Why good leadership at a national level is not enough to make a country successful economically

THE LAST WORD: Let us do a thought experiment. It is often said that the problem of Africa is poor leadership: if our continent had leaders dedicated to serving their people rather than lining their pockets, then our problems of poverty, conflict, misery etc. would end. Even the god of African elites, Barak Obama, made this claim in Addis Ababa when he last visited our continent. This slogan has been repeated so many times that it has acquired the status of divine truth.

Over the last 55 years Africa has seen 278 presidents. Yet most of our problems such as slow growth, corruption, tribalism, poor delivery of public goods and services etc. have demonstrated incredible resilience.

Only Botswana and Mauritius have escaped some of these problems. Africa has had some honest leaders who were genuine servants of their people – Julius Nyerere of Tanzania, Kenneth Kaunda of Zambia, and Leopold Senghor of Senegal. But their developmental record was much lower than that of Omar Bongo in Gabon and not fundamentally different from that of Mobutu Sese Seko in former Zaire, leaders considered the most venal in Africa.

I recently read a book by Sebastian Edwards titled Toxic Aid: the collapse and recovery of Tanzania. It is an insightful story of the economic disaster caused by Nyerere, perhaps the most sincere, public spirited, honest, humane and humble president in postcolonial Africa. But he destroyed Tanzania’s economy and brutally disrupted the social life of its people through his villagisation (Ujamaa) policy in an idealistic pursuit of a utopian dream of an egalitarian society. By the time he resigned in 1985, 45% of his nation’s GDP had disappeared. Tanzania had the second lowest per capita income in the world after Mozambique.

Contrast this with Robert Bates’ book, Beyond the Miracle of the Market: the political economy of agrarian development in Kenya. It is a story of how the state in Kenya under its founding President, Jomo Kenyatta, promoted agriculture policies that sustained impressive rates of growth and brought prosperity to many Kenyans.

Bates’ argument is that this success came, not from altruism, but through the self-interested decisions of the Kenyan agricultural elite (he calls them the “landed gentry”) to increase returns to agriculture. Yet Kenyatta was a tribalist and corrupt president who mostly lined the pockets of his fellow Kikuyu while also personally accumulating a large fortune for himself.

So we come to the development puzzle: why did the nationalist, sincere and honest Nyerere impoverish his fellow citizens while the tribalist and corrupt Kenyatta enriched his? It shows that good intentions are not enough. I am reminded of the statement by Adam Smith: “It is not from the benevolence of the butcher, the brewer or the baker that we get our dinner but from their regard of their own interest.” Smith’s contribution to capitalist ideology was to articulate a view that – holding other factors constant – the pursuit of self-interest in the market produces socially optimal outcomes.

Secondly, the development of a country is not only dependent on the decisions, actions and policies of its leaders and peoples, although the policies of Nyerere (ujamaa) and decisions (like throwing out IMF in 1979) did significantly contribute to the disaster. But development is also dependent of many other none domestic factors including decisions, policies and actions of neighbours. Leaders are facilitated and constrained by these factors.

For example, nations on the Pacific Rim (Hong Kong, Singapore, South Korea, Taiwan, Indonesia, Thailand and Malaysia) enjoyed unprecedented growth in the second half of the 20th Century. It is easy to attribute this to individual leaders- people like Lee Kuan Yew in Singapore. That is only partially correct.

The fundamental explanation may be that their geographical location near rapidly-industrialising post World War Two Japan provided positive spillover effects (like learning, copying and supplying) that facilitated what Albert Hirschman called “a multidimensional conspiracy in favour of development”.

Rwanda best illustrates this argument. In its 2014 World Competitiveness Report, the World Economic Forum produced an index on government efficiency measuring wastefulness of government spending, burden of regulation and transparency of policy making. Rwanda was number seven in the entire world. All the top ten countries have a per capita income at PPP of $54,000 and above, with the exception New Zeeland (number six at $36,000) and Malaysia (number eight with $28,000). Rwanda with a per capita income of $1,800 at PPP is the only poor country playing in the premier league of governmental efficiency.

It took Singapore 30 years to move from a third world country into a first world one with the third highest per capita income at $85,200. Will Rwanda attain first world status in 2024 (thirty years since the genocide) or in 2030 (thirty years since President Paul Kagame became president)? Based on past and present rate of per capita income growth, this is most unlikely. So why would Rwanda fail to achieve Singapore’s feat? Clearly the problem is not efficiency of government or paucity of leadership. There are domestic factors at play. But neighborhood is fundamental.

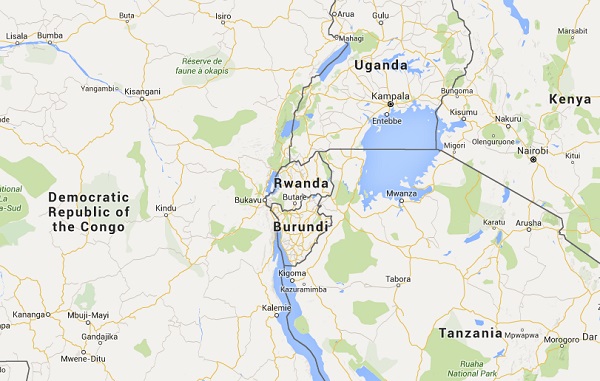

Rwanda is saddled with many regional problems. It neighbor to the south, Burundi, is unraveling fast; DRC to the West lives in a state of permanent crisis and may also soon unravel; Tanzania to the east is doing okay for now and Uganda to the north, like Tanzania, passes. Beyond these, Rwanda has Central Africa Republic, Kenya, South Sudan, Somalia and Zambia as distant neighbours. Rwanda’s growth is heavily reliant – not just on its domestic policies – but also on what is happening in these neighbouring countries.

President Paul Kagame can get things working in Rwanda but unless Uganda, Kenya, Tanzania or Congo build efficient rail and road transport and quicken the time of customs clearance in Dar es Salam, Mombasa and Matadi ports, Rwanda’s trade will suffer high time and financial costs in exporting and importing goods from abroad.

Secondly, for a country to improve its trade, it needs to first sell to neighbours, gain experience in market-share acquisition and then aggressively turn this knowledge to overseas markets. But if the economies of neighbours are not growing, Rwandan industry will be constrained in selling its goods in the region.

Its development is not entirely reliant on the decisions and policies of Kigali but also on the decisions and policies of Kampala, Nairobi, Dar Es Salam, Bujumbura and Kinshasa. Remember that while nations can choose their friends, they cannot choose their neighbours.

******

amwenda@independent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Mwenda, I think before even trying to thing of development let us what factors are required to develop a country like Uganda. Also what level of development ? We need to no were we are in terms of social economic propress. In all respect Africa can be blankly regarded as a failed continent, I have not objection to that nation, however I agree with any one who says that africa is more hopeful than ever. But let us not forget want Uganda was pre-colonial days, the days of kamurasi, kabaka chwa days and then contrast with today, what we have achieved. I dea of capitalism and it’s impact on our society and the subsequent repercussions, such as corruption, tribalism, manupulation of society . Even if we agree that we have reached some where to start the journey to development, we are still reminded by the ever existing threat to development” luck of rule of law” this issue is under rated, when it comes to development solutions, without the rule of law like most AFRICAN countries we are doomed. Knowledge, unity as a country, respect for life and then up hold the rule of law squarely.

In his article, “Beyond National Politics” published in his weekly column,

“The Last Word” of June 20, 2016, Andrew Mwenda attempted to compare

and contrast the Tanzanian economy and that of Kenya.

Viewing the economy as an aspect of the leadership, Mwenda wrote that

Tanzania suffered an economic disaster caused by Nyerere, “perhaps the most

sincere, public spirited, honest, humane and humble president in

postcolonial Africa. But he destroyed Tanzania’s economy and brutally

disrupted the social life of its people through his villagisation (Ujamaa)

policy in an idealistic pursuit of a utopian dream of an egalitarian

society. By the time he resigned in 1985, 45% of his nation’s GDP had

disappeared. Tanzania had the second lowest per capita income in the world

after Mozambique.”

This gloomy picture of Tanzania was contrasted with Kenya. About Kenya,

Mwenda argued that the state in Kenya under its founding President, Jomo

Kenyatta, promoted agriculture policies that sustained impressive rates of

growth and brought prosperity to many Kenyans.

He summed up his comparison with the question: “So we come to the

development puzzle: why did the nationalist, sincere and honest Nyerere

impoverish his fellow citizens while the tribalist and corrupt Kenyatta

enriched his? It shows that good intentions are not enough….”

To appreciate the difference between the Kenyan economy and that of

Tanzania, we need to look at both the economic history as well as the

respective strategies for colonising the two countries.

This is because whatever Kenyatta or Nyerere did was conditioned by what

happened in the past. Karl Marx once argued: “Men make their own history,

but they do not make it just as they please; they do not make it under

circumstances chosen by themselves, but under circumstances directly

encountered, given and transmitted from the past. ”

I cannot think of a better confirmation of what Karl Marx said than the

differences between the Tanzanian and Kenyan economies that Andrew

Mwenda is seeking to analyse. Let us go into the economic history of the two

countries.

In the very first place we must take into account the fact that Tanzania

(or Tanganyika as it was then known) was first colonised by Germany and

after Germany was defeated in the first World War, it became the

trusteeship territory of Britain.

This fact alone had serious economic consequences for the colony. It was

not until 1925 that the transfer of administration from Germany to Britain

was completed. During that period the economy suffered considerable

dislocation, something which never happened in Kenya.

The trusteeship status of Tanganyika had the effect of discouraging

investment in the colony. Investors tended to think the trusteeship was a

temporary thing and sooner or later Britain would be obliged to leave. This

created an atmosphere of uncertainty and investors were unwilling to risk

in such an environment.

The terms of the mandate meant to protect the local population prohibited

the separation of labour from land. By so doing the mandate was actually

going against proletarianisation in Tanganyika. Meanwhile the reverse was

happening in Kenya; there the proletariat was being created by fiat. The

people were being deprived of their land and being turned into wage workers.

Further, by the time Tanganyika came under British rule, the British empire

was already extremely large and Britain was getting very selective about

where it would invest. For this Tanganyika was not favourable at all.

Perhaps the most significant factor in establishing a vigorous capitalist

economy in Kenya was the fact that Kenya was a settler colony. At the same

time while Kenya was developed as a settler economy, something which

encouraged the imposition of relatively more advanced form of capitalism,

this was not the case in Tanzania.

A number of advantages flowed from Kenya’s being a settler economy. Perhaps

the most significant factor in establishing a vigorous capitalist economy

in Kenya was the fact that Kenya was a settler colony. one of the most

fundamental processes which acted to create a fairly well refined

capitalist economy was the act of dispossessing the natives of their land.

This had the effect of rendering them landless and therefore creating out

of them a proletariat i.e. a class which has no means of production and has

to sell its labour as the only means of earning a livelihood. this is the

class which provided labour for the capitalist farms and industry.

On the other hand Tanganyika settlers were not encouraged the way it was

done in Kenya. Land alienation was seriously discouraged.

It is also curious to note that two of Tanganyika’s early governors,

Cameron and Byatt made statements concerning what they viewed as the evil

effects of capitalism on African population. These statements sounded very

similar to what Nyerere was to argue later. The same administrators argued

that “capitalistic community” was to be depreciated.

And yet across the border in Kenya rabid capitalism with a proletariat and

all other aspects of capitalism was being created.

At independence therefore Kenya’s African bourgeoisie came into power to

strip capitalism of its racial character. It also moved to smash the *petit

bourgeois* (in the persons of Oginga Odinga and company) who were having

similar views as those of the ruling class in Tanzania.

The Kenyan bourgeoisie could do this because they had the material basis

to. It should be remembered that this process was further facilitated by

the funds which was made available for the African nascent bourgeoisie to

acquire the farms formerly owned by the settler bourgeoisie.

Through such programs the African bourgeoisie in Kenya had no choice but

to continue what had been happening in the colonial days albeit with a black

bourgeoisie. In any case that had been the strategy of decolonisation in Kenya

i.e. to ensure that nothing would be disturbed after independence.

This was not the case in Tanganyika. Over there the ruling class did not

have the material basis to do what its counterpart in Kenya was doing. In

stead, it moved to retard capitalist development by practicing some sort of

primitive socialism or ujaama as it was called.

_______________________________________________________________

Yoga Adhola is a former Editor-in-Chief of The People, newspaper of

UPC and a leading ideologue of UPC.

https://www.independent.co.ug/?p=6261