The world is paying the price for not having responded adequately

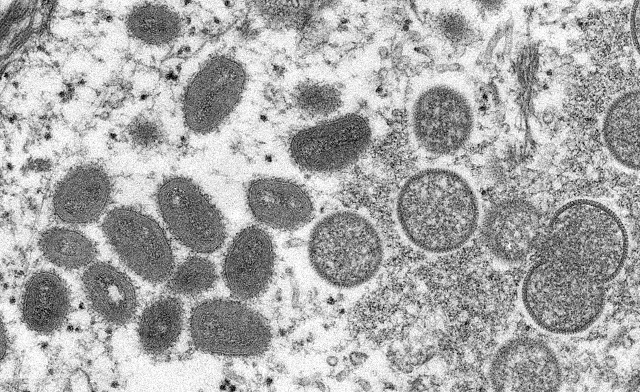

London, UK | Xinhua | Haunting Africa for years, monkeypox has finally drawn international concern, less than three months after cases exploded in countries such as Britain and the United States.

On Saturday, the World Health Organization (WHO) officially declared the current outbreak outside the traditional endemic areas in Africa as having already turned into a public health emergency of international concern.

In parts of Central and West Africa, monkeypox outbreaks have been occurring since the last century, and African epidemiologists have sounded the alarm, but were largely ignored.

Experts said monkeypox exposes the forgotten patients in areas such as Africa.

PAYING FOR NEGLECT

African researchers said they have long been warning of the potential for the monkeypox virus, which has been behaving in new ways, to spread more widely, the journal Nature said in a June article.

Since 1970, when monkeypox was first identified in humans, cases have been reported in 11 African countries, with most cases in the rural and rainforest regions of the Congo Basin.

Human cases have increasingly been reported from Central and West Africa.

Nigeria has experienced a large outbreak since 2017, with over 500 suspected cases, over 200 confirmed cases and a case fatality ratio of approximately 3 percent, and cases continue to be reported until today, according to the WHO.

It was only after 2017 that many African epidemiologists warned that the virus was spreading “in an unfamiliar way”: It was appearing in urban settings, and sometimes infected people who had genital lesions, suggesting that the virus might spread through sexual contact, the Nature article said.

“The world is paying the price for not having responded adequately” in 2017, as the virus proliferates in Western countries through what seems to be close contact with sexual partners, said Adesola Yinka-Ogunleye, an epidemiologist at the Nigeria Center for Disease Control.

“We as European nations and American nations have not really taken it seriously until now, when it has, of course, started to affect us,” Jason Mercer, a professor of virus cell biology at the University of Birmingham, who studies poxviruses at both the molecular and cell biology levels, told Xinhua.

“The reality is that monkeypox is a serious problem in African nations,” said Mercer, noting that over the last few decades, Africa has seen a massive increase in infections of zoonotic or human transmission.

AFRICA’S SHORTAGE OF MEDICAL RESOURCES

Europe’s rapid response to the recent outbreak stands in sharp contrast to the situation in Africa, where the disease has been spreading but vaccination rates are low and health systems remain weak.

“Vaccine inequality between Europe and Africa is very clearly happening again with monkeypox as is with COVID,” Mercer said.

Europe and America have vaccine stockpiles to deploy for slowing infection and reducing morbidity, but “in Africa these vaccines just simply aren’t available,” he said.

“There’s been a terrible inequity in vaccination rates,” as vaccine distribution and availability around the world are “incredibly unfair,” Martin Drewry, director of the London-based NGO Health Poverty Action, told Xinhua.

Besides vaccines, many parts of the world also lack strong functioning health systems to distribute them, Drewry said.

“You also need to have the systems to track and trace people who are infectious and respond quickly in those ways. And there are lots of reasons why the health systems are so weak,” he said.

“Unfortunately, the information shared with WHO by countries in West and Central Africa is still very scant,” said WHO Director General Tedros Adhanom Ghebreyesus on Thursday.

“This inability to characterize the epidemiological situation in that region represents a substantial challenge to designing interventions for controlling this historically neglected disease,” he added.

HEALTH INEQUALITY

The number of zoonotic outbreaks in Africa has risen by 63 percent in the decade from 2012 to 2022 compared to from 2001 to 2011, the WHO said.

Certain diseases in Africa, including monkeypox and Ebola, have gone largely unnoticed globally for many years, but as soon as they become a threat to the parts of the world with more resources and wealth, resources are suddenly mobilized to deal with them in those countries, said Drewry.

“Our biggest concern of all is that we will continue to allow health systems in some parts of the world to be so much stronger than they are in the areas where they’re almost non-existent,” he said.

Britain has 12,500 psychiatrists, while Sierra Leone has only two; in the United States, around 11,000 U.S. dollars are spent each year per person on healthcare, while the figure in Ethiopia is 67 dollars, Drewry noted.

Can Africa tackle these diseases on its own? Mercer asked. “The answer is probably not.”

European and American countries need to provide assistance in not only equipment, but surveillance, testing and diagnostics, making sure people are trained sufficiently to identify the disease, and reporting systems, vaccinations as well as antivirals are in place.

Helping underdeveloped countries also benefits developed ones themselves, Mercer said, just like in the COVID-19 pandemic, if populations without immunity are not vaccinated, European countries will end up with variants being re-imported.

“Are we being selfish with regard to vaccine distribution and tackling diseases in underdeveloped countries? In essence, yes,” he said.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Great