In East Asia, corruption `oils the wheels’ of business and governance, in Africa it `rusts the wheels’

COMMENT | CHRISTOPHER BURKE | Corruption is a global issue shaped by cultural, economic and political contexts that manifest differently across regions closely associated with development. East Asia and Africa both grapple with corruption, but the nature, scale and consequences differ significantly. Examining these differences provides insights into their impact on development and potential paths for change.

In many East Asian countries, corruption “oils the wheels” of business and governance. This does not imply that corruption is acceptable, but that it is integrated into systems in ways that minimise disruption to progress. Officials or intermediaries may take a percentage of the allocated funds, but ensure the completion of projects or services to a satisfactory standard. The rationale is pragmatic: if the work meets expectations, scrutiny is minimal and opportunities for further projects and investments continue.

Corruption takes the form of kickbacks or “gifts” and is regarded as a cost of doing business. Infrastructure projects from high-speed railways and urban developments to energy plants are completed with remarkable efficiency. This paradoxical system; combining low-level corruption with high productivity, minimises discernible damage to economic growth.

In Africa, corruption “rusts the wheels”, undermining development and leaving projects incomplete. It is not a systemic problem, but an endemic feature of governance and business. Officials or contractors frequently take a disproportionate share of funds—often exceeding 50 percent—leaving insufficient resources to finish projects or deliver quality services. Unlike East Asia, where some level of productivity accompanies these irregular practices, corruption in Africa frequently results in dysfunctional healthcare facilities and ghost schools. Poor roads and abandoned energy projects are less conducive to growth. The disparity highlights a critical lesson—it is better to “eat” 10 percent of $1 million than 50 percent of $1,000. The former leaves sufficient funds to complete a project, while the latter renders the entire effort futile.

The contrasting approaches to corruption in East Asia and Africa affect economic development. East Asia’s practice of “eating a little and ensuring completion” sustains a cycle of growth. Governments and private entities are incentivised to maintain quality to secure future contracts and investments. South Korea achieved rapid industrialisation despite periods of significant corruption in its early development stages.

The endemic nature of corruption in Africa compounds these issues. According to a 2023 Transparency International report, many African countries rank among the lowest in the Corruption Perceptions Index. Widespread mismanagement and embezzlement erode public trust and undermine sustainable development.

Cultural and structural factors influencing corruption differ significantly between East Asia and Africa. Confucian traditions in East Asia emphasise collective progress, hierarchy and accountability within informal networks. Corruption exists, but beneficiaries face implicit expectations ensuring results to maintain their social standing and secure future opportunities.

Cultural dynamics in Africa further exacerbate corruption. In many environments, individuals who refrain from exploiting opportunities for personal gain may be considered naive or foolish. Public officials adhering to integrity can face ridicule or ostracism from communities expecting them to share the spoils of their position. This cultural pressure perpetuates a cycle where immediate personal rewards outweigh long-term collective benefits.

The legacy of colonialism, weak institutions and patronage systems where political loyalty often takes precedence over meritocracy has entrenched corruption as a survival mechanism in Africa. Leaders and officials divert resources to sustain loyalty among their networks, prioritising immediate benefits over long-term outcomes. The informal nature of many African economies further complicates accountability as transactions often occur outside regulatory frameworks.

While corruption undermines development in many African countries, change is possible. The average life expectancy in Africa has increased from 36 years in 1950 to 65 years today. With people living nearly twice as long, the incentive to prioritise immediate consumption over long-term planning diminishes, as individuals and institutions must now prepare for futures that extend decades beyond previous expectations.

Africa’s growing economies present opportunities to shift the dynamic. As projects and markets expand, the benefits of completing high-quality work will increasingly outweigh the short-term gains of excessive corruption. As these economies grow, they demand higher standards of accountability and efficiency, reducing opportunities for unchecked corruption. With increased opportunities for trade and investment, governments and businesses face greater pressure to deliver results.

Africa can draw valuable lessons from East Asia’s experience. The key is to balance pragmatism with reform. While eliminating corruption entirely may be unrealistic in the short term, prioritising project completion and fostering a culture of accountability can mitigate its negative effects. Investments in robust institutions, transparent procurement processes and civic engagement are critical to this transformation.

Botswana and Mauritius provide examples of how good governance and anti-corruption measures can coexist with growth. Both have invested in strong institutions and policies that reward efficiency and transparency, serving as models for the continent.

The comparison between corruption in East Asia and Africa underscores stark differences in practice and impact on development. Africa is not destined to remain trapped in a cycle of corruption. By prioritising accountability, innovation and structural reforms, the continent can drive its own path to sustainable development.

****

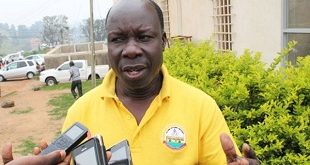

Christopher Burke is a senior advisor at WMC Africa, a communications and advisory agency located in Kampala, Uganda. With nearly 30 years of experience, he has worked extensively on social, political and economic development issues focused on governance, communications, international relations, conflict mediation and peace-building in Asia and Africa.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price