E-learning innovations: How digital technology can help reinvent basic education

TECHNOLOGY | Rohen d’Aiglepierre, Amélie Aubert & Pierre-Jean Loiret | African countries have worked hard to improve children’s access to basic education, but there’s still significant work to be done. Today, 32.6 million children of primary-school age and 25.7 million adolescents are not going to school in sub-Saharan Africa.

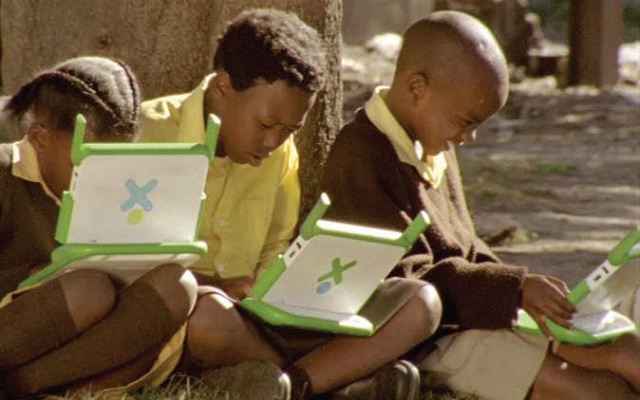

The quality of education also remains a significant issue, but there’s a possibility the technology could be part of the solution. The digital revolution currently under way in the region has led to a boom in trials using information and communication technology (ICT) in education – both in and out of the classroom.

A study carried out by the French Development Agency (AFD), the Agence Universitaire de la Francophonie (AUF), Orange and Unesco shows that ICT in education in general, and mobile learning in particular, offers a number of possible benefits. These include access to low-cost teaching resources, added value compared to traditional teaching and a complementary solution for teacher training.

This means that there’s a huge potential to reach those excluded from education systems. The quality of knowledge and skills that are taught can also be improved.

Access to means of communication is now a key part of daily life for the vast majority of people living in Africa. Mobile telephone prices and the cost of communication have dropped. Mobile telephone use has increased from 5% in 2003 to 73% in 2014. There are 650 million mobile phone owners on the continent (more than the US and Europe combined) and 3G mobile networks are growing rapidly.

Costs are falling and rural areas will soon be reachable thanks to a number of developments. These include undersea cables connecting Africa to other continents, fibre-optic cables that provide connectivity within the continent and recent satellite connection plans. Access to wired Internet remains low with 11% of households connected. But access to mobile Internet is already helping the region catch up. Smartphone penetration levels should reach 20% in 2017.

This rapid expansion of mobile Internet services is already contributing to the region’s economic and social development. This is particularly the case in areas such as financial inclusion (mobile banking), health (mobile health) and farmers’ productivity.

Given the features of mobile telephones (voice calling, text messaging) and smartphones (reading texts and documents, MP3, images and video) and their wide availability, their potential for improving access and quality of educational services is also boundless.

M-learning (or m-education) – educational services via a connected mobile device – is the main lever for growth in educational information and communication technology and for making content available. This could be for learning (teacher training, learner-centred teaching, tests) or making up for the lack of data for education system management.

New technologies for learning

Mass communication technology has been used as a principal driver of education in Africa since the 1960s. Countries such as Côte d’Ivoire, Niger and Senegal developed major programmes using radio and then television to promote basic education, improve teacher training and even teaching pupils directly. These programmes reached a high number of pupils at a relatively low cost. But results in terms of academic performance remain difficult to evaluate.

The mass distribution of computer hardware then took over in the 1990s. Many national and international programmes started to concentrate on equipping schools with computers to facilitate digital education and offer new educational media in the form of educational software and CD-ROMs. Use was mainly centred on schools. But trials were often launched without clear pedagogical objectives and state-defined policy frameworks.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price