When paranoia for controversy clashes with financial ambition

Kampala, Uganda | DOMINIC MUWANGUZI | In 2010 the first edition of the Controversial Art Exhibition was mounted at Afriart gallery, Kampala. It was a brainchild of the art gallery, under the patronage of Kampala Arts Trust, a creative collective of visual and performance art practitioners living and working in public and private spaces within the precincts of Kampala.

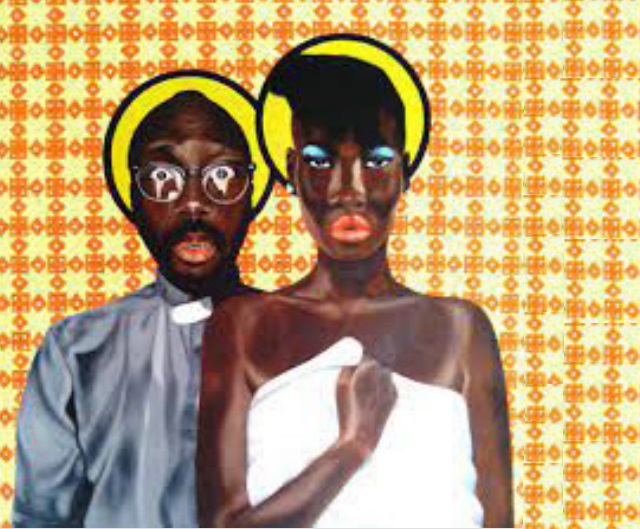

The exhibition invited artists to create art which provokes controversy through controversial topics and use of non- traditional media and techniques. The first edition featured ten artists who immediately focused on sex and nudity.

The second edition 2011 was more democratised in terms of subject matter and material used. It saw artists like Collin Sekajugo, Eria Sane Nsubuga, Mzili, Lilian Nabulime, Jude Kateete and Edison Mugalu examine a diversity of themes like homosexuality and sexual freedom, but also democracy and freedom of expression, recycling, and womanhood and fertility.

It was obvious the artists had been given the right platform to express their wealth of ideas. Before, exhibitions around Kampala were mainly dominated by vibrant and energetic imagery of wild vegetation and animals prowling the dry savannah. This was because of the demand dictated by the gallery clientele who were random white expatriates and a bevy of tourists.

The Controversial Art Exhibition was a novel experience that did not pose any restrictions on the creativity of the artists. This probably was so because the project was funded by Dutch Embassy in Kampala which afforded the artists relative comfort to create art without thinking primarily to make profit out of the exercise.

But without making money- the art was not for sale at the Exhibition- how were artists going to survive after?

It is certain that after the exhibition, several artists returned to their routine of producing art to make profits. Their objective to participate in the art project was to have access to the money made available by the funders, and not to be part of its wider vision and objective.

This perhaps could have been one of the reasons why the annual Exhibition, which had been billed to become a permanent fixture on the local art calendar, folded in its second year. However, one could rightly argue that at least it left an indelible impact on the local art scene which can be witnessed today with the approach on technique and medium by a certain group of artists.

The exhibition highlighted more than the notion of external art funding and its problematic consequences on many artists who work primarily to survive by the day into perspective. It seems certain that external art funding since time immemorial is an incompatible tool to “aid” and sustain the creative practice of local artists. It indeed also raised questions on issues of originality, authenticity and relevance of art created for the exhibition viz a viz the public reaction to it. Did the art create critical conversations and reflections as suggested by Exhibition curator Henry Mzili Mujunga?

The exhibition highlighted more than the notion of external art funding and its problematic consequences on many artists who work primarily to survive by the day into perspective. It seems certain that external art funding since time immemorial is an incompatible tool to “aid” and sustain the creative practice of local artists. It indeed also raised questions on issues of originality, authenticity and relevance of art created for the exhibition viz a viz the public reaction to it. Did the art create critical conversations and reflections as suggested by Exhibition curator Henry Mzili Mujunga?

Mujunga wrote the following in the first curatorial statement: “As a responsible citizen, the artist should be courageous enough to portray society in ways that might be unpleasant and which mighty even have dire consequences on his or her personal safety. After all, the artist is a high priest who communes with the gods to plan the next step for humanity.”

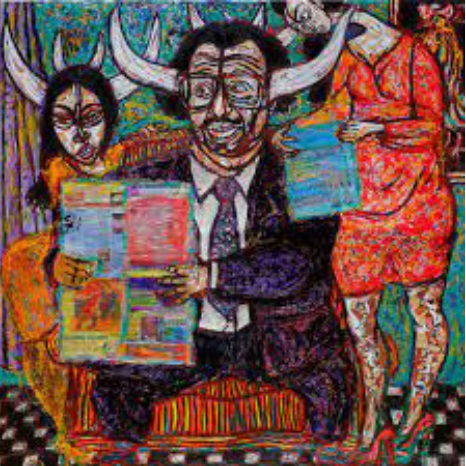

So how courageous were the participating artists in the two exhibitions? This question can suitably be answered by citing specific works in both exhibitions which ‘portray society in ways that might be unpleasant and which might even have dire consequences on the artist’s personal safety’.

Eria Sane Nsubuga’s Mentor and Protégé 2010 in the first edition of the exhibition was a brilliant composition. The caricature painting portraying two familiar political figures: Adolph Hitler of Germany and Mahmoud Ahmadinejad of Iran, suggested the theme of controversy in the artwork. Both political figures are known for their controversial stance; especially on the subject of peace and democracy. In the painting, the artist insinuates that Adolf Hitler is a mentor- of course because he belongs to a different generation of repressive leaders- to Ahmadinejad who is a recent political character courting international criticism for promoting his country’s nuclear project. This figurative representation, suggested the boldness by the political satirist to probe a delicate topic of political inequalities that dominate the globe. Additionally, Sane’s technique of exposing the characters nudity evoked the European classical art technique where nudity was a symbol of political evil. However the artist chose to cover the genitals of the two characters with imagery of nuclear- rocket bombs.

If Sane and a few of his colleagues where successful in drawing the attention of their audiences to their art and stimulating their reflections on subject matter and technique, then this underscored the reason why the exhibition was organised.

In contrast to Sane’s courageous tackling of political themes in his work, some artist chose to play it safe by working on themes which were less controversial or deliberately took on an ambiguous stance.

It was typical of Ugandan artist who have paranoia for controversy. This is primarily because of the social- cultural setting within which they are bred. This society dictates submissiveness and politeness on even issues that should invite blatant criticism. Such artists misinterpret controversy as being confrontation; something that could turn away their “good customers”.

The question, of course, is why such artists take part in an exhibition which calls for breaking of norm?

As suggested earlier, this was their deliberate move to benefit from the available funds from the cultural funder. There was less interest to assume the identity of the ‘high priest who communes with the gods to plan the next step for humanity’. This is where the real controversy for the Controversial Art Exhibition lay.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price