How failure to share family cultural history endangers symbols that represent common ancestral origin

COMMENT | NATHAN KIWERE | Writing on page 137 of his book, ‘The Baganda’ (Macmillan and Co., 1911), John Roscoe, a British colonial historian, states that when animals were becoming scarce, Kintu, with the general consent of his people, made the rule that certain kinds of animals should be taboo to certain families. Thus, those particular species of animals were left to other families, and the animals were given a better chance of multiplying than if every man had been free to hunt every species for food. Each family abstained from that particular kind of animal of which they had partaken with ill results, and that animal was tabooed by them, and it became their totem. This historic incident is believed to have happened between 1200 and 1230 AD. Considering the weight and significance of this decision by Kintu; the mythical father of all Baganda and company at that material time and its resonance with the much-hyped nature conservation advocacy today, we must all agree that the architects of this tradition were inspired by nothing short of a stroke of genius. And, in my opinion, this should be documented as one of the greatest wonders of intangible cultural heritage.

In the Ugandan context, a totem is a symbol that represents a group of people with a common ancestral origin known as a clan. Several clans constitute an ethnic group. Traditions surrounding the totems are among the most important cultural practices in Uganda. This cultural heritage plays a significant role in the knowledge of their genealogies, naming rites, marriage practices, and choice of food, among others. This sacred totemic practice has typified their cultural wellbeing from their traceable beginning, hundreds of years ago. It has continued unabated throughout the ages, in spite of the social, political, economic and, more recently, technological transformations that have adversely affected established cultural institutions across the globe. To this day, totems remain among the few remnants of indigenous knowledge heritage that remain firmly rooted in the social fabric of Uganda.

The bushbuck (engabi) is among the most populous species in Murchison Falls National Park. The park is located in the districts of Bulisa, Masindi and Kiryandongo, all part of the greater Bunyoro-Kitara kingdom. It does not take rocket science to understand why the bushbucks enjoy an unwavering majority in the park. In a recent interview, the Prime Minister of Bunyoro Kingdom; Norman Lukumu, told this writer that the bushbuck commands the largest following among the totems of the Banyoro indigenous communities. It has been for more than half a millennium the dominant symbol among these people and for this reason, the bushbucks have multiplied over the years without danger of interference from man. A visit to Murchison Fall National Park will immediately prove this as herds of this animal can be seen in virtually every nook and cranny of the massive park.

Kintu’s ingenious far-sightedness at the time when the population was not only very small compared to these days but also animals were much more plentiful cannot go unsung. Close to a millennium later, this tradition is still holding on, albeit in a wobbly manner. As the pillars of our cultural heritage continue to bear indelible cracks, totems remain among the few elements buttressing what remains.

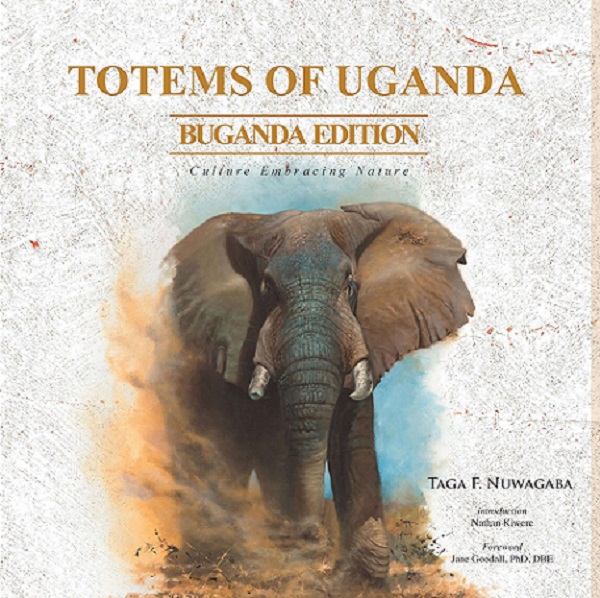

Unfortunately, even this pillar is under threat of giving way, if the happenings of the time are anything to go by. That this hitherto entrenched tradition is under threat of extinction as the levels of ignorance about totems by their ostensibly ardent practitioners rises is worrying – to say the least. This observation came true several years back while Taga Nuwagaba, a Ugandan artist and author of ‘Totems of Uganda: Buganda Edition’ was traveling to Masaka in a taxi on the Kampala-Masaka highway.

The driver of the taxi spotted a squirrel-like creature tottering about in the middle of the tarmac. The driver, whose name was Ssengendo, deliberately trailed the creature and run over it, crashing it to instant death. One of the people who observed him performing the gruesome act was the conductor. He asked him what he had killed this time round, implying he derived pleasure in habitually running over such creatures on the road. He responded that it was just a mere thing, nothing valuable, until a gentleman seated in the front seat corrected him that it was actually a civet (ffumbe), which turned out to be Ssengendo’s totem.

The driver was previously known to be an avowed man of the Kabaka and custodian of culture and yet it shockingly turned out he did not know what his totem looked like. Out of shame and devastating distress, Ssengendo could not proceed with the journey; he handed over the vehicle to the conductor to take on the rest of it as he took time off to “mourn” the sacrilegious act he had just performed.

It turns out Ssengendo is not alone in this enterprise; countless Ugandans are disconnected from their totems and some don’t even know their names. The younger people see them as old-fashioned shibboleths that belong in the past, or, at best, in the museums. This precedent is engendered by the fact that the older generation has played a dismal role in passing on important information about culture at family level. Totems as vectors of nature conservation have no meaning unless people know what their totems actually look like. Ugandans have to do more to restore this cultural glory and teach the world this alternative means of culture embracing nature.

*****

Nathan Kiwere is the executive director of Kakakuona Foundation

www.kakakuona.org

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price