Missed opportunity

Kyagulanyi’s withdrawal means Ugandans will now never know how the justices of the Supreme Court would have ruled in the 2021 presidential election petition, especially in view of two famous presidential election annulments- in Kenya in 2017 and in Malawi in 2020.

Some legal analysts say the Ugandan Supreme Court was under pressure to prove whether it could make a bold move on jurisprudence and not just show that it is rigidly stuck in the principle of the substantiality test where it asks petitioners to prove the impact of their claims on an election.

The Ugandan judiciary however is overshadowed with the perception of harbouring ‘cadre judges’.

The famous court ruling in Kenya on September 1, 2017 annulling the election of President Uhuru Kenyatta in actual sense threw out the substantiality test which the Ugandan Supreme Court has based on to kick out past presidential election petitions. However for the court to arrive at the decision, a raft of judicial reforms had taken place in the country.

The reforms in the country’s new constitution adopted in 2010 made the chief justice the head of the Judicial Service Commission. In addition, the Kenyan judicial service commission constitutes a selection panel to appoint a new chief justice as it is currently doing to find a replacement for David Maraga who retired last month. In effect, the Kenyan president does not hover over the process.

In Malawi, the country went into new territory when the constitutional court annulled President Peter Mutharika’s win after tallying forms were tampered with among other irregularities. The judges delivered the ruling under heavy military escort. Mutharika was vying for a second term.

In Kenya, the judges called for fresh polls citing irregularities in “transmission of results”. The argument has been made by some that the judges in Kenya and Malawi were not all appointed by the sitting president which gave them leeway for acting independently. The lingering presidency of Museveni on the other hand has created proximity between the president and the Supreme Court that scholars and activists have argued does not portend well for the country’s constitutional and judicial processes.

In Uganda, the judicial service commission is headed by a judge appointed by the president. The commission nominates names to the president but still, President Museveni has a lot of sway on who becomes the next chief justice. That was the gist of the petition by lawyer Male Mabirizi asking Owiny Dollo to recuse himself from hearing the petition filed by Kyagulanyi.

As a result, the Ugandan judiciary is caught in a time warp. It is not just that all judges of the Supreme Court spanning a period of more than thirty years have been appointed by Museveni but a good number of them have served him as ministers and in other capacities as political appointees.

This is the reason some in the opposition felt Kyagulanyi’s election appeal to the Supreme Court was in vain. In contrast, the Kenyan judiciary is said to have gained a certain degree of autonomy since its judicial reforms. Even when relations had terribly soured between President Kenyatta and Chief Justice Maraga by the time the latter retired, few would disagree on whether it was not the result of changes that brought checks and balances in the country’s political and judicial system.

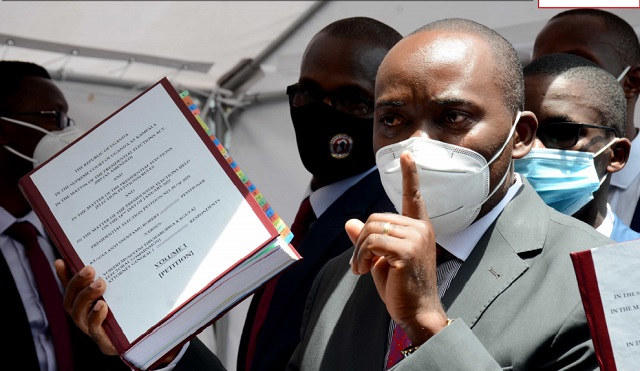

Kyagulanyi’s petition took another twist when four days after he announced his withdrawal, fellow former presidential candidate Willy Mayambala, wrote to the Supreme Court asking to inherit the collapsed petition. In a letter to the Supreme Court, Mayambala asked the court if it is possible to present new evidence.

Walubiri told The Independent that the court should reject any attempt for another candidate to inherit the petition because of the candidates’ different experiences. But some members of the Forum for Democratic Change (FDC) were quick with ‘we-told-you-so’ quips as soon as Kyagulanyi announced his withdrawal.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

This is utter rubbish. Courts of law are guided by law, and procedure, and not sentiments and feelings. Courts of law are not political institutions and judges aren’t politicians that act to please. They don’t base their decisions on public opinion, nor on lies and fake information. Walubiri is a very biased lawyer when he insinuates that its up to the Supreme Court to prove that it is not biased. It’s a known principal of law, and Walubiri should know better: IT IS TT THE ALLEGER TO PROVE. The burden of proof lies with those alleging. Walubiri, Kyagulanyi, and their likes must prove what they are alleging. Otherwise, defamation cases wouldn’t be on our law books. I thus find this story to have been written from an ignorant point of view, or the author is simply not rational.

There are a litany of categorical statements in your posts making worthless to even to attempt to rebut them. With deep respect, either you are incredibly naive or paid for this post.

True, Kyagulanyi went to Court to prove something, only to turn around, he has failed to prove anything hence the withdrawal!

We respect the judges

we only pray that it becomes easy to adjust to their opinion

To begin with how come one had a different opinion?

Then there is the preamble of the 1995 constitution, a litany of Uganda’s past

Finally summaries that contradict what we mere mortals observed

Forgive our ignorance, but these things have not only happened this year

it was quite confusing during the “togikwatako” deliberations

ah we hope to start understanding these things better [before the dementia phase], having witnessed all the happenings since 1966