To increase emerging markets’ share of infrastructure investment, the world needs more `patient capital’

COMMENT | JUSTIN YIFU, HAVARD HALLAND & YAN WANG | Lawmakers in the United States have introduced legislation that, if enacted, would create a new development finance institution (DFI) to replace the Overseas Private Investment Corporation. Unlike its predecessor, the new agency would be able to make equity investments, a reform that reflects growing global recognition that ownership stakes are an essential component of sustainable-development financing.

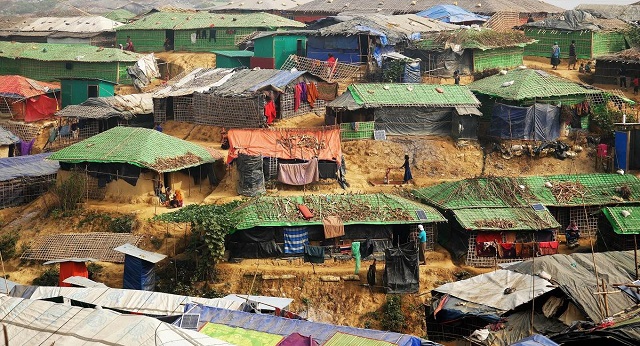

But, however important, this shift in development finance, in the U.S. and elsewhere, will not solve one of the major challenges facing the Global South: a dearth of infrastructure investment. To address that shortcoming, an entirely new approach may be needed.

To achieve the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), the world’s multilateral development banks (MDBs) and their private-sector branches, the DFIs, have committed to increasing private-sector finance by as much as 35% over the next three years. To support infrastructure investment, MDBs have expanded their offers of risk-mitigation instruments for private investors, along with other important measures. Yet they have made only limited investments in infrastructure equity, focusing such investment, instead, on small- and medium-size enterprises in emerging markets.

Why shouldn’t infrastructure equity be left to the private sector? Although infrastructure assets have the advantage of providing steady, long-term income streams, the early stages of most big projects carry higher levels of risk. When projects are over budget, fall behind schedule, or fail to generate projected returns, investors pay the price. So, rather than investing in new projects, private investors tend to prefer to channel their money toward operational infrastructure that is already generating stable revenue.

Reflecting this aversion to risk, the total number of shovel-ready projects worldwide has held steady in recent years, even though investor interest in infrastructure investment has soared, causing deal values to increase. Moreover, in recent decades more than 70% of private-sector investment in infrastructure has been channeled to advanced economies, according to McKinsey.

To increase their impact, MDBs and DFIs need to direct far more capital toward infrastructure projects in the preparation and construction stages, when the private sector invests less. While loans and risk-mitigation instruments are necessary to support this effort, they are not sufficient, because they are generally provided after a project is fully documented and confirmed as “bankable.”

Equity investors, by contrast, frequently play a central role in the early stages of a project: the initial technical and financial structuring phase. If equity investment is lacking, potentially profitable projects may never reach the “bankable” stage at which debt financing and risk mitigation can be confirmed. Yet, because equity investors are the last to be repaid in case of project failure, they carry the most risk.

To increase emerging markets’ share of infrastructure investment, the world needs more “patient capital” from equity investors willing to take those early risks and wait longer for their investments to mature. If the private sector won’t fill this void, then the onus is on MDBs and DFIs, which, by definition, exist for this purpose.

Although some MDB and DFI financing is available for early-stage infrastructure investment – including from China’s Silk Road Fund, the World Bank, and the International Finance Corporation – the supply of such financing is dwarfed by demand. MDBs and DFIs could rapidly increase their contribution by channeling part of their capital through public financial institutions that already undertake this type of investment.

Strategic investment funds may hold the answer. These funds, which are wholly or partly owned by governments or other public institutions, invest according to a “double bottom line,” which measures performance by financial success and by social and environmental impact. In the last decade, nearly three dozen strategic investment funds have been established around the world in economies as diverse as India, Ireland, the Philippines, and Senegal.

These investment funds are equity investors that operate as intermediaries between the private and public sectors, often independently, but adhering to a government-defined mandate. Staffed primarily by private-sector professionals, many have achieved high levels of private-sector co-investment, thereby expanding the pool of capital available for infrastructure investment. For example, in October 2017, India’s National Investment and Infrastructure Fund announced a $1 billion deal with a unit of the Abu Dhabi Investment Authority, one of the world’s largest sovereign wealth funds. The agreement will help India finance critical infrastructure upgrades.

As holders of public capital, MDBs and DFIs can convert assets into “patient equity” by deploying capital through well-performing strategic investment funds. They can provide loans to help governments capitalize their strategic investment funds, capitalize the funds directly, or co-invest at the project level. By directing capital to the strongest performers, each entity could promote integrity and encourage competition. Although some DFIs, including the Asian Development Bank and the European Investment Bank, are already engaging with strategic investment funds, there remains considerable room for growth.

MDBs and DFIs have rightly increased their efforts to mobilise private capital. A shift toward early-stage equity investment in infrastructure, and engagement with strategic investment funds, could significantly strengthen their capacity on this front, and increase the likelihood of the world achieving the SDGs.

*****

Justin Yifu Lin, former Chief Economist of the World Bank, is Director of the Center for New Structural Economics, Dean of the Institute of South-South Cooperation and Development, and Honorary Dean at the National School of Development, Peking University. Håvard Halland is a visiting scholar at the Stanford Global Projects Center (GPC) at Stanford University. Yan Wang is a senior fellow at the Center for New Structural Economics, Peking University.

Copyright: Project Syndicate, 2018.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price