neglecting the continent.

“Africa had unrealistic expectations towards Obama given his origins,” said Aly-Khan Satchu, a Kenyan economic analyst. “Especially during his first term, Obama was less involved in Africa” than his predecessor George W. Bush.

“People judged him very harshly during his first mandate because he didn’t do much for Africa,” said Liesl Louw Vaudran, an analyst at the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies think tank.

Satchu attributes this to the US recession and the need for Obama “to show the American public that he was the president of the USA”.

“During his second term, I think he tried to address this issue and he did more for Africa,” Satchu said.

Obama slow to engage

Obama was slow to engage in Africa, a continent far from the heart of US interests, preferring to make the Asia-Pacific region the centrepiece of his foreign and economic policy.

Unlike George W. Bush, whose PEPFAR programme has helped save the lives of millions of Africans with HIV/AIDS, Obama has launched no transformative initiatives on the continent. His 2013 “Power Africa” plan has fallen well short of its promise of doubling access to electricity in sub-Saharan Africa, generating just 400 megawatts (MW) of the 30,000 planned by 2030.

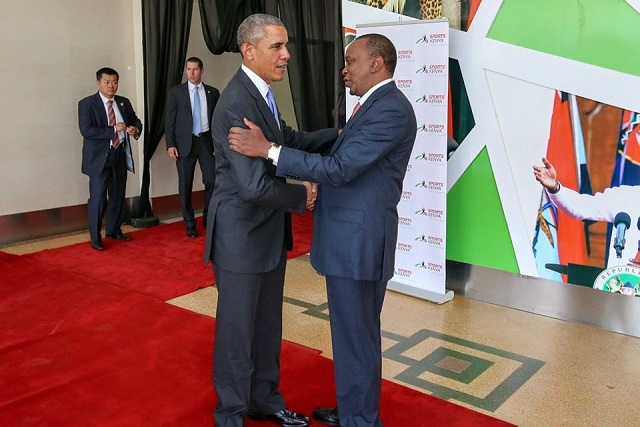

Obama’s African appearances have also been limited. There was a brief stopover in Ghana in 2009 — where he declared, “Africa doesn’t need strongmen, it needs strong institutions” — and then a tour of Senegal, South Africa and Tanzania in 2013, followed by a visit to Ethiopia and Kenya in 2015.

On each occasion he urged Africans to take their destiny into their own hands, and sought openings for US companies to invest in the continent.

He has moved to substitute a traditional aid-based policy with one of more equal trade-based partnership, with some success: African exports to the US, excluding oil, increased by nearly a half between 2009 and 2015.

Security and counter-terrorism remained a key priority for US efforts. Obama “expanded considerably the US military presence in Africa,” said Achille Mbembe of South Africa’s Wits Institute for Social and Economic Research. Nevertheless, success in the fight against jihadist groups such as the Shabaab in Somalia and Boko Haram in Nigeria has been elusive.

Similarly, efforts to foster democracy have faltered with a string of disputed or deficient elections and a growing trend among African leaders of clinging to power in defiance of constitutions.

‘Arrogant… racist’

African frustration with Obama has found resonance even in his own family, with half-brother Malik enthusiastically campaigning for Trump on Twitter, and even accepting an invitation to attend the final televised presidential debate in Las Vegas last month.

Malik’s position is not, however the norm, and many Africans readily denounce Trump’s views.

“Hillary Clinton, she is someone with a vision but this guy — how do you call him? — he is arrogant and a racist, he can be angry and even start more wars,” said Benjamin Namkobe, a 31-year-old motorcycle taxi driver in Nairobi.

Neither candidate has made much mention of Africa in their major speeches since being named their party’s candidate, but this is no surprise, said J. Peter Pham, director of the Africa Center at the Atlantic Council think tank in Washington.

“Africa largely does not figure into the electoral dynamics of the United States,” said Pham, adding that “foreign policy in general” takes a back seat.

He pointed out that US policy towards Africa “tends to enjoy bipartisan support”, meaning it does not represent a point of differentiation in debates.

It also means little change is to be expected, whoever wins.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price