Lessons from COVID show it’s a bad idea

COVER STORY | THE INDEPENDENT | Since the first case of the current Ebola outbreak in Uganda was confirmed on September 20, the number of cases had by November 04 topped 131 across seven districts, including 17 in the capital city Kampala. Case Fatality Ratio (CFR) among confirmed cases is 48/131 (37%).

A total of 1,604 contacts actively being followed-up in eight districts, with follow-up rate of 93%, according to the World Health Organisation (WHO) situation report of Nov.04.

By this time most people living in Kampala city fear another round of lockdowns perhaps even more than they fear becoming infected.

“Kampala should have restriction of movement. Let us hold Kampala when it is still early. The earlier we lock down Kampala, the better,” said Dr. Samuel Oledo, president of the Uganda Medical Association (UMA) on Oct.24.

Two high-risk districts have already completed a 21-day lockdown announced by President Yoweri Museveni on Oct.15. Mubende district, which is the origin of the outbreak and neighbouring Kassanda, which has recorded the highest number of cases, completed the lockdown on Nov.04.

And although the government says it is not considering Kampala high risk at the moment, it has not shied away from using the “threat” of lockdowns to try to persuade people to conform to the health procedures. These include reporting suspected cases, supporting contact tracing and undergoing isolation where potential exposure to an infected person has taken place.

“We don’t expect any lockdown, at least as of now. There is no indication of a lockdown in Kampala. If the situation changes significantly, the National Task Force chaired by His Excellency President (Museveni) will discuss it. But as of now, the situation does not warrant a lockdown,” says Dr. Henry Mwebesa, the Director General of Health Services. But, he adds, the National Ebola Task Force will advise on it if the Ebola spread threatens to get out of control.

“The penetration of Ebola in heavily-populated areas creates a situation of rapid spread and is associated with sustained and protracted person-to-person-transmission. Urban Ebola transmission is complex and the government will do all it takes to ensure the control of transmission in the urban settings,” says Dr. Ruth Aceng, the minister of Health.

Dr. Aceng also revealed on Oct.30 that the Ministry of Education and Sports could consider early examinations for non-candidate classes so that schools can close early for the third term holidays.

“The fewer the learners at school, the easier for us to carry out surveillance and ensure that learners are safe,” she said. She later clarified that the government plan is not to close schools.

Fears about an Ebola lockdown are based on the impact of severe lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic. Uganda first had an extended lockdown from March 2020 to June 2020. Many Ugandans recall the lockdown days with fear over hunger, widespread poverty, and harassment by lockdown enforcers.

Bad economy

If an Ebola lockdown is declared, it will be against the backdrop of an economy that has not recovered from the economic crisis associated with the COVID-19 pandemic, coupled with other global inflationary pressures.

The World Bank estimates that Uganda’s economic growth will be 3.7 percent in 2022, which is lower than pre-COVID-19 projections of over 6 percent.

“Rising commodity prices and the overall increase in cost of living pose new risks to livelihoods that had just begun recovering from the effects of COVID-19. These and other shocks are threatening to stall socio-economic transformation, thus increasing the likelihood of the people falling deeper into poverty,” said Mukami Kariuki, World Bank Country Manager for Uganda, at the launch of the latest World Bank economic update on the country.

The new global shocks, include the spreading impacts of global inflation and the war in Ukraine.

The fear of an Ebola lockdown by, especially Kampala city residents, is warranted because a functioning economy, especially in highly vulnerable communities in urban areas, is crucial to population health. Locking down Kampala will send the national economy in tailspin.

Kampala City district and its eight neighbours grouped under the Greater Kampala Metropolitan Area (GKMA) contributes 31.2 percent of Uganda’s Gross Domestic Product (GDP), offesr about 50% of formal jobs and over 70 percent of industrial production.

Blanket enforcement of lockdown measures may help to slow down the spread of a virus but it is now known that it can also quickly generate a larger and more protracted public health crisis in the form of deprivation and hunger.

Researcher Astrid R.N. Haas has been involved in a project, alongside Asim Khwaja, director of the Centre of International Development at Harvard University, and Adnan Khan, professor at the London School of Economics and Political Science, to develop a more nuanced containment approach.

They analysed different approaches adopted by countries across the globe during the COVID-19 pandemic. Based on their analysis, they developed an approach they termed “Smart Containment with Active Learning”.

Published in the May 2020 policy brief by the Centre for International Development at Harvard University and the International Growth Centre, the argument for their smart containment is based on the COVID-19 containment measures. They say protracted, blanket national-level lockdowns are likely to be inefficient and costly instruments while refocusing on localised measures of ‘smart containment’ could enable the government to both respond to the health crisis and limit economic consequences which is key.

The smart containment strategy

Their smart containment strategy involves a graded action plan with four levels based on cumulative severity of disease outbreak. At each level, the containment involves smart testing and data collection and use, recommended levels of physical distancing, community messaging, and actionable decisions.

At Level 1, there are no infections identified yet. This period is for preparation. There is testing for high risk/high impact individuals e.g. health care workers, including questionnaire to understand symptomatic presentation (syndromic surveillance). There is also dedicated surveillance through a targeted network of reporting sites (sentinel surveillance). At this level emphasis is on basic physical distancing measures, standard health practices (hand washing, wearing masks etc.), and protective organizational and management practices.

By Level 3, infection has been detected and the spread projections are severe, underlying vulnerability is high, and population is high impact and/or high health risk. There should be extension of testing and contact tracing of high risk workers in areas adjacent to breakout areas too (including surveillance robocalls). There should be isolation of confirmed cases and quarantine of contacts but no full lockdown. Surveys of recovered cases, ongoing prevalence, and phone surveys to garner more information about symptoms that could indicate a re-outbreak. It is important to collect socioeconomic indicators to effectively respond to vulnerability.

In terms of physical distancing, full restriction on the movement of people within specific area for a specific short period is recommended until there are only a very low number of infections ensuring that people have the necessary essentials (food, water, health items) for the duration of the period. Potential quarantine of adjacent areas, where there is high risk of transmission is recommended.

At the highest Level 4, there is widespread disease. Here a full lockdown within specific area is recommended with quarantines and isolations measures in adjacent areas until there are only a very low number of infections (or based on anti-body testing). A higher level of complementary welfare and health support may be needed. Additional preventative and protective measures for vulnerable populations (e.g. elderly and health care workers) from getting infected.

They argue that within this framework of active learning, even governments with limited capacity can develop graded and data-responsive smart containment policies and that, once operationalised, these plans will help generate further evidence for policymakers, leading to better contextualised and sustained solutions.

This requires policy makers to find ways to handle a public health crisis without creating an economic one. Containment options must be informed by local conditions and suit varying circumstances. They should be reviewed and continuously updated with incoming data and evidence.

The approach they outline has implications for managing the current Ebola outbreak in Uganda as well as future health epidemics.

The human cost of blanket lockdowns

There is no agreed explanation about why the health impacts of COVID-19 were lower in some African countries, including Uganda, when compared against global rates. Still, the economic consequences, particularly of the lockdowns, were severe.

A Working Paper entitled ‘Estimating income losses and consequences of the COVID-19 crisis in Uganda’ by the International Growth Centre (IGC) says despite the country having relatively few cases, the pandemic’s indirect effects arising from an economic contraction and global recession, as well as the direct effects through ill health and death, are likely to have a devastating impact on poverty levels and people’s livelihoods.

The researchers, using income data, calculated that every month of lockdown results in losses of 9.1 percent of monthly GDP; resulting in a 3% decline in annual GDP in 4 months. They also point out that exposure to the shock is similar in Kampala and other urban areas, with 68 and 72 percent of households in these areas losing income, respectively. And, they point out, even in rural areas, the impact is not much less.

“Another unexpected result is that the total loss in income is larger in rural areas than in Kampala and close to that in other cities, by virtue of the much larger population in rural areas,” the researchers say, “So while much of the focus of popular discussion has been on Kampala, there is a comparable crisis in other cities and a larger, if more diffuse, crisis in rural areas.”

The researchers conclude that economic losses across Uganda as a result of lockdowns affected over 65% of the population and nearly ten years of poverty eradication efforts were erased.

The most extreme economic effects were felt in Kampala. Residents experienced an increase of 16.7 percentage points in poverty rates. Income inequalities also rose, represented by a 10.5% increase in the GINI coefficient.

The Gini coefficient is a summary measure of income inequality. It incorporates the detailed shares data into a single statistic and summarises the dispersion of income across the entire income distribution. The index ranges from 0, indicating perfect equality (where everyone receives an equal share), to 100, perfect inequality (where only one recipient or group of recipients receives all the income).

Explaining the impact of the crisis on inequality, the researchers say that nationally (and within rural areas), the impact on inequality is minor, but in Kampala the Gini coefficient increases by 10.5 percentage points, and in other urban areas the increase is 4.7 percentage points.

“This sharp rise in inequality for Kampala is due to the fact that many people who earned incomes near the middle of the income distribution (before the crisis) now have zero earnings,” they say. This was because many in the city could not earn a living at all for certain periods of time during the lockdown.

There are also likely to be long term effects on economic productivity, which remain to be seen. For example, Uganda closed schools for two years – the longest period of any country.

It’s not yet possible to adequately quantify these losses. Nevertheless, based on evidence from school closures elsewhere, this is likely to lead to a less skilled labour force and lower incomes. There are also likely to be significant associated social costs.

The reasons that Kampala fared worse than the national average lies in the overall structure of the city’s economy. In 2016 the World Bank surveyed informal businesses operating in the greater Kampala area. It showed that most businesses operated in the informal sector and were very small, with 46% employing fewer than five people.

Most importantly, 56% of owners said they engaged in trade and the services industry. And 93% of these microenterprise owners were, at the time of the survey, already operating close to the poverty line, or just beneath it.

When the lockdown was imposed, these businesses were no longer able to trade. Many of their owners and the households they supported would have been pushed far below the poverty line.

In urban areas like Kampala a high proportion of income is used to buy food. The blanket lockdowns resulted in 17% of Kampala’s population facing acute food insecurity and increased consumption gaps. A 2020 analysis by the Integrated Food Security Phase Classification, an innovative multi-partner initiative for improving food security, nutrition analysis and decision-making, showed that 17 percent of Kampala’s 3.5 million residents, or 292,330 people, experienced adverse levels of acute food insecurity and had increasing food consumption gaps and reduced dietary mixture.

Smart containment strategies

The concern by the Ministry of Health in Uganda and the World Health Organisation over the latest outbreak of Ebola in Uganda is warranted. The current strain of the virus circulating in Uganda, the so-called Sudan strain, does not yet have an approved vaccine and has an estimated case fatality rate of 40%-60%.

The 2014-2016 Ebola outbreak in West Africa – caused by a different strain – resulted in 28,600 cases and 11,325 deaths. The case rate significantly increased once the virus hit the densely populated urban areas of Conakry, Freetown and Monrovia.

Containing the current outbreak, particularly in Kampala, is therefore critical.

But containment needs to be done in a smarter way than was the case in the COVID pandemic. Contagion risks need to be weighed up against the benefits of maintaining economic interaction.

The researchers conclude in their policy brief that containment doesn’t need to take an all-or-nothing approach. Gradations need to be considered.

Any smart containment strategy requires accurate and up-to-date data on disease prevalence, trends and transmission. And, critically, regular socio-economic data also need to be collected to assess growing risks, particular in relation to poverty and hunger. This data should then be used to drive the analysis that underpins the policy decisions about when, where and how to impose restrictions – and lift them.

These decisions should be taken in a more targeted and flexible way, below district level, to ensure that containment is commensurate to localised information, which, in turn, will be far less economically costly.

The second part of a smart containment strategy is that it needs to be dynamic, and changes should be made based on updated information. This is what we termed “active learning”. Here, again, data play a key role, in continuously assessing the risk profile of an area.

This does not only have to be geographical, but can also be related to different sectors. For example, interactions with high contagion risk and limited economic value, such as sporting events, may be fully shut down for a period, while in the same area, activities that support the livelihoods of vulnerable populations may continue, adapted to meet health and hygiene standards.

Finally, continuous evaluations of policy responses are important in supporting this active learning.

Communication is key

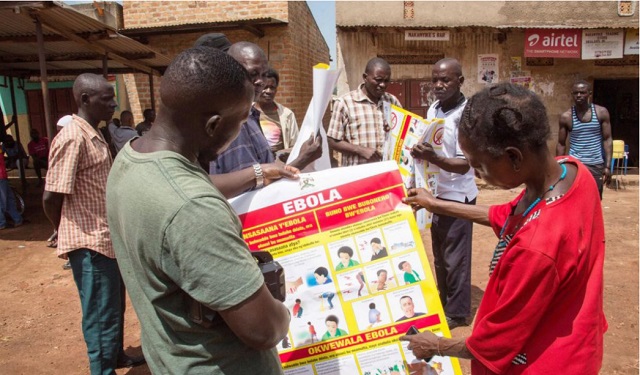

Underpinning such a strategy is clear, credible, transparent and regular communication on what is happening and why it is happening. There is evidence from Sierra Leone during the last Ebola outbreak that effective messaging that makes use of citizens’ agency and self-efficacy is key in securing community support for containment measures.

It’s also important that the messaging focuses on de-stigmatising individuals and minorities, so that those who are potentially infected feel comfortable taking proactive measures like self-isolating and seeking medical care.

In the longer term it helped increase trust in authorities, popular understanding, and support for further measures, unleashing a positive cycle that ultimately ended the epidemic.

****

This article is based on research publication by Astrid R.N. Haas, Fellow, Infrastructure Institute, School of Cities, University of Toronto.

Source: The Conversation

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The government should rather put in place strict laws to curb the spread of ebola.