Concern as number of lions killed in the Queen Elizabeth National Park since 2018 rises to 17

SPECIAL FEATURE | On March 20, last year, six lions were found dead in the Ishasha Sector of Queen Elizabeth National Park located about 400km southwest of Kampala. This brought the number of lions killed in this park since 2018 to 17. Security agencies including Uganda’s national army, the UPDF, traced and arrested some of the killers. In May this year, Ronald Musoke visited Kazinga, a sparsely populated bushy village that hugs the southern part of this park in Kihihi sub-county, in an attempt to understand why lion killings are getting more frequent in this park.

Jackson Minezero, 78, a resident of Kazinga Lower Cell, in Kanungu District, lives on the edge of Queen Elizabeth National Park, one of Uganda’s most popular tourist destinations.

His homestead is only separated from the park by a 5ft-deep trench that runs several kilometres parallel to this village to prevent elephants, buffaloes and warthogs from crossing into human settlements.

Minezero represents what conservationists normally refer to as frontline communities—people who live closest to protected areas and occasionally experience deaths, debilitating injuries, and livelihood loss whenever wild animals attack.

Having lived here for 65 years, one would expect him to be a little more loathsome towards dangerous animals such as lions since he lives in their midst. But he says lions have never been his biggest headache; rather it is warthogs, buffaloes and elephants that often invade and wreak havoc in his garden and those of his neighbours.

“The lions are not bad ‘neighbours’ and they are not our biggest adversaries,” Gad Mbabazi, a local council chairperson of the nearby village, Kazinga Upper Cell, said.

When the six lions were killed last year, the authorities acted quickly. Both covert and armed government security operatives descended onto the park’s neighbouring villages in search of culprits.

According to a police report, the poachers entered the park, drove a herd of antelopes towards the pride of lions and when the lions hunted and killed the antelope, the poachers chased the cats away and laced the antelope carcass with poison.

When the lions later came back to feast on the carcass, they got poisoned and died. The poachers then mutilated the lion carcasses and harvested several body parts including paws, teeth and fats.

Minezero and Mbabazi were shocked at the news of the lion massacre. “People were surprised because lions are not our biggest adversaries,” Mbabazi said.

They told The Independent that the lions could have been killed for ritualistic practices. “We were told traditional medicine men are after lion products such as their fats,” Minezero added.

Apparently, local medicine men believe that Cataracts, an eye ailment locally known as Entale, can be healed by applying oil made from lion fats. Lions are also called ‘Entale’ in Rukiga— the dialect spoken in this part of southwestern Uganda.

The death of the lions in Queen Elizabeth Park shocked local conservationists and reverberated around the world just like an earlier incident in April 2018 when park rangers found 11 lion carcasses near Hamukungu fishing village in the northern frontier of this park.

Iconic species threatened

Across Africa, lions are one of the most iconic wildlife species that attract thousands of tourists to the parks. In Uganda, lions are mainly found in three of the country’s ten national parks; Kidepo Valley National Park in northeastern Uganda, Murchison Falls National Park in northwestern Uganda, and Queen Elizabeth National Park in southwestern Uganda.

The lions carry more significance in Uganda because it is a tourist attraction, especially to those who would like to see the Ishasha lions that have a rare gift of climbing trees.

“The lion represents Africa; it is an iconic species. People travel to Africa just to see lions. They generate revenue,” Stacey Sadelfeld, an American who has visited Queen Elizabeth National Park before, told The Independent in June this year.

An assessment done in 2006 by the Wildlife Conservation Society, a local conservation organization, found that each individual lion in Queen Elizabeth National Park generates about US$ 13,500 (Shs 52.65 million) per year for the national economy in terms of revenue. But lion numbers have been dwindling over the years due to numerous threats.

Escalating human-wildlife conflict

The road from Kihihi town in Kanungu District to the park’s gate at Ishasha is slowly getting busier following two years of COVID-19 inspired travel restrictions to the park. The road meanders through the small trading centre of Kazinga Upper Cell.

Residents, majority of whom are young men in their late teens and early 20s, are accustomed to looking on as big tourist vans sweep through their village from morning to evening, leaving behind brown plumes of dust.

Many youth here are semi-literate and they say they see little value in “Queen” as they refer to the park. Mbabazi, the Local Council-I Chairman of Kazinga Upper Cell says “his people” are not proud of conservation because they get far fewer benefits than the losses they incur in their crop farms.

Almost every homestead in this village is involved in subsistence farming. Most homes have coffee intercropped with bananas. There are also acres of maize, sorghum, rice, beans, cassava, bananas and many other staple crops. Some of these crops and livestock are also a favourite staple for the elephants, buffaloes, warthogs and lions. And this is where the conflict between the beasts in this park and the people living in their midst originates.

“People spend sleepless nights to guard their gardens to ensure that they harvest something. In most cases the villagers harvest nothing,” Brian Atuheirwe, 31, said.

Prossy Kyomugisha a young mother says people in her village suffer too much with the dangerous wild animals.

“Sometimes, the people who spend sleepless nights protecting their gardens get killed while others fall sick with malaria. Others get injured. That is why out of frustration when people find these animals, they sometimes kill them.”

Hassan Ali, 47, a resident of Kazinga Upper Cell says people in his village rarely get helped by the Uganda Wildlife Authority— the agency which is in charge of wildlife conservation in Uganda.

“When we call them (UWA rangers) for help, they instead switch off their phones. But when we try to chase or even hurt the wild animals that have escaped into our villages, they will descend onto our villages, hunt us like we have killed human beings,” Ali said, barely hiding his frustration.

“They prefer the wild animals to destroy our crops or even find us in our homes, kill us but if we retaliate by defending ourselves, they arrest and imprison us.”

Mbabazi added: “You cannot talk about compensation because this compensation is never equal to what people lose. “There are instances where people in these villages even lose their lives.”

The freshest incident in his mind happened in 2020 when his resident, Vincent Kasigaire, was gored to death by a buffalo that found him tending his garden.

“Usually if an animal kills a villager, UWA will take care of the funeral. They will also give the family about Shs 1 million (Approx.US$256) but this is not enough if you are to think about a lost life,” added Pafura Owakubariho, a boda boda (motorcycle taxi) rider in Kihihi town.

He said the people surrounding the parks should benefit “a little more” from Queen Elizabeth Park considering that they bear the biggest brunt when wild animals attack.

Similarly, Brian Atuheirwe who possesses a Diploma in Travel and Tourism from YMCA in Kampala said UWA rarely considers applicants from the frontline communities for such jobs.

“Very many are willing to apply but it is frustrating for the youth to see people who have never encountered these challenges get the jobs. That is why the people here don’t see conservation and tourism in a positive light. They look at tourism as an activity where white people come to visit and the government gets money. That is the tourism they know,” he said.

The Uganda Wildlife Act, 2019 compels the government to share 20% of annual revenues generated from tourist entry fees with communities that neighbour these parks. In the case of Queen Elizabeth National Park, the districts entitled to receive a share of the revenue are seven; Kanungu, Kasese, Rubirizi, Ibanda, Mitooma, Rukungiri and Kamwenge.

The revenue sharing programme is important in stimulating conservation-led economies within the districts neighbouring the parks and wildlife reserves. It is also supposed to nurture favourable conservation and attitude of communities living closest to the protected areas.

But youthful Atuheirwe told The Independent that the revenue sharing scheme rarely does what it is supposed to do. “I think they invest in wrong things,” he said. “They always buy goats for the communities but rarely do they tell people why they are giving them the goats. The people actually sell the goats even before they reach their homes.”

Gad Mbabazi, the Local Council Chairperson of Kazinga Upper Cell told The Independent that over the last four years, his village of about 140 households has got close to 160 goats bought using revenue given to Kanungu District Local Government.

But Mbabazi noted that considering the brunt his people face as a result of living next to Queen Elizabeth National Park, this is hardly enough.

Some conservationists The Independent has talked to say high poverty levels coupled with the lack of economic opportunity have contributed to the ever-growing tensions between the wild animals, the park authorities, and people who live in the midst of Queen Elizabeth National Park.

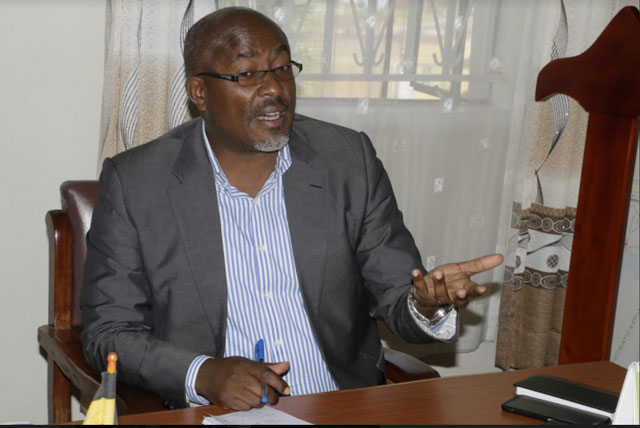

Sam Kajojo Arinaitwe, the LCV Chairman Kanungu District agrees. He told The Independent that Kanungu boasts two national parks ((Queen Elizabeth National Park and Bwindi Impenetrable Park) but when he crosschecks the revenues from the two parks and compares it with what trickles down to people who live closest to these two parks, he finds a big disparity.

In July, this year, Kanungu received about UShs 188,252, 400 (Approx.US$ 48,270) from UWA. This money is supposed to be shared amongst 12 villages that neighbour this park but it is usually not enough to do meaningful projects.

“We have not done enough as government to ensure that communities neighbouring the parks have better net benefits,” he told The Independent on May 31. Kajojo said what the communities living near this park are asking for is good responsiveness from park authorities.

Complex neighbourhood

However, Bashir Hangi, the UWA Communications Manager told The Independent on June 13 that unlike the other two protected areas in the country that are home to Uganda’s lion population, Queen Elizabeth Park appears to have unique challenges.

The park boasts three main water bodies; Lake George, Lake Edward and the Kazinga Channel which connects the two lakes. These lakes have six landing sites between them; Hamukungu, Kahendero, Katunguru and Kasenyi on Lake George and Katwe-Kabatoro and Kayanja on the Ugandan side of Lake Edward.

Over 20,000 people are said to depend on the fishing activity in Lake George and the Kazinga Channel and another estimated 15,000 depend on the Ugandan side of Lake Edward which straddles the Uganda-DR Congo border.

Residents of these fishing villages are mainly engaged in fishing and salt trade. They also keep domestic animals like cattle, sheep, goats, cats and dogs, and cultivate crops.

As such, there are usually higher chances of lions attacking cattle, attracting retaliatory killings of the cats. UWA’s reports from 2009-2017 point to more than 13,000 instances of human-wildlife conflict involving livestock predation by lions and leopards, and elephant crop damage among others.

Possible remedies

Hangi told The Independent that UWA intends to enhance its supervision by deploying some of the latest surveillance technology in the hotspot areas of this park.

Also, the national conservation organization shall continue to sensitize communities such as those in Kazinga village on the importance of protecting wildlife, he added.

However, in the twin villages of Kazinga, residents want immediate relief. Owakubariho says the trench that was recently dug by UWA and its partners should be sunk deeper than the 5ft considering that elephants have since devised means of crossing it.

He said an electric fence would be more efficient in warding off the dangerous wild animals. According to a statement emailed to The Independent on June 8 by Space for Giants, an international conservation organization, the electric fence can indeed ward off lion attacks. “Lions are, however, intelligent and will always test a fence for weaknesses,” Space for Giants said.

“Where fences have electrical faults and the fence is ‘off,’ it will allow lions to climb through. If the fence design is not effective for predators (there is a specific design for predators), then they will and can dig underneath the fence, so this needs to be taken into account in the design to prevent that.”

“Also lions climb trees and other objects, so it’s important that the fence is clear of any possible object or tree a lion can use to scale the fence. But if the fence design is specifically for predators, is well maintained and is in good working condition, it is very effective against lions.”

‘Predator-proof Bomas’

One other option that seems to be getting handy is the “predator-proof bomas” or kraals for livestock. Mike Schwartz, an American large carnivore researcher and consultant with the Uganda Carnivore Programme told The Independent that Queen Elizabeth Park has the unique challenge of having enclave communities within the park.

This, Schwartz said, has made human-lion conflict particularly challenging since livestock killing occurs fairly regularly and arguably more when compared with parks and reserves that are gazetted strictly for wildlife.

“When illegal grazing occurs, an uptick in lion attacks on livestock often follows. The consequence is anger by community members, who will then resort to poisoning,” he said.

Schwartz told The Independent that while traditional grazing methodologies are often used by community members to justify having a human presence in the park; the problem is that it is not necessarily compatible with lions and other large carnivore ecology.

He said it is erroneous to compare traditional grazing in this park with traditional grazing practices in other parts of East Africa, such as the Maasai and Samburu areas of Kenya and Tanzania.

Schwartz told The Independent that in the case of the Maasai and Samburu areas of Kenya and Tanzania who have a tendency to promote more traditional lifestyles that come with less of a carbon footprint, the situation is different in the case of the enclave communities of Queen Elizabeth National Park.

“The communities in this park tend to traditionally graze while also building larger houses, purchasing vehicles, and gaining access to other modern amenities that will only exacerbate the further carving up of the park with little room for large predators like lions,” he said.

“While there is certainly nothing wrong with wanting a better quality of life by way of more modern amenities, it simply is not compatible within a national park where large predators like lions have an ecological niche that includes large ungulates as a source of nutrition.”

Schwartz said his hope is that one day Queen Elizabeth National Park could serve as a model for cohabitation between humans and lions. But, changes to livestock value chains must be considered and implemented soon.

“Communities could, for instance, practice zero grazing,” he said. “We should also be looking at the conservancy models being used in countries like Kenya and Namibia, where communities essentially become custodians and caretakers of the park while benefiting from it through programmes such as payment for ecosystem services.”

Dr. Andrew Stein, a National Geographic Explorer who has been doing some work in southern Africa under the Conservancy Communities Living Among Wildlife Sustainability (CLAWS) project also told The Independent that determining the best course of action when wild animals come into community areas is important to understand the broader context. He said co-existence must be the goal for conservation agencies.

“Often communities feel left out and marginalized so the first step is to engage them to understand their challenges and fears. Once determined, it is important to work with the community to find solutions—not dictate them as outsiders.”

Meanwhile, Sam Kajojo, the head of Kanungu District Local Government says UWA should look for solutions in form of commercial projects that can directly create more economic impact for the communities that surround the park in the district.

“Community conservation goes hand in hand with mobilization of local women and men on how to tap into the tourism sector; handicrafts; creating for them a tourism centre where they can sell local products, where they can entertain visitors and also give information that tourists need is important because they feel part of the park.”

“We need to put up a Community Tourism Centre within Kihihi Sub-County to coordinate the other sub-counties of Nyanga and Nyamirama which could have the spill of these animals. We need to empower them economically by providing alternatives to poaching. Many of them are being killed inside the parks.”

Kajojo said there is also need to provide educational opportunities to the children who live in the proximity of Queen Elizabeth National Park.

****

This story was reported with support from Internews’ Earth Journalism Network

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price