Uganda study shows text messages can work

| ISABELLE COHEN | Every government needs money to fund its political, social and economic duties. Much of what they spend is generated from taxes, fines and sales of public goods and services.

The exchange of these revenues for government services is at the heart of the social contract citizens make with their governments. As the primary source of internal revenue, taxes play a key role in making growth sustainable and equitable. In most countries, tax payment is compulsory, and people who fail to comply are normally penalised.

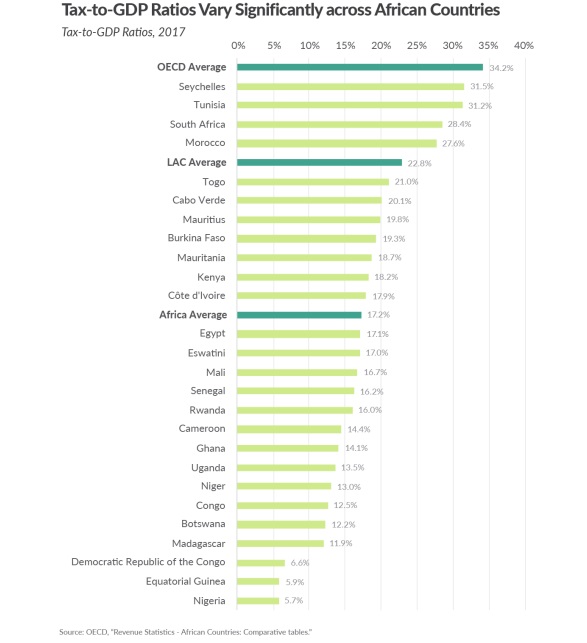

But the level of tax compliance remains quite low in a number of developing countries. A tax-to-GDP ratio compares a country’s tax collection to the size of its economy (GDP). The higher the ratio, the higher the proportion of money that goes into government coffers. At a tax-to-GDP ratio of 46.3%, Denmark is the World’s most efficient tax collector. In Africa, Tunisia topped the 2021 list with a ratio of 34.3% with Nigeria trailing at 6%.

In Uganda, low tax compliance contributes to a national tax-to-GDP ratio of 14%, well below the 18% average of the sub-Saharan African countries.

Although tax evasion happens in many spheres – and many types of people do it – close examination of tax returns filed to the Uganda Revenue Authority by self-employed individuals suggests rampant evasion. Those who own small businesses or are self-employed file taxes on their own behalf. For this group, the tension of whether to comply or not is particularly salient.

In practice, many such individuals in Uganda switch into and out of paying taxes. They may pay taxes in one year but not the next. And in keeping with what individuals report in household surveys, small business owners under-report their earnings to the Uganda Revenue Authority.

Though small business are, naturally, small, they can make an impact together. Reports suggest that micro, small and medium enterprises make up about 90% of production in the Ugandan economy, and employed over 2.5 million people as of 2014.

We recently conducted a study in Uganda to test the impact of tax payment reminders sent to respondents who were potentially liable to pay Uganda’s individual taxes. The reminders were sent to individuals in the form of text messages. Some messages focused on the rewards for payment, others on punishment for evading taxes.

The biggest finding of this experiment is that text messages can work. Receiving any text message increased the likelihood that an individual would pay their tax. The punishment-themed messages worked best, and the strongest response seemed to come from parts of the country which had recently seen the benefits of increased government revenue. The messages were also cost-effective: on average, they returned a sixfold benefit (on the cost) to the Uganda Revenue Authority.

The experiment

The experiment

A total of 98,000 individuals, all of whom had at some point paid taxes on revenue from a small business or other source, took part in the experiment. Specifically, these individuals had paid either Uganda’s presumptive tax or Uganda’s individual income tax. Most had paid the presumptive tax, which is charged on businesses with annual sales of between Shs10 million (US$2,800) and Shs50 million (US$42,000).

Small business owners are responsible for keeping their own financial records. If they fail to pay taxes, they personally suffer consequences, such as penalties or business closure. And because the businesses are small – and generally have fewer than 25 employees – no tax is paid on behalf of any employees.

With this experiment, the Uganda Revenue Authority set out to understand more broadly how different message content affected Ugandan taxpayers. The respondents were sent different messages on 28 June 2019, just before the end of the 2018/19 financial year.

The first quarter received a general “pay-your-tax” reminder message: “Dear esteemed client, please file your income tax return and pay the tax due by June 30, 2019.”

Another quarter received a message explaining how tax funds are used to benefit Uganda: “Dear esteemed client, by paying your taxes you make it possible to educate our children, fund our healthcare, and keep us safe.”

The third quarter received a message explaining the punishments for failing to pay taxes: “Dear esteemed client, file your income tax return and pay the tax to avoid unnecessary payment of interest, penalties, and possible enforcement actions like the closure of business.”

The fourth quarter was reserved as a control group, and did not receive a message.

Before the messages were sent, payment rates were the same across the four groups. After the messages were sent out, individuals who received a general reminder and the group that received punishment-themed texts began to repay at higher rates than those in the other groups.

All three text messages were most effective in remote areas where schools, police posts or local courts had recently been built. In other words, the people who responded most to the texts lived in places with (until recently) worse than average social amenities. The response was even better where there had recently been efforts made by the Ugandan government to improve the quality of these services.

A punishment-focused text to business owners across Uganda returned a 13-fold benefit on cost to the Uganda Revenue Authority.

Over the next months, the differences between the groups persisted, driven particularly by results among small business owners. We estimate that just by sending these simple text messages, the Uganda Revenue Authority raised roughly an additional US$18,000 (Shs64.8 million) in tax revenue in the fiscal year ending 30 June 2019.

Takeaways

The first main conclusion of the study is that for the average individual paying these taxes, the reminder highlighting punishment for noncompliance is more effective than those focusing on benefits. Tax agencies like Uganda Revenue Authority may want to be careful about the kinds of messages being sent to taxpayers.

The second main conclusion is that what people see around them affects how they respond to tax messages. Individuals who have seen public goods in practice – for whom the government has recently increased the availability of public services – respond more strongly to the text messages.

These findings suggest that improving service delivery may be (partly) its own reward. This is especially so if it makes some individuals view the government more favourably, and become more likely to pay their taxes.

Some issues still need further study. For example, we cannot say much yet about the long-term effects of these text messages, or how what people know about taxation affects their response to these messages.

****

Isabelle Cohen is Assistant Professor at the Evans School of Public Policy, University of Washington.

Nicholas Musoke, a Research and Policy Analyst at Uganda Revenue Authority, contributed in this article. The views and opinions are those of the authors, and do not necessarily reflect the official policy or position of any part of the Ugandan government.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price