Experts say Uganda’s involvement inflames tensions

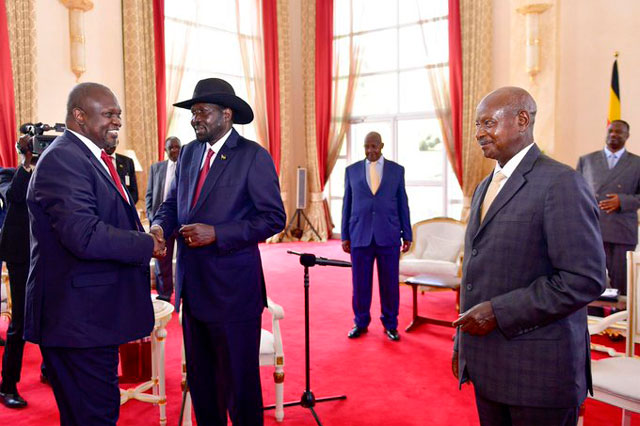

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT REPORTERS & AGENCIES | The entry of soldiers of the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Forces (UPDF) into South Sudan in support of the government of President Salva Kiir Mayardit has inflamed tensions there. That is according to expert observers, civil society activists, and opposition politicians.

In a major anti-UPDF development, the SPLM/A-IO of First Vice President, Riek Machar, has announced it has withdrawn its participation in several joint government activities to protest the presence of the UPDF.

“The invitation and the presence of Uganda Peoples’ Defense Forces (UPDF) in the country depicts a mens rea (intention) and preparation for war,” said the SPLM/A-IO in a March 17 statement. It said the UPDF deployment around the country complicates the geopolitical situation of South Sudan.

“It is tantamount to a Declaration of War on the peace partners and the people of South Sudan by the two governments,” the statement said.

Oyet Nathaniel Pierino, the Deputy Chairman and Deputy Commander-In-Chief of the opposition outfit who is also the First Deputy Speaker of the National Legislature, said they were protesting three infringements: the continued illegal detention of their ranking members, the deployment of Ugandan troops in South Sudan, and ethnic profiling of the Nuer community.

The Machar group announced it was immediately stopping its participation in the Joint Defense Board (JDB), High-Level Political Committee (HLPC), Joint Military Ceasefire Committee (JMCC), and Joint Transitional Security Committee (JTSC).

Edmund Yakani, a South Sudanese civil society activist told journalists that President Kiir and First Vice President Machar bear the primary responsibility to stop the violence immediately and should both be held accountable for the ongoing conflict.

“While Uganda is one of the IGAD peace guarantors, it is effectively engaged with its forces in violating the spirit of the peace process,” he said. According to him, President Yoweri Museveni should instead be helping prevent South Sudan from sliding into war.

Gen. Kainerugaba’s warning

Yakani was speaking after airplanes of the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) and the Uganda Peoples’ Defence Force (UPDF) on March 19 bombed the Upper Nile State town of Nasir for the second time. The attack reportedly wounded two people, a mother and her two-year-old child.

“The market has been burned down, and I went there to confirm it myself. I don’t know how many shops, but most of them have been destroyed,” Nasir County Commissioner Gatluak Lew Thiep said, according to media reports.

“Four bombs targeted my compound as commissioner. That was the second round, and this is where four barrels fell in my compound. This is where the mother and child were hurt,” he reportedly said. The attack followed a March 17 one in which at least 21 people were killed.

The UPDF has warned the Nasir-based Nuer militia called the White Army to surrender or perish.

“Our mission in South Sudan has just begun. I want to offer the White Army an opportunity to surrender to UPDF forces before it is too late. We seek brotherhood and unity. But if you dare fight us, you will all die,” said Gen. Kainerugaba.

According to experts, a rise in political tensions in South Sudan and an escalation of violence in the Upper Nile State have raised fears of a return to civil war in the world’s youngest nation.

In early March 2025, neighbouring Uganda sent troops to South Sudan on the request of the government, and was involved in aerial bombardments. South Sudan’s opposition groups took issue with the Ugandan intervention, and stopped taking part in discussions to create a joint military system in the country.

Scapegoating opposition

These developments risk unravelling a 2018 agreement that ended a five-year civil war, created a power-sharing deal between President Kiir, First Vice-President Machar, and other opposition leaders.

Jan Pospisil, an Associate Professor at the Centre for Peace and Security, Coventry University, who has researched South Sudan’s political transition, says the UPDF is raising tensions in the country.

He traces the current tension between Kiir and Machar to clashes that erupted in mid-February 2025 when White Army members attacked soldiers collecting firewood. Four soldiers died and at least 10 civilians were injured by retaliatory shelling from the army.

This incident, he says, heightened animosities, resulting in violent attacks. He says in early March, the White Army, a militia group that defends the Nuer community, launched attacks against units of the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF in which the army forces suffered a humiliating defeat.

“This embarrassed the government – it looked like the national army was unable to control a community militia,” he says, “This provoked a crackdown, and the White Army pushed back. The White Army seized Nasir and parts of the Wec Yar Adiu army barracks on 4 March.”

Another major event was when a planned evacuation of army troops via a UN peacekeeping helicopter on 7 March was disrupted when an exchange of fire led to casualties. At least 27 soldiers died, including Nasir army commander Majur Dak, a Dinka from neighbouring Jonglei State, and a UN peacekeeping crew member.

“In response, the SPLM-led government arrested several opposition figures, including oil minister Puot Kang Chol and opposition chief of staff Gabriel Duop Lam.

Prof. Pospisil says the Kiir government is wrong to scapegoat the opposition. “The government’s narrative suggests that the opposition orchestrated the White Army attacks as part of a broader destabilisation effort in the country,” he says, “However, this ignores the fact that the White Army has historically acted independently.”

According to him, the arrests appear to be an opportunistic move to weaken the opposition, rather than a genuine attempt to address the root causes of the violence. Prof. Pospisil says this outbreak of violence follows patterns of conflict from 2024 and years before. What is different this time is that it has spiralled out of control.

And Pospisil blames the government’s response – including aerial bombardments with the support of the Ugandan army and arrests of leading opposition figures – for inflaming tensions.

Pospisil has extensive field research experience in Sub-Sahara Africa with a focus on South Sudan and Sudan. Over the last years, he has been part of a team conducting the South Sudan public perceptions of peace survey, a project that is continuing in collaboration with Detcro Research and Advisory.

His work focuses on peace and transition processes and political settlements, peace mediation, donor politics in peacebuilding, competitive regionalism, resilience, the Horn of Africa region, and South Sudanese and Sudanese politics.

He is the author of ‘Peace in Political Unsettlement,’ published by Palgrave Macmillan. His monograph on South Sudan as a fragment state has been published in German by transcript in 2021.

Another South Sudan expert, Carlo Koos, who is Associate Professor of Political Science, University of Bergen in Norway, also blames both Kiir and Machar.

Kiir and Machar to blame

He says despite Kiir and Machar signing an agreement in September 2018 that ended a five-year war that killed tens of thousands of people on all sides, the two old men are more concerned about their own political future, their own security and that of their families and allies and ethnic kin.

The 2018 deal, mediated by Sudan and signed in the Ethiopian capital, Addis Ababa, ended a civil war that had been raging since 2013 and reinstated Machar in his current position as vice president.

Prof. Coos has first-hand knowledge of the South Sudanese situation from having worked there as a humanitarian aid worker with Médecins Sans Frontières. He has published a popular essay on the two men entitled `Salva Kiir and Riek Machar loom large over South Sudan’s recent history. And they will keep holding the future of the young nation in their hands to a large extent. So who are they? And what are the roots of their rivalry?’

It was published in the online journal; The Conversation, in May 2022. Prof. Coos says the 73 year-old Kiir and 72-year old Machar appear to be carrying on a long-running feud between their different ethnic groups. He says, ideologically, Kiir and Machar do not seem to be that far apart.

“The difficulty lies in agreeing on how to organise, distribute and cooperate within a nation that consists of dozens of ethnic groups and sub-tribes, different livelihoods, and cultural links across neighbouring countries,” he says.

In the essay, he adds: “It is clear, although they would never admit it, that the two men see themselves and their ethnic communities as the main heirs of the nation, and that they each hold a legitimate claim to leadership.”

Kiir belongs to the Dinka, the largest ethnic group in South Sudan while Machar is from the Nuer, the second-largest ethnic group. The Dinka represent around 35% of the population. The Nuer are around 16%. But there are many other small ethnic groups.

The two men were for many years military commanders under the late John Garang de Mabior, leader of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A that fought for South Sudanese independence from Sudan.

During the fight for independence, both Kiir and Machar disagreed with Garang on the future of South Sudan. Garang wanted Sudan to remain united but with South Sudanese having equal political and economic rights as the north Sudanese. Kiir and Machar wanted an independent South Sudan.

Matters came to a head when in 1991, Machar and members of other tribes formed an opposition rebel movement to the main rebel group SPLM led by Garang. They called their splinter group; the-SPLM-Nasir.

Sensing an opportunity to divide-and-conquer the SPLM, Khartoum used Machar and his troops to turn against the SPLM rebels including Garang and Kiir. They gave Machar and his Nasir faction financial support to fight Garang and Kiir’s SPLM

During the fighting, Machar’s Nasir troops killed thousands of civilians belonging to the ethnic Dinka in what came to be called the Bor town massacre. The massacre sparked reprisal attacks from the Dinka. The ethnic rivalry, attacks, and killings have raged since then.

A peace agreement between the government of Sudan and the SPLM was eventually signed in 2005, paving the way for South Sudan’s independence. Garang became Vice-President of Sudan and president of the transitional government of South Sudan.

When Garang died in a helicopter crash in 2005 en-route from Uganda, Kiir took over the SPLM leadership as well as Garang’s position as Vice-President of Sudan, and became the president of South Sudan. After a landslide referendum in 2011, South Sudanese were granted independence.

Kiir moved ahead of Machar mainly because he was second in charge of the Sudan People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A). He was also a very successful military commander, often leading major offensives against the Sudanese government and capturing large parts of Western Equatoria from Sudanese control.

His military leadership made him popular within the military wings of the movement, together with his strong vision of an independent South Sudan.

Kiir is also generally known for his calm, mild-tempered, and rather emotionless public appearances. As a president, he has shown a thirst for formal authority and power. Machar meanwhile has always been a regional leader. Although he has tried to command all Nuer militias, experts say he has always failed.

UPDF’s not so secret mission

Ugandan troops crossed into South Sudan through Nimule on March 11. Initially it was supposed to be an under-the-radar operation code-named ‘Operation ‘Mlinzi wa Kimya’ or ‘Operation silent guardians.’

It became a public matter when in the early hours of March 11, the UPDF Chief of Defence Forces, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, posted details of the operation on his X handle.

“UPDF Commandos arriving in Juba to support South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) in the current crisis,” Gen. Muhoozi said.

That soon sparked contradictory denials and affirmations in public statements around it in Uganda and Sudan. Uganda’s Minister of Defence, Oboth-Oboth, denied knowledge of UPDF deployment in South Sudan.

“I am not aware of any formal communication that has been made. The deployment could not have happened when I was here, so I will have to verify and inform the House,” he told Parliament.

But the Army spokesperson, Maj, Gen. Felix Kulayigye and the Military Assistant to the CDF, Col Chris Magezi, confirmed the UPDF deployment.

“The UPDF acted decisively on the request of the government of South Sudan to avert a dangerously developing situation and deployed forces accordingly,” said Col. Magezi. He said the decision was taken “in the interest of regional security.”

Then on March 17, South Sudan’s Information Minister, Michael Makuei Lueth, confirmed to journalist in Juba that Ugandan troops had arrived in the South Sudan capital. “The UPDF is here in Juba, and you have seen it,” Lueth, who is the government spokesman and close ally of Kiir, said at a press conference.

“They have come to support their brothers and sisters in the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF),” he said.

He said UPDF support and technical units were in Juba under a military pact between the government of Uganda and the government of South Sudan that dates back to the time of the Lord’s Resistance Army in the late 1990s.

“This is the same pact which is continuing. We have not nullified it, but we use it when necessary,” he said. Since then, the Upper Nile State town of Nasir has endured airstrikes by the South Sudan People’s Defence Forces (SSPDF) and the Ugandan People’s Defence Force (UPDF).

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Who in Uganda gonna tame Muhoozi Kainerugaba! Uncles Saleh or Kagame? Nope. Presently none in the NRM has the stature of either late Kategaya or Amama Mbabazi to confront president Museveni to rein in his son who’s raising all manner of opprobrium that’s damaging to the party, government and the country. A psychiatric evaluation is certainly wanting on the first son otherwise – God forbid – expect a tumultuous presidency!

I support UPDF assistance to South Sudan army. A war there gives us grief, refugees and we lose our market for Ugandan goods.

Gen MK is doing a good job so far. Confident, organised and well respected.

What is the alternative? Sitting back and watch chaos in South Sudan is not a good idea.