For example, piglets would naturally wean when they are around 3–4 months of age. In the U.S., however, piglets are weaned when they are 17–28 days old.

Evans explained that not having access to the natural antibodies present in the mothers’ milk impacts the animals’ immune system. “Abrupt” weaning has also been found to raise the risk of gastrointestinal disease in calves and lambs.

In turn, these diseases call for the use of antibiotics, sometimes prophylactically. For instance, piglets, calves, and lambs can have post-weaning diarrhea and associated infections, so farmers give them antibiotics to prevent such infections.

Also, Evans explained in her talk, a pig’s microbiome “is colonised at birth and subsequently modified during the suckling period” and the weaning period. During this time, the gut microbiome diversifies.

However, research has shown that abrupt weaning, which involves a drastic change in diet and environment, can cause a loss of microbial diversity and an imbalance between beneficial and harmful bacteria in the gut.

Furthermore, genomic studies cited by Evans have found a dramatic increase in Escherichia coli in the pigs’ small intestines after receiving antibiotics. E. coli is responsible for half of all piglet deaths worldwide.

An animal’s environment also plays a critical role in developing a diverse and healthy microbiome. Past studies, for example, found that a pig’s microbiome can be influenced by something as simple as the presence of straw.

Having straw in the environment led to a different ratio of gut bacteria in pigs, and straw has been associated with a lower risk of developing porcine reproductive and respiratory syndrome.

Separated from their mother and with no outdoor access, chicks cannot develop a healthy immune system and microbiome. As Evans noted in her talk, the poultry microbiome is even more affected by intensive farming practices than that of the pig.

The main reason for this is that in birds, the early gut colonisation occurs during the development of the egg in the mother’s oviduct. The chicks absorb microorganisms from the mother at this stage, as well as through the pores of the eggs during brooding.

Once the chicks have hatched, they continue to enrich their microbiome by exposure to feces. However, in modern farming systems, the eggs are taken away from the mother and cleaned on the surface, which removes the beneficial bacteria.

Also, when the eggs hatch, the chicks do not get access to an outdoor space where they would have access to feces and other sources of beneficial bacteria. They also do not interact with adult chickens.

Finally, the crowded conditions that chickens often live in can cause heat stress. This, in turn, is a fertile ground for the development of E. coli and Salmonella infections. This is yet another example of how the environment can affect the birds’ microbiome.

Implications for human health

So, what does this use of antibiotics in animals mean for human health?

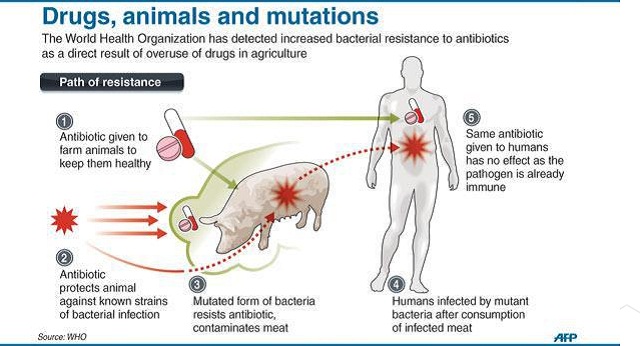

“The most important thing to consider,” Evans said, “is that any single time antibiotics are used, whether in animals or humans, you risk selecting for drug-resistant bacteria. We need to safeguard (antibiotics) for the use in both animals and humans, to ensure they can be used for the treatment of infection in the future.”

There are a few main ways in which antibiotics in animals can affect humans, Evans explained. Firstly, direct contact between animals and humans can cause disease. “For example,” said the researcher, “farmers are at risk of being colonised by the Livestock-Associated MRSA (LA-MRSA).”

“LA-MRSA isn’t as dangerous as (Hospital-Associated)-MRSA,” she explained, “as it is adapted for animals and does not spread as easily from person to person. However, there is a risk that bacteria could change and adapt to humans,” Evans cautioned.

She went on to quote a Danish study that found that 40 percent of commercially sold pork meat contained methicillin-resistant Staphylococcus aureus (MRSA).

A review of existing studies on the pork production chain found that “the slaughter process plays a decisive role in MRSA transmission from farm to fork.”

A second way in which animal antibiotic use can affect humans is through the consumption of antibiotic residues in meat, which then “provide a selection pressure in favour of (antibiotic-resistant) bugs in humans,” Evans explained.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price