COMMENT | Gertrude Kamya Othieno | The relationship between Africa and Europe over the last 600 years has been anything but equal. What began as mercantilist trade expanded into a complex system of exploitation that evolved into modern capitalism. This dynamic redefined Africa, not as a continent of innovation and agency but as a resource base for European wealth. The effects of this encounter were not limited to the past; they continue to reverberate today, shaping Africa’s political, economic, and cultural realities.

The Mercantilist Beginnings

In the late 15th century, European powers began to explore and exploit Africa’s wealth under the guise of trade. Mercantilism, the dominant economic model of the time, was built on the premise of accumulating wealth for European states through trade imbalances and the control of resources. Africa’s rich reserves of gold, ivory, and other commodities made it an attractive target.

This early phase of exploitation reached its peak with the transatlantic slave trade, where millions of African men, women, and children were forcibly taken from their homelands. Commodified as labour, they were transported to the Americas to work on plantations, fuelling European economies while devastating African societies. The human cost was incalculable, as entire communities were destroyed, and Africa’s population was depleted of its most productive members.

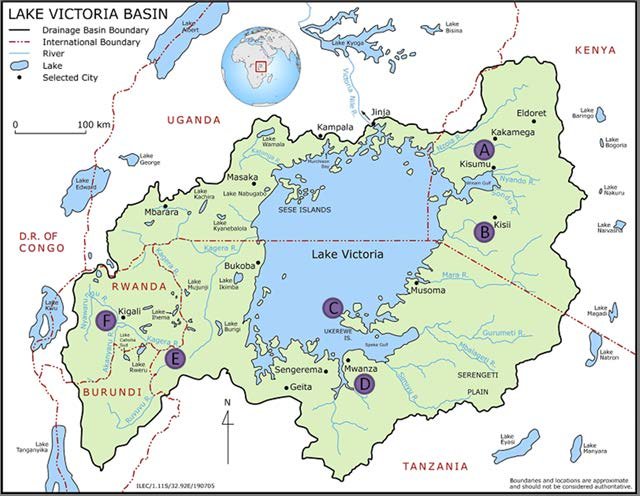

Even Africa’s geographical identity was reshaped. European explorers renamed rivers, mountains, and lakes, claiming them for their nations and erasing their African significance. The Great River of Mali became the Niger River, and Lake Nalubaale was rechristened Lake Victoria. These acts of renaming were not just geographical but psychological, symbols of dominance and ownership that alienated Africans from their land.

The Transition to Capitalism

As Europe moved from mercantilism to capitalism during the Industrial Revolution, Africa’s exploitation deepened. The continent became central to the European industrial supply chain, providing raw materials like cotton, rubber, and minerals. These resources were extracted under colonial rule, often through forced labour, and shipped to European factories for processing.

Colonial administrators restructured African economies to prioritise resource extraction over local needs. Traditional subsistence farming was replaced with cash crop economies, leaving African communities vulnerable to food insecurity. The wealth generated by these systems flowed outward, enriching Europe while impoverishing Africa.

The Ideological Justifications

This exploitation was justified by ideological constructs that framed Africa as a “backwards” continent in need of European civilisation. Missionary schools taught African children that their languages, customs, and religions were inferior to Western ideals. Traditional knowledge systems, which had sustained African societies for centuries, were dismissed as primitive.

This narrative not only facilitated economic domination but also undermined African identity. By instilling a sense of inferiority, European powers created a psychological dependency that made resistance more difficult.

The Lingering Effects

The legacy of mercantilism and capitalism continues to define Africa’s place in the global economy. Post-independence nations inherited economies designed for resource extraction rather than self-sufficiency. Trade agreements and debt structures imposed by international institutions like the IMF and World Bank further entrenched Africa’s dependency on external powers.

This dependency is not limited to economics. African leaders educated in colonial systems often internalised Western ideals, perpetuating the very structures they were meant to dismantle. Today, Africa remains a supplier of raw materials, a consumer of foreign goods, and a recipient of aid, roles that mirror the mercantilist dynamics of the past.

Toward Reclamation

Despite this history, Africa’s resilience can not be overstated. The continent has preserved its rich traditions of communalism, innovation, and cultural diversity, offering a foundation for reclaiming its narrative. The task now is to confront the structures of dependency and demand reparations for centuries of exploitation.

In the next essay, we will explore how mercantilism and capitalism disrupted Africa’s traditional systems of governance, culture, and resource management, creating the conditions for economic and social dependency that persist to this day.

****

Gertrude Kamya Othieno | Political Sociologist in Social Development (Alumna – London School of Economics/Political Science) | Email – gkothieno@gmail.com

Gertrude Kamya Othieno | Political Sociologist in Social Development (Alumna – London School of Economics/Political Science) | Email – gkothieno@gmail.com

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price