Kenya struggles to keep economic grip on Uganda

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Kenya has four big exports to Uganda; palm oil (11.8%) of exports, cement 10.1%, coated flat-rolled iron 8.94%, and refined petroleum 6.27%. Together, these comprise about 40% of Kenya’s total exports to Uganda as of December 2022, according to data from the Observatory of Economic Complexity (OEC); the world’s leading data visualisation tool for international trade data. Those are the latest official figures. Total value of Kenya exports to Uganda was US$677 million.

Ten years ago, in 2012, refined petroleum was Kenya’s biggest export to Uganda. But the portfolio was more diversified and it comprised only 9.27%. Cement featured prominently at 8.83%. But coated flat-rolled iron was just 2.22%. Salt was higher at 3.85%. Total value of exports was US$559 million.

Uganda in 2012 exported almost one item to Kenya; tea at 30.6% of exports. Others were maize at 6.98%, tobacco at 6.18%, glass bottles at 5.04% and beans 4.2%. Electricity exports were just 4.34%. Total value of exports US$237 million.

Ten years later, Uganda has a more diversified portfolio of exports with milk 14.3%, concentrated milk 12.8%, electricity 9.87%, raw sugar 9.72%, unglazed ceramics 5.83%, and plywood 5.44%. Tea and coffee are below 1.0% and tobacco has disappeared. They were replaced by aluminum bars, raw iron bars, and iron blocks and iron wire. Total value of exports US$312 million.

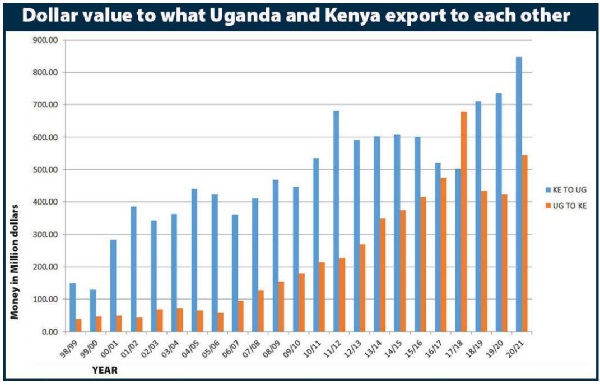

These facts and figures show that between 2012 and 2022, Uganda’s exports to Kenya changed dramatically and their value rose by 30%. Over the same period, Kenya’s exports to Uganda grew by 21%.

Kenya is a bigger economy, with much higher GDP Per Capita (over US$2000). But the slower rate of growth of its exports to Uganda, contrasting with a rapidly growing portfolio of Ugandan exports to Kenya is what is causing what has over time been described as a “trade war” between the two countries.

Kenya’s trade balance with Uganda could worsen in the coming years if Uganda successfully implements its direct importation of petroleum products in the short-term and builds an oil refinery in the long-term. Apart from direct financial implications on the Kenyan economy, that prospect also has a psychological impact. Kenya’s elite have long held the belief that “Uganda lacks options.” But that is changing.

High cost dependence

Historically, Uganda’s political instability, poor economic management, and being landlocked has created a reliance on Kenya which remains its biggest trading partner in the region. Most of Uganda’s imports from other countries also come via the Kenyan port of Mombasa.

This over-dependence on Kenya imposes a high cost on Uganda. For example, Uganda is often shaken whenever political instability, violence or uncertainty rocks Kenya. When post-election violence broke out in Kenya in 2008, Uganda could not import or export to the outside world as hooligans blocked road transport in both directions.

Then Kenya also routinely blocks imports of Ugandan products through non-tariff barriers. By 2021, according to the Bank of Uganda, this resulted in the cumulative loss of about US$121 million.

Ten years later, Uganda has a more diversified portfolio of exports with milk 14.3%, concentrated milk 12.8%, electricity 9.87%, raw sugar 9.72%, unglazed ceramics 5.83%, and plywood 5.44%. Tea and coffee are below 1.0% and tobacco has disappeared.

Historically, being landlocked has been regarded as a disadvantageous position. Landlocked countries are cut off from seaborne trade, which makes up a large percentage of international trade. Thus, coastal regions tend to be wealthier and more heavily populated than inland areas.

When Uganda focused on its land-locked position, the challenges of high trade and transport costs, and limited or low-quality infrastructure were not challenged. Frequent delays at Kenya’s port of Mombasa and at the borders and cumbersome customs procedures and border crossing regulations were equally never challenged. Equally, productivity constraints and structural weaknesses of the economy were accepted as fate. As a result Uganda’s economy remained an import enclave of Kenya.

These disadvantages are not unique to Uganda. It has been for long accepted as the bane of so-called Land-locked Developing Countries (LLDCs). As a result, according to the United Nations (UN), the level of development of LLDCs is about 20% lower than it would be if they had some kind of sea access.

But that mentality is changing.

The UN, under its “Vienna Programme of Action for Landlocked Countries” and its “2030 Agenda for Sustainable Development’ are on a mission to ensure that poor landlocked countries become thriving “land-linked” nations.

“The ability of underdeveloped countries to connect larger growth centres is becoming a significant competitive advantage. It is like the transformation of a destitute neighbourhood that sees a rapid rise in fortune as soon as a minimum threshold of good houses are built,” said one commentator.

The South Asian country called Laos is usually used as an example of a nation exploiting land-locked geostrategic location. Blocked from the South China Sea by Vietnam, Laos has repositioned itself as a land bridge for Vietnam to Thailand and China.

Land-linked not land-locked

Uganda’s evolving emergence as a trade powerhouse appears centred on a shifting attitude from a land-locked country mentality to a land-linked regional orientation.

In the case of Uganda, the concept was popularised by economist and businesswoman Maria Kiwanuka, when she was Minister of Finance, Planning and Economic Development. Maria Kiwanuka always pushed for understanding of Uganda’s geostrategic location in the Great Lakes region. She showed how Uganda’s inland position, with borders with Kenya, Tanzania, Rwanda, DR Congo, South Sudan, and even Burundi which is just one tiny country away, could be a boon, not a curse.

“We are not landlocked. We are land-linked,” she often said, “This makes us a natural distribution hub for East Africa.”

Her selling point was that, transiting Uganda, you can get to these countries by land in four hours or less. The shift from land-locked to land-linked appears to be working.

Uganda has recently emerged as a prime destination for foreign direct investment (FDI) partly because of this “strategic location as a logistics hub within the Great Lakes region”, according to The World Investment Report by the UN Trade and Development released on June 20. It named Uganda among the 10 African countries that attracted the most foreign direct investments in 2023. Kenya was not among them.

The report said other factors that made Uganda attractive to FDIs were its “burgeoning regional trade.” Other factors were stable macro-economic policies and a liberalised business environment.

“The country attracted a substantial US$2.886 billion in FDI in 2023, nearly matching the impressive US$2.9 billion it garnered in 2022,” the report said, “This consistent investment inflow underscores Uganda’s growing appeal to global investors.”

Kenya fights back

Kenya has been fighting back but its strategies appear to be backfiring. The result has been a motley of ugly news headlines. Some ugly headlines include: “Kenya blocks milk from Uganda again” (The Tanzanian Citizen newspaper June 24, 2024). “Uganda’s dairy sector counting losses as Kenya blocks exports” (The EastAfrican July 22, 2023). “Kenya bans maize imports from Uganda” (Daily Monitor March 06, 2021). “How diesel cargo sparked fresh Kenya-Uganda fallout” (Business Daily July 11, 2024).

But there have equally been many headlines showing Kenya capitulating: “Nairobi moves to lift barriers on Ugandan milk, poultry products” (Daily Monitor November 02, 2022). “Kenya, Uganda to end oil import feud over licensing” (Africanews March 28, 2024). “Kenya monopoly of Uganda oil imports to end” (The EastAfrican May 03, 2024).

Other headlines have shown Uganda making its own moves: “Uganda locks out Kenyan firms in oil transport deal” (June 28, 2024). “Uganda Considers Oil Pipeline from Tanzania as Talks with Kenya Stall” (The Pipeline Technology Journal March 24, 2024).

“Kenya oil dealers in panic as Uganda picks Tanga port over Mombasa” (The East African February 25, 2024).This particular one quoted Martin Chomba, chairman of the Petroleum Outlets Association of Kenya (Poak) saying: “If Uganda indeed moves to the Tanzania route, a lot of local oil companies will really suffer because they will lose their biggest market.”

But the most telling headline was: “Museveni gloats about Kenya’s failed attempts to block Ugandan goods” (Pulse August 25, 2023). In this article, President Yoweri Museveni said despite several attempts by eastern neighbours to close out some of Ugandan products, this has not been possible because of their (goods) competitiveness. Museveni was commissioning 16 factories at Mbale Industrial Park in Mbale City.

“One of the speakers here said that when he was young, he thought that this region was part of Kenya because everything used here came from Kenya,” Museveni reportedly said, “But now Kenyan products can no longer be found here.”

Museveni also made note of what he called “failed attempts” by the neighboring country to lock out Ugandan imports. “Indeed the Kenyans sometimes try to block our products, but our products are nearly impossible to be blocked because they are top quality and they are cheap,” he said.

Kenya’s losses

The push to exploit Uganda’s dependence has also led to very big losses for Kenya on a regional scale. Cases usually mentioned are Kenya’s loss of the Uganda crude oil pipeline project to Tanzania and its failure to implement the Standard Gauge Railway project to Kampala. Both were strategic mistakes by Kenya which have led Uganda to open alternative routes to the sea and bolstered Tanzania’s push as a gateway to the Great Lakes hinterland.

Kenya was in pole position to scoop the Uganda crude oil project as early as 2014 when the Uganda-Kenya Crude Oil Pipeline (UKCOP) was proposed. But it soon fell victim to elite capture of all big business in Kenya and the election machinations of the administration of President Uhuru Kenyatta.

This saga is well documented in an article titled: “Rivalry in East Africa: The case of the Uganda-Kenya crude oil pipeline and the East Africa crude oil pipeline” by Brendon J. Cannon and Stephen Mogaka.

When Toyota Tsusho released its feasibility study in 2015, it called for pipeline construction to follow the so-called northern route. Toyota Tsusho supported its decision by citing the need to exploit Uganda’s and Kenya’s existing economies of scale. But, additionally, it cited the benefits of tapping into the integrated Lamu Port-South Sudan-Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) transport corridor project, which, was totally a Kenyan elite agenda. This plan would include a new port at Manda Bay, an airport, an oil refinery and other infrastructure at an estimated combined cost of more than US$25 billion.

“Kenya is an example of countries where raised expectations around oil windfalls contributed to an increase in attempts by elites to gain influence over the oil sector,” says Tom Ogwang of Mbarara University.

The article says, President Uhuru Kenyatta, eyeing a second term, hoped to benefit at the ballot box by highlighting that the northern pipeline route would bring investments, jobs and other associated benefits to that region.

“Kenya favours the northern route through Lokichar, because as part of the Lamu Port, South Sudan, Ethiopia Transport (LAPSSET) project, it would transform infrastructure and the way of life of the people in the towns and counties across its path,’ Manoah Esipisu, the president’s spokesperson said on March 20, 2016.

Reports indicate that Uganda became jittery when the Kenyan government speculatively planned to charge Uganda US$12.60 to US$15.90 per barrel of oil transported through the northern route passing from Hoima to Lokichar and Lamu in Kenya on the northern route. There was also an issue of land and compensation that contributed to higher projected costs in Kenya.

Tullow Oil, one of the partners wanted the Kenyan route, but it favoured a more southern route through Nairobi, thus avoiding areas of insecurity farther north. China National Offshore Oil Corporation (CNOOC), the other major extractor of Uganda’s oil, remained publicly neutral.

Tanzania stepped in when Uganda started exploring other options. It offered to charge US$12.20 per barrel. But significantly it had no land and compensation issues and was also more secure. Then the entry of French oil and gas giant Total SA changed everything. Total SA, the parent company of Uganda’s Total E&P, pushed for routing Uganda’s oil from Hoima south to the west of Lake Victoria, and then southeast toward the Tanzanian port of Tanga.

When President Museveni chose the Tanga route, Kenyans were caught by surprise because of their smugness about “Uganda’s lack of options.” Charles Wanguhu, a coordinator and the Kenya Civil Society Platform on Oil and Gas (KCSPOG), is quoted to have surmised that Kenyan officials had largely taken Uganda’s commitment to the joint pipeline for granted.

A spurned Kenya, for its part, announced that it would build its own stand-alone pipeline to transport its oil reserves to the coast and, in 2018, became the first country in the region to export its oil, the article says.

The standard Gauge rail

In 2014, Kenya, Uganda and Rwanda entered into a tripartite agreement to construct a Standard Gauge Railway from Mombasa through Kampala to Kigali.

But for political reasons, Kenya quickly pushed for and built the Mombasa–Nairobi Standard Gauge Railway and completed the so-called Madarak Express in 2017 – in time for the Madaraka (Self-rule/independence) Day celebrations of June 01, 2017. This move put the financial viability of extending the SGR to Kampala in doubt.

Significantly, beginning in 2018, Kenya extended its SGR from Nairobi to Naivasha and Suswa. This was completed in October 2019 extending the line’s length by 120 km from its original length of 472 km. But, at a cost of US$3.6 billion, the SGR was among Kenya’s most expensive infrastructure projects. Today, it is cited as one of the White Elephant projects that pushed Kenya on a slippery path to huge debt which almost led to its sovereign debt default. As of 2020, the SGR operation expenses exceeded revenues.

After Kenya’s moves, President Museveni frantically started searching for his own SGR project financing in 2021. But with doubt sown that Kenya would not build its SGR to the Uganda border at Malaba, the Exim Bank of China was reluctant to get involved. In November 2022, Uganda formally terminated its contract with China Harbour Engineering Company (CHEC) awarded in 2015, to build the first phase of SGR, a 273km stretch from Malaba to Kampala.

Today, reports indicate there is renewed pressure on Kenya and Uganda to extend the SGR to, especially the resource-rich DRC. The pressure is posed by Tanzania’s push on with its electrified line headed in the same direction on the Central Corridor. Tanzania’s US$7.6 billion project runs over 1,600km from Dar es Salaam to Mwanza on the shores of Lake Victoria and Kigoma along Lake Tanganyika.

In May 2024, Uhuru’s successor, President William Ruto announced that Kenya and Uganda had agreed to jointly extend the Standard Gauge Railway from Naivasha to Kampala to DR Congo.

Kenya blocks Uganda petroleum

But the new moves are being made under the dark cloud of recent economic-inspired riots in Kenya and another running battle between Uganda and Kenya over Uganda’s bid to bypass Kenya in its importation of refined petroleum products. Once again the headlines are ugly.

Under the banner: “Kenya, Uganda agree to explore extension of Eldoret-Kampala pipeline” (Citizen Digital May 16, 2024) it was noted that Kenya and Uganda had signed a tripartite agreement allowing Uganda’s state oil firm to import her petroleum products through Kenya.

“The Tripartite Agreement on the Importation and Transit of Refined Petroleum Products through Kenya to Uganda whose signing we have just witnessed enables the Uganda National Oil Company Limited to Import refined petroleum commodities directly from producer jurisdictions thus bringing to an end the challenges faced by the sector in Uganda,” stated Ruto.

But that announcement came after Uganda sued Kenya at the East African Court of Justice on December 28, 2023 accusing it of denying the Uganda National Oil Company (UNOC) rights to operate as an Oil Marketing Company (OMC) in Kenya.

Kenya insisted the Uganda oil pipeline project was not beneficial to Kenya.

“The pipeline is not utilised as it should, the deal is expensive but we are not getting profit as we should,” Kenya Government Spokesperson, Isaac Mwaura, said according to Citizen Digital (January 11, 2024).

“Regardless, this is something that benefits Kenyans; we have a right to benefit from the measures we have put to collect revenues on top of other needs.”

Not surprisingly, a few months after Ruto’s May announcement, another ugly headline popped up: “Nairobi slaps Uganda with fresh hurdle on fuel imports (The EastAfrican Tuesday July 09 2024). This one described fresh hurdles that Kenya had thrown on Uganda’s direct fuel import scheme, doubling the bond fee for imported consignments destined for Kampala to US$45 million.

It quoted Uganda’s Energy and Mineral Resources minister Ruth Nankabirwa saying Kenya increased the requirement on the size of bond fees at the Vitol Tank Terminal International (VTTI) storage facility in Mombasa from US$15 million —posing a bottleneck to Uganda’s hopes of lowering pump prices of the commodity. That one is yet to be resolved.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price