We would unashamedly campaign for Okurapa again as Makerere Guild President were the clock to wind back

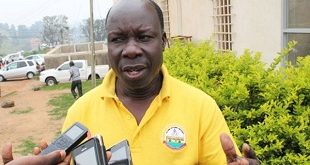

TRIBUTE | Alfred Geresom Musamali | Around February 1985, forty (40) years ago, Uganda’s Makerere University Northcote (now Nsibirwa) Hall chairman Maurice Rutakingirwa (RIP) and I, a then Northcote-based ruling Uganda People’s Congress (UPC) youth activist, were among the fellow students that successfully campaigned to elect George Okurapa as the university’s Students Guild President. Dark-skinned, not very tall Son of Teso, Okurapa (some adversaries derisively called him Okuraption!), with slightly protruding eyes which you would not notice if he was in spectacles, and developing side whiskers which he would in future suppress by constantly shaving, was standing on the ruling party’s ticket. From the outstart, l must point out (especially to our Canadian readers, among them Okurapa’s own children!) that this origin in Teso, whose people are called the Iteso and whose language is Ateso, is central to my narrative. Teso is comprised of vast, relatively sparcely populated peneplains punctuated by inselberges in the north-eastern subregion of Uganda as well as in parts of western Kenya. It is equally important to point out further that I am from Bugisu, the Mt Elgon/Masaaba sub-region on the immediate southeast of most Ugandan parts of Teso. Bugisu is predominantly the ancestral origin of the Bagisu/Bamasaaba (the language is Lugisu/Lumasaaba) but those on the Kenyan side are Babukusu/Bamasaaba. And Rutakingirwa was from Rukungiri in the Kigezi, the sub-region in the south-western tip of Uganda near Bushenyi from where Edidah Kasingura, Okurapa’s future wife, originated.

On July 27th that year, however, the UPC government led by Dr Apollo Milton Obote was overthrown by the military junta of Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA) Generals Tito Okello and Bazilio Olara Okello, both from Acholi which neighbours to the north Dr Obote’s ancestral land in Lango, itself in Uganda’s northern parts. Both Lango and Acholi are to the north-west of the Ugandan parts of Teso – and this geographical location will, too, have a bearing on my narrative. The generals immediately appointed former Makerere University Guild President Dr Olara Otunnu, hitherto Dr Obote’s very trusted Permanent Representative to the United Nations (UN), as foreign affairs minister. In turn, Okello, Otunnu and all were on January 26th, 1986 swept out by the National Resistance Army/Movement (NRA/M), which Dr Obote had always referred to as a batch of “bandits and bushmen”. The NRA/M were led by now President Yoweri Museveni who had been fighting a five year protracted guerilla war in what was called the Luwero Triangle. The Triangle comprised of Luwero, Mpigi and Mubende (although some people have insisted that it was a Quadrilateral because it included Mukono) districts that surrounded Kampala, Uganda’s centrally located capital city. Okurapa is, therefore, on record for having unenviably held the Makerere Guild Presidency across a transition involving three heads of state and two military coups.

The coup found Okurapa and a select few other fellow Ugandans at the 12th World Festival of Youth and Students in Moscow, Russia which was by then part of the Union of Soviet Socialist Republics (USSR). Others at the conference were former National Union of Students of Uganda (NUSU) national (as opposed to Makerere Branch) President Paul Masaba (a Human Medicine Year 4) and incumbent national President Kaboyo Kisoro (RIP) who had already written his final examinations for the Political Science and Public Administration (a three year course). Given that they were continuing students, the first dilemma Okurapa and Masaba faced was whether to return to Uganda at all or to seek refuge wherever, foregoing the studies (whether temporarily or permanently). As for Kaboyo Kisoro, he presumably did not even bother to show up again in Uganda.

Okurapa and Masaba did brave themselves and come back to Makerere. After writing his last examinations in June 1986, though, Okurapa was held without charge on the orders of Makerere alumni Gregory Mugisha Muntu who had come to office as chief of military intelligence under the NRA/M. Then in January 1987, after six months in captivity, Okurapa somehow escaped and fled to exile, first to Kenya then to Toronto, Ontario Province, Canada. He only returned to Uganda briefly in 2023 following reconciliation with Mugisha Muntu (who eventually rose to become army commander but is now a retired general leading an opposition political party, anyway!) and security clearance from President Museveni.

Okurapa succumbed to cardiac arrest on Saturday, January 11th this year (2025) when he was back in Canada and his remains have been repatriated for burial scheduled for Saturday, 22nd February, 2025 in his ancestral village of Komuge, Kachumbala subcounty, Bukedea district in Uganda’s Teso sub-region.

I would, however, unashamedly campaign for Okurapa again today were the clock to be wound back so that I return to that Year 3 Literature 3.1.1 course I was undertaking during the 1984/85 Academic Year, he offers himself for the guild elections and outgoing Guild President Ogenga Otunnu, the nephew of General Olara Okello and young brother of Olara Otunnu, again steered trouble at Campus, threatening my completion of the course. Olara Otunnu fled back to the United States on the Okello-Okello junta collapsing. In more recent times, though, after Dr Obote died in exile in Lusaka, Zambia and Uganda returned to a multi-party dispensation, Olara Otunnu reemerged in Uganda, without any passport (although he is alleged to have carried one of Côte d’Ivoire) and became a UPC party president. Ogenga Otunnu is now reportedly an academic at some Canadian university. He is also author of a 2017 book entitled “Crisis of Legitimacy and Political Violence in Uganda between 1979 and 2016” (Published by Palgrave Macmillan).

February was both the climax of student politics and Year 3 Literature in Makerere those days

Makerere in those days had a term- rather than a semester-based academic year. The year started in September/October, with Term 1 running till December. Term 2 started in January and stretched up to February/March. Then the Term 3 stretched from April to May/June. While those of us in the so called “flat” courses ended the academic year in June, the professional courses, in addition had a Term 4, covering from July to August/September. But whatever the course of any student, campaigns, elections and handovers to positions of responsibility at university level took place in February, thus placing the month at the climax of student politics. Typically, it was the Year 2s that offered themselves for elections but in some four year courses such as Engineering and Veterinary Medicine and in Human Medicine, the five year course at that time, students beyond Year 2 could still contest for elections. And whether the student was in a professional course or in the so called “flat” course, the end of academic year examinations (generally referred to as Onyango’s Disco by virtue of long-serving Academic Registrar Bernard Onyango being at the centre of their administration) were in June. But in Literature (which I was pursuing as a 3:1:1) there were no Year 2 examinations because most coursework for papers such as Drama (taught by our very own Maria Karooro Okurut), Poetry (by again our own Prof Timothy Wangusa), Special Authors (Joseph Conrad taught by the Late Austine Eject and William Shakespeare by Karooro), Oral Literature (also called Orature and taught by Charles Okumu) and the Art of Communication (taught by the Late Dr Katebalirwe Amooti wa Irumba) were spread over a two academic year period, with the examinations only coming at the end of the entire course. The 3:1:1 was an expression in the science and arts so called “flat” courses and meant that the students took three disciplines in first year but dropped two and remained with only one in Year 2 and 3. The alternative was the 3:2:2 where the students retained two disciplines after Year 1.

The 3:1:1 required a deeper and wider study of each discipline than the 3:2:2. The Literature programme also had funny combinations of “half-papers” that had to be combined to make the full paper in a discipline. For instance, a student could opt for one Special Author (that is a half-paper) and either only the theory part of Orature or the Art of Communication to make a full paper yet the full paper in Special Authors would have involved two authors, the theory and project in Orature would make another full paper and so did the theory and project in The Art of Communication (that is a total of three papers). My Orature project was an anthology of Lugisu/Lumasaba folktales whose manuscript has since gotten lost. Each of those full papers really called for in-depth study. The Special Authors, for instance, called for the study of about eight texts of each author which, climaxing in February of Year 3 was quite a challenge.

Other than the eight of us in Literature 3:1:1 , there were about fifty of the 3:2:2s of Literature and English Language Studies (ELS), mostly teacher trainees such as now Mass Communications guru Prof Monica Balya (Mrs Chibita), and some others who combined Literature with Political Science, History, Religious Education or Linguistics without being concurrently teacher trainees because the only discipline that concurrent teacher trainees could combine with Literature was ELS.

By February 1985, the teacher trainees in our cohort had at least already sat their Year 2 ELS examinations and taken their Teaching of English as a Second Language (TESL) School Practice Stage 1 so they only had half the load. Even those who were combining Literature with another discipline or not opting for Literature at all had only half the load pending. What was remaining at stake for them was, therefore, not as heavy as it was for us in the Literature 3:1:1, with every lecturer winding off the course and the project handing-in dates looming. For Rutakingirwa, on the other hand, Year 3 of Human Medicine were clinicals which had even higher stakes because from time immemorial the examinations of that stage determined whether you transited to becoming a medical practitioner or you just returned home with your Advanced (A) Level secondary school certificate.

By February 1985 Inflation was still raging and heavily influencing Makerere student politics

Meanwhile, inflation was biting hard. The GoU set salaries and allowances for its employees at the beginning of the Financial Year (FY) but they would nevertheless get dwarfed by multiple digit inflation within a few months. The same applied to allowances for students in institutions of higher learning, among them for Books and Stationery, Out of Pocket (popularly called “Boom” and basically spent by some of us on crude alcohol in the slums surrounding Makerere!), Transport to and from home districts during term breaks (some also got the money then remained “fluking” on Campus, anyway!), Non-Residence (NR) allowances for the extremely few students not accommodated on campus as well as special faculty allowances for professionals undertaking fieldwork or other practicals during Term 4. However, while to offset the onslaught of inflation the beneficiaries of the payments agitated for more short term increases, some economists such as now Prof Ephraim Kamuntu were of the view that GoU should, instead, focus more on long term establishment of peace (which proved to be wishful thinking, anyway!) and incentivizing production of cash crops (coffee, cotton, tea and tobacco), minerals (mainly copper) and manufactured goods (agricultural inputs, textiles and beverages) in the post-Amin war-ravaged economy so that their increased supply could tame the inflation.

I remember that President Obote, who was also the Finance Minister, had increased the salaries and allowances of the public servants by 450% at the beginning of the new FY on July 1st 1984 but by December of the same year those payments had already been rendered meaningless by inflation. The student allowances suffered a similar fate. And because the age of self-sponsorship at the university had not yet arrived, the only students not sponsored by the Government of Uganda (GoU) and, therefore, not affected by GoU decisions on allowances were international ones in Statistics, Library Studies and one or two other professional courses presumably not available in their own countries.

Thus, at Makerere there arose two camps over the allowances. The, in my view, populist camp was hell-bent on rebellion so as to arm-twist the GoU into again increasing the allowances – including by generating propaganda that cast GoU in a bad light and by disrupting programmes at the risk of closing down the Campus. In this group were those more inclined to the Democratic Party (DP) which had opposition representation in Parliament during day but were, nevertheless, suspectedly collaborating with the NRA/M at night. The non-populist camp, again my view, had ex-seminarian Rutakingirwa and myself who, while really in need of more money, did not wish to see any programmes disrupted by premature closure of Campus because we had higher stakes in it that our cohort mates. The battlelines between our camps over allowances that year came out most prominently in the February nomination of candidates for various hall of residence, guild, sports union and NUSU (Makerere Branch) position elections.

We campaigned for Okurapa because he was pro-government, pro-peace and pro-continuity

Okurapa (who I had left in Ngora High School as newly elected head prefect, by the way!), was in Year 2 of Political Science and Sociology that February. Before he came to Ngora (in Teso, his ancestral subregion) for A Level secondary, he had attended Ordinary (O) Level in Jinja Secondary School, between 1977 and 1979, but had transfered to Moroto High School in the semi-arid Karamoja sub-region on the immediate north-east of Teso and also in the immediate north of Bugisu. In Karamoja, he sat for his O Level in 1980. Ironically, insecurity among the semi-nomadic Karamojong (people of Karamoja) following the overthrow of Idi Amin was higher that in Jinja (mid-eastern), 80 just kms from Kampala but I have failed to establish the rationale for such a transfer. In Jinja, Okurapa had been a student leader and, with such a background, I was confident about his leadership potential. Besides, we considered him the most government-leaning, pro-peace and pro-continuity candidate in the face of DP double-facedness over NRA/M skimishes. I remember that he also had good connections with Peter Iloot Otai, the state minister for defence who was also from Teso. Through Otai, we got some small political support, perhaps the printing of posters, the hiring of public address systems, hiring of a campaign car or other such simple logistics before we could go through the party primaries and the party takes over. We also got a lot of encouragement from a now either an unemployed or newly employed graduate called Lima lo Lima. Hardly having any means of his own, Lima lo Lima (to whom I shall return later) nevertheless appeared at the Campus a few times to boost our morale. Ogenga Otunnu, though, the outgoing Guild President who had been elected on a UPC ticket and from whom we expected more, had since had his differences with the university party branch led by (now Prof) Adipala Ekwamu. Ogenga Otunnu, therefore, relentlessly but unsuccessfully put every obstacle in the way of Okurapa or any other UPC for that matter getting elected. One of his rationales was, and rightly so, that the political parties need not pop their noses into student politics.

As he came towards the end of his term of office, Ogenga Otunnu led others, especially in his Political Science and Public Administration or other Social Science Year 3 cohort, into making the populist demands for improved allowances. In the cohort were now Ambassador Richard Kabonero, Fred Guweddeko who I last heard of at the Makerere Institute of Social Research and George Okello Lucima who had beaten me a year earlier in the race for the presidency of the NUSU Makerere University Branch, George Wanda who could be in the United States (US) as well as Wamasali Siende, Sam Sakwa Napokoli who are now elders in Bugisu. Some of them in the cohort joined Ogenga Otunnu but others just remained unbothered, presumably because their stakes were not as high as those of Rutakingirwa and myself.

Every morning, the Ogenga Otunnu group converged at the Freedom Square, singing, dancing, sloganeering and making it almost impossible for lectures to smoothly go on in the neighbouring Department of Music, Dance and Drama (MDD), Arts Court, Faculty of Social Sciences and School of Librarianship. On one occasion, they did invade the lecture rooms to disrupt studies and compel academic staff to stop work, with some staff most happily packing up to go mind their petty businesses outside Campus. Those were the days when most private secondary schools surrounding Makerere were staffed by Makerere lecturers, incidentally, so when chased out of class the lecturers would not really have lacked with what else to pre-occupy themselves. The fellow students who did not wish to join the group in the Square, therefore, had no alternative but to go back to the halls of residence or, if they were NRs, to leave campus. The recalcitrant chaps were probably taking their practicals on how to win concessions from the government of Dr Obote but they were doing so as if they wanted a strike to be sustained, the university closed and some of us get away without any evidence of what we had struggled to come to Makerere Hill for. That was unacceptable to Rutakingirwa and myself.

The Campaign occurred in the context of mistrust between the Makerere UPC Branch and the Student Body

To be fair to the Ogenga Otunnu group, they had other genuine reasons for mistrusting both the university party branch and NUSU. In Academic Year 1982/83, when we entered university, the Students Guild had been banned following chaotic election scenes between party candidate Welishe Watuwa on one hand and present New Vision columnist-cum-Canadian-based educationist Opiyo Oloya. Somewhere in the mix had also been Ndamirani Ateenyi, who I last heard of about ten years ago when he was in the Directorate of Public Prosecutions (DPP). That was even hardly a few months after the ban imposed earlier by Idi Amin was lifted. When the ban was lifted the ruling party branch moved in to ensure that only a candidate compatible with the GoU could stand chances of becoming Guild President. Party branch chairperson, (now Prof) Adipala Ekwamu, was lecturer in the Department of Agriculture and resident at the University Farm in Kabanyoro located in present day Wakiso (it was Mpigi then), but was heading a branch in Kampala due to lack of clarity on party structures in places of work. The vice-chairperson was Kefa Kiwanulka, then a Year 3 student (now PhD and Hon MP for Kiboga East). Adipala (we derisively called him “Adipork Ekworam”, partially in reference to pork and crude waragi which we called “quorum” although he reportedly never even partook any of them), therefore, found himself at odds with student leaders such as Student Representative Council (SCR) chairpersons Owiny Dollo Chigamoi (University Hall), Sam Kwizera Bitangaro (Northcote), Isaac Isanga Musumba (CCE and Old Mitchel Complex), Elel Obote (Nkrumah), all still prominent national leaders today, except Elel whom I have never heard of again after he retired as Principal of the Uganda College of Commerce (UCC) in Pakwach. After thorough screening, the university party branch insisted on clearing only (future Haji) Badru Ssebyala (most recently a Resident District Commissioner somewhere) for nomination to contest for the Guild Presidence in February 1983, leaving students, including Returning Officer Isanga Musumba, quite discontented. Part of the discontent was because Ssebyala was no ordinary university student, having trained at diploma level and taught at Kibuli SS in Kampala before gaining Makerere admission through the Mature Age Entry Scheme. There were also fears that since Ssebyala had a specific connection to Paulo Muwanga, the defence minister and vice-president of that time, he was coming to do Muwanga’s bidding. Among the discontented was Masaba who had been blocked from getting nominated but was, by turn of fortune, to later become NUSU national President.

After the perceived imposition of Ssebyala on the students, they (the students) now contrived to depose Adipala Ekwamu (from the minority Kumam ethnic community within Teso) when party elections came round in April of 1983. Respected fellow staff such as Dr Ben Kiregyera (now a globally renown statistics consultant) and Dr Kiboma Gimui (now retired and living in Bugisu) attempted to present themselves for election but they soon saw issues so messed up that they left them to students. And the dare devil we as students presented against Adipala Ekwamu was Lima lo Lima, the ever brief-case carrying, eloquent, bush-bearded Political Science and Public Administration Year 2 student in dark suits and matching neck ties. Lima lo Lima was from Atutur, also in Teso, so he could tussle it out well with Adipala Ekwamu, we thought. But that is how Otai also first entered our student politics, giving Lima lo Lima some small support against Adipala Ekwamu who had vast independent resources by virtue of being a senior academic as well as a businessman allegedly with transport interests. The campaigns were fairly smoothly but the polling process was chaotic, to say the very least, with Adipala Ekwamu winning (but he was also virtually the organizer of the polls, anyway!) while Lima lo Lima and several other students ended up in various police cells around Kampala overnight for allegedly attempting to rig. In the morning, however, late party secretary general Dr John Kidhiza Magoola Luwuliza Kirunda (also the Internal Affairs Minister) consulted Dr Obote and released the students without any charge.

The February 1984 elections, therefore, saw candidates distancing themselves from the ruling party. (Now Prof in an American University) Ben Ebil Otto clearly identified himself as a candidate of the DP, pulled great crowds, and displayed eloquence like I had never witnessed before on campus. Ogenga Otunnu, an Acholi like Ebil Otto, on the other hand insisted that he had independent resources (and political connections) to run the race without the meddling of the UPC branch. The branch, however, also insisted on supporting him and getting him nominated as its candidate. He won, anyway, but remained on a war-path with the ruling party branch till opportunity presented itself during the controversy over student allowances. Daily Monitor, a Kampala newspaper, has alleged, though, that Ogenga Otunnu also fell out with GoU over allocation of rations from army shop, pointing out that army chief of staff Brig. Smith Opon Acak had blocked an allocation of large quantities of stock from the shop to Ogenga Otunnu, thus his bitterness against the party and the government.

Okurapa’s regime marked one of the earliest times Police used teargas to disperse rowdy students

Faced with a rebellion that could have disrupted our studies, Rutakingirwa and myself worked with Okurapa to quel it (for which effort Ogenga Otunnu baptised us “Forces of Darkness”!). The Late Captain Kagata Namiti, then an influential Makerere alumnus and Member of Parliament (MP) representing the Uganda National Liberation Army (UNLA), was sent by Dr Obote to join our efforts. Captain Namiti came to Freedom Square on two ocassions to address and convince our striking colleagues to return to the lecture rooms as the government looked into our matters. When all efforts failed, we were only too glad to see Police bring in teargas to clear the Freedom Square. A few canisters of the gas were thrown around and everybody else scampered as Ogenga Otunnu was arrested. To the best of my memory, nobody died or was even seriously injured but, being what it is, the gas had caused enough tears to last a week or two. I need not point out here that beginning only a few years later teargas was ruthlessly replaced by live ammunition, killing some unfortunate students and injuring many more. Some of them met their fate while contesting the abolition, not just none increment, of the famous “Boom”.

I do not know where the Police took Ogenga Otunnu after the arrest although I seem to remember as if by close of day he had been chauffer-driven back to his hall of residence (Lumumba). In his book, however, he writes, “… thousands of my colleagues demonstrated their collective opposition to terror, intimidation, dictatorship and corruption in the government and at Makerere University. I thank them for their patience, resistance, solidarity and activism”.

He adds, “My fellow political detainees at the Central Police Station in Kampala in 1985 shared with me their tragic stories. Their humor, friendship and strength, in the face of protracted inhumane and degrading treatment, taught me how the country has maintained a semblance of sanity under intense and prolonged political terror and violence. Life in the prison of torture, humiliation and social death would have been unbearably traumatic without the prayers, love and encouragement of my wonderful parents, sisters, brothers, nieces, nephews and cousins. My friends, Colonel Kapuchu and Grace Kafura, smuggled in food, medicine and newspapers. May God bless them. My friends and colleagues from Makerere University, Okello Lucima and Ben Tumuharwe, with whom we were detained by the Obote regime, also deserve a word of appreciation for their friendship and courage”. I never before heard of Tumuhairwe, though, so I am not sure if he was part of that Political Science cohort.

With such political and military connections, the outgoing student leader seems to have known something about the impending collapse of the UPC Government at the time he steered the trouble while Rutakingirwa, Okurapa and I were not privy to any such secrets. And, indeed, the Obote Government fell to the Okello-Okello junta a month after my last paper. In the ensuing confusion some of the continuing students from western Uganda did not reappear as students at Makerere for almost a year, even then, many proudly as the former “bandits and bushmen” now serving in the NRA/M.

After Obote fell, I met Okurapa twice. The first time was deliberate, in his Mitchell Hall room in October, 1985 when I had returned to Makerere to pick my academic transcript in order to present a copy of it to the Ministry of Information and Broadcasting Services (MIBS) where the Public Service Commission (PSC) had just appointed me as Information Officer. I learnt that the junta government had a keep eye on him. If he missed lectures, they wanted to know what he was doing when he missed. If he went out of campus, they still wanted to know where he had gone and who he had met. He told me that even his failure to pick his food from the dining hall would be a cause for concern.

I next met Okurapa accidentally in April 1986, less than three months after the Okello-Okello junta had fled. At that time, not seeing many prospects MIBS, I was applying to Makerere for the post-graduate training as a teacher. I entered through the Wandegeya Gate, walked uphill past Mitchell and through the Faculty of Social Sciences then strutted (if you know how I walk!) along the tarmacked pedestrian way from the Arts Court to the Main Building where applications were submitted. He was coming out of Mitchell and heading for lectures at the Faculty of Social Sciences so we walked uphill together. This time, though, I was even scared of talking to him openly whether or not anybody seemed to be watching or listening in. Almost as expected, as soon as he wrote his last papers in June that year, he was picked and kept away from the public.

Writing in The Observer newspaper on January 7th, 2008, Okurapa gives a harrowing narrative of how he was arrested in the presence of Edidah (now his widow) and detained, first in Mbuya Barracks east of Kampala then rescued from there by Captain Namiti and brought to Army Headquarters at Republic House (now Bulange) where upon Captain Namiti arranging to release him, he (Okurapa) was rearrested. He writes that, soon after, Captain Namiti was himself arrested and perished in prison. In an exclusive interview with David Lumu, published in New Vision newspaper, the GoU-owned Kampala daily newspaper, on January 16th, 2022 (pp6&7), Okurapa also said he has, however, since met Gen Muntu and expressed his forgiveness.

Okurapa’s ancestry in Teso may have contributed to his exile

The Iteso have little linguistic relationship with us, the Bagisu/Bamasaaba whom they geographically engulf on several fronts. The Iteso, instead, have a closer ancestry relationship with the Karamojong and are, within Uganda, indigenous in the districts of Amuria, Bukedea, Butebo, Katakwi, Kapelebyong, Kumi, Ngora, Soroti, Serere and Pallisa. However, there are also some large indigenous Iteso populations in Tororo where their dominancy status conflicts with that of the Japadhola, a Nilotic community. Other Iteso indigenous populations as well exist in parts of Kaberamaido (Adipala Ekwamu’s ancestral district), Kalaki, Manafwa, Mbale, Namisindwa and Sironko. My Bagisu/Bamasaaba, on the other hand, are predominant in Bududa, Bulambuli, Manafwa, Mbale (both city and district), Namisindwa and Sironko.

Most of the Teso vegetation is tropical Savanah grasslands conducive for extensive cattle, goats, sheep, chicken or other animals and poultry. But the lands are only conducive to crops that must mature within three to six months in part owing to shorter rain regimes. The Teso crops include millet, sorghum, maize and other grains. They also have gram-peas and beans among the legumes, sim-sim and groundnuts among the oil seeds as well as sweet potatoes and cassava among the carbohydrates. The Iteso would traditionally sit down outside their grass thatched huts after a day’s very hard work in the gardens to sipping with long, wooden straws their frothy Ajon, a beer made out of millet and cassava or maize, play their akogo (a thumb piano) and dance with abandon.

Teso had a variety of fruits, too. Some colonial fellow had introduced oranges, tangerines, lemons and other citrus fruits as commercial crops so every traditional Iteso home had them – to be bought for a song or even picked for free. Moreover, the East African Railways and Harbours Corporation (EAR&HC), in building the 375 kms line from Tororo through Mbale (heartland of Bugisu) and Soroti (Teso) to Lira (Lango) and Gulu (Acholi) before Independence had in Teso also planted thick rows of mango trees on either side to supply biomass to the steam engine train anywhere it stopped. Those trees provided a very prodigious harvest of fruit at least twice a year and their seed was also dispersed by human factors into every homestead far and near the transport ways – if not to provide food then to provide shade under which the family would sit to sip Ajon as they happily played akogo and danced. Moreover, it was literally possible for boys and girls alike coming out of schools to climb a tree nearer the road and hope from branch to branch, monkeylike, eating fruit upon fruit along the rows of mango trees till they alighted, satisfied, at their homesteads a kilometer away. Besides, some of those Teso districts are near Lakes Bisina and Kyoga, joined by the Awoja river and pouring into the Nile, the world’s longest river. Agaria (fish) is, therefore, one of the abundant natural resources for the homesteads on the shores and the banks.

Unlike the Bagisu/Bamasaaba, the Iteso in addition used their animals to draw the ox-ploughs working their peasant gardens and polygamous wives to handle other tasks. Given such animal and human labour, they grew cotton, too, in more expansive gardens. Every village had its cooperative society store where to sell the crop for cash. The store was usually close to the venue of a weekly cattle market where to purchase household goods and – let us admit it – sip some ajon, happily play akogo and dance. At county level, there were as well ginneries to process the cotton into lint, fifi (for making the shrouds in which we bury our dead) and cotton seed for next planting season’s replication seed as well as for manufacture of soap, edible oil and animal feed. This called for establishment of local government administrative structures as well as trading centres and for security against theft of their animals. This security was guarranteed by more educated Iteso youth joining the Police Special Force in good numbers and the not so educated ones to almost certainly become part of the armed home guard militia.

They did not forget God either because they build humble structures to appease their spirits and where grew a place of worship there also grew an affiliated health facility to treat their physical bodies and an educational facility to sharpen their children’s brains. Ngora, in particular, was the prototype of this – with the Catholic church and the Church of Uganda (CoU), two teacher’s colleges each with its boys’ and girls’ demonstration schools, a private hospital with a nurses and midwives training school, a high school (which Okurapa and I attended), a school for special education, cotton cooperative structures, etc. If any of those was more than a kilometer away in the vast lands – that was no problem because the Iteso had enough resources to buy strong Raleigh or Hero bicycles that could be ridden by boy or girl, man or woman alike in search of the services. Admittedly, the bicycles were also used to fetch water from far away wells and swamps (obviously not very clean).

We Bagisu/Bamasaaba occupy higher grounds, in the volcanic mountains where coffee, matooke (bananas), vegetables and fruits ought to be aplenty. Our rainfall patterns are year-round like among the other Bantu areas in the equatorial zones further south-west but our population is so dense that there is little space for the cattle, goats, sheep, chicken or other animals and poultry Teso provided. Besides, either due to our less harsh climate or to our matooke culture or other factors, our physic is unmatched against that or the apparently tall, heavily built, relatively energetic Iteso. Our terrain does not even favour much the riding of bicycles and, in fact, it is taboo for women to ride them. Moreover, there have been years when the rains fail, such as in 1979/80, then our resilience gets tested beyond expectation as our bananas wilt, our coffee does not yield much and our entire socio-economic system exposes us to extreme vulnerabilities. That was the situation in Bugisu when in May 1980 I arrived in Ngora for my A Level. But I was astounded to find the Iteso still self-sufficient. For instance, the Iteso had had no reason for not sending their children to school because at the beginning of the term the parents just needed to sell one animal to cater for a child’s entire fees and other school or personal requirements.

Once I had settled in, I joined groups that excitedly made endless visits to the churches, schools, hospitals and a Thursday cattle market into which thousands of bicycles emerged from behind inselbergs. We climbed the inselbergs, too, especially Ogereger (so named because it was ful of lizards) which was right between our school and the Freda Carr Church of Uganda (CoU) Hospital and its nurses and midwifery training school. However, we also used to go visiting the homes of our schoolmates deep into the Ngora villages of Ajeluk, Tididyek and Nyamongo pertaking of their hospitality through food and drink till our stomachs felt like busting. Their marriage ceremonies, some of which we were even privileged to attend invited or uninvited, were still week-long fanfares during the dry season, where twenty or thirty heads of cattle were exchanged for beautiful, young brides. The more a man worked hard, the more cattle and other animals or poultry he accumulated and, therefore, the more brides the man would afford to marry with his cattle. The brides in turn contributed labour to his gardens, bringing in even more wealth.

All that ended in 1986 when life was disrupted by constant, unprecedented cattle rustling and murder of any resisting herdsmen by the Karamojong and their Kenyan Turkana relatives. The new NRA/M government, which had upon ascending to office re-absorbed the Special Force into regular, ineffectual police and disbanded the militias, yet it was seemingly not coming to their defence. To make matters worse, by then remnant forces of the UNLA had regrouped in Acholi as the Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) under Alice Lakwena and Joseph Kony and were pushing back towards Kampala through a now gloomy Teso. The Iteso were forced to flee from their prestigious homesteads to settle in the Internally Displaced People’s (IDP) camps surrounding the places of worship, educational facilities, weekly markets, health facilities, cooperatives infrastructure and weekly markets which were themselves facing the brunt of civil strife. The mango trees were in due course mowed down by some authority or other either to provide wood fuel in the IDP camps or to provent enemies from hiding in their thick foliage. Bicycles were confiscated in an effort to ensure that whoever hit the villages did not ride away too fast. If Teso had been as well built as the Gaza Strip in the Middle East at one point, everything in it would equally have been razed to the saddening ground by competing forces similar to Israel and Hamas within just months – and with each combating force piling blame on the other. Teso was within months becoming one unbelievably vast ghost jungle.

Pressed to the wall, the Iteso were to eventually rise up in arms, under the leadership of Otai and his rebel outfit called Uganda People’s Army (UPA) fighting the NRA/M on one side, the LRA on the other and the Karamojong/Turkana rustlers on yet another. There were also other Iteso rebel commanders such as one Jesus Ojirot and Musa Echweru. Young Iteso such as Lima lo Lima who were either not interested in taking up arms or took them up and lost battles too fast or did not know how to join the rebellion fled to exile, in his case going through Kenya and ending up in Australia. The scuffles climaxed in 1993 with the NRA/M rounding up over 60 Iteso, locking them in locomotive wagons at Okungulo Railway Station about 8 kms north of Ngora town, lighting a logfire underneath and slowly roasting the poor souls to death.

With time, however, the LRA and UPA insurgences were contained in Teso, Lakwena fled to Kenya and Otai sought asylum in the United Kingdom (UK). Ojirot was captured and executed against a Mvule tree which I have personally visited in Katakwi’s Usuk County while Echweru opted for peace and is now a minister in the Museveni cabinet. Kony, on the other hand, remained marauding in parts of Acholi till as late as 2006 when attempts to hold peace talks in Juba, the Republic of South Sudan (RSS) capital miserably floaped. Nobody knows where he currently is, if alive at all, but he was last heard of in the Garamba National Park of the Central African Republic (CAR). The International Criminal Court (ICC) has issued an international warrant of arrest for him. Meanwhile, Lima lo Lima died in Australia in the 1990s and his remains were brought for burial opposite the defunct cotton stores at Kapokina in Atutur, Bukedea district. Otai died in the UK during January 2020 and his remains were repatriated to an official burial granted by the GoU at Oderai near Soroti. Being still considered a desident, Okurapa did not travel to Uganda for either burial. Instead, he posted a colourful photo of the Otai funeral service on the Facebook wall and wrote, “In his death, Uganda lost a great son. Peter, may you continue to rest in Peace”.

Records are hard to come by as a few years after 1986 they were mostly burnt in a suspicious Republic House fire. Besides, for various reasons, I have not talked to Mugisha Muntu either to establish exactly why he held Okurapa. But my strong conviction is that the arrest, rearrest and detention without trial was intended to forestall the youthful Etesot (masculine singular of Iteso) leader’s participation in this then impending Teso Uprising under Otai. Much as the move could have been justified on those grounds, however, it does not warrant the torture to which he describes himself to have been subjected.

Okurapa’s family and work life

Okurapa’s late father, Hensley Ephraim Okalebo, was at the time of my studies in Ngora a magistrate in Mbale but later became a High Court Judge. While we were in Ngora with Okurapa, I visited the Okalebo home in Mbale and had memorable few moments with the tall, dark, slim cheerful old man who was, admittedly, too busy to spare me any more time. But I was to meet him again in Kampala and Mukono when he was judge, except that this time I mechanically interacted with him on journalistic issues rather than on casual, family matters. Characteristic of the traditional Iteso, at the time of his death and burial in May 2021, Justice Okalebo had to his record seven wives and thirty-two children. One of the wives, Esther, was Okurapa’s mother who had died earlier. Unsurprisingly, Okurapa attended neither of those funerals. A posting on Okurapa’s Facebook wall at the time of the memorial service for his mother in September, 2020, has a photo of a tiled grave with flowers and a telling message of appreciation, “What an emotional weekend! Thanks to my family at home for putting together a memorial service for my mother, Esther”. I have also read a Facebook posting about the death of his brother, David. Assuredly, OKurapa foresaw what was coming his way when he told The Observer newspaper on 7th January, 2008 that he could not come back home to bury his loved ones when they die.

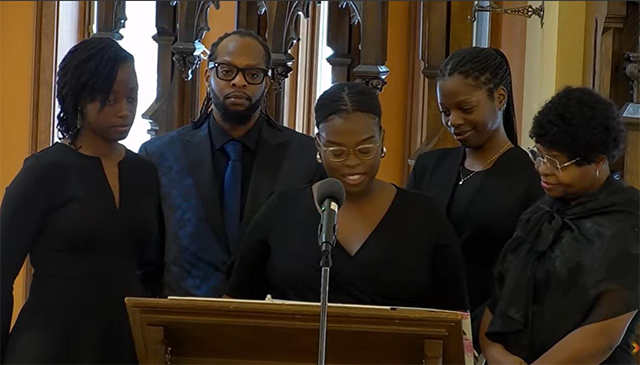

At the time of his own death, according to a Canadian website, Okurapa has left one wife Edidah (who had found a way of joining him outside Uganda) and four children named Peter (coincidentally or deliberately shared with Otai?), Esther, Faith, and Jeldin. Two of the children are working, after graduating from university, while two are still studying at York University, in Ontario. The website says in Kenya, Okurapa and Edidah came across advertisement regarding the Canadian federal immigration program “…and thought that Canada would be a good choice for his family” despite the reputed cold temperatures there. The family was to face the brunt of those diametrically extreme temperatures when they arrived in Toronto in March of 1989. That must have been because even this week a passenger plane flipped on the runway at Toronto’s Pearson International Airport due to bad weather.

Okurapa is said to have got a job as a Manager at the Factory Carpet Operation and, indeed, in my earlier communications with him he said he was a Carpet Floor Manager (but explained no further). The website says he stayed in the carpet business for two years before joining City of Toronto where he rose through the ranks to become Community and Labour Market Manager. In that capacity, he worked “with the City’s employers to determine their labour market needs and helps to match employers with employees to suit their business purposes”. However, apparently he kept one foot in a now private floor carpet business.

One thing Okurapa never forgot while in exile was his Iteso ajon, come winter, come summer. One of his Facebook postings shows him sitting at home on the 150th Anniversary of the founding of Canada, sipping some frothing stuff from a jug. In the absence of the long wooden straws, he improvised plastic tubes. I hope he also had akogo to play and dance to when stuff evaporated from his stomach to his head.

Okurapa was out of Uganda but not out of Uganda’s politics

I first heard Okurapa on the British Broadcasting Corporation (BBC) Focus on Africa bulletin a few days after his arrival in Kenya. Apparently he had timed when the NRA/M were busy making preparations to celebrate their second anniversary in power and escaped in the confusion. But he says when he rang Dr Obote to narrate the humiliating conditions under which he had been held at Republic House, the twice deposed former president advised him that Kenya was not safe enough for a Ugandan exile. Then he writes that, as Dr. Obote had predicted, life in Kenya became tricky for many Ugandan refugees.

“Time and again, the Kenyan security would round up Ugandan refugees and some got deported to Uganda. The NRA agents that Obote had spoken about were also many in Nairobi and it was no longer safe for many of us,” he writes The Observer on January 7th, 2008.

“At the same time, Museveni was putting pressure on the Kenyan government to have some of us deported. Kenya was increasingly becoming unsafe and it was time to look elsewhere for refuge. With the help of the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR), I relocated to Canada on March 1st, 1989,” he adds.

Delving into the bitter-sweat life in Canada, he says, “It took us a while to adjust to life in Canada. The winters are very cold and the summers are very hot and humid. Despite all this, Canada has been nice to me and my family and we have made it home. It is a home far away from home. Life in exile is truly tough”.

He had a decent job, he says, and lived a modest life with his family but again adds, “Several of my loved ones have passed on, including my father and in-laws, and yet I have not been able to go back to a country I fled from to bury (them)”.

“This is the painful part of exile life. But I will always remain grateful to Canada for welcoming me and giving me the opportunity to raise my family in an atmosphere where true peace and justice prevails,” he points out.

My purpose for remaining in communication with Okurapa had nothing to do with his work or family life in Toronto, though. Instead, I sought to be updated over the affairs of UPC. Even when I lived on the Zambian Copperbelt as an expatriate teacher between May 1994 and November, 1997 and in Lusaka’s Hubert Young Teachers’ Hostel for another year after the Copperbelt, it was easier for me to get updates from Okurapa thousands of kilometres away than from Obote’s residence in the Kabulonga suburb of Lusaka. When technology became available, Okurapa created the party website (https://upcnet.com) and my duty when I did return to Uganda as a journalist was to pick information from the website regarding Dr Obote and the party, cross check for further details from its creator and from the party headquarters at Uganda House in Kampala, then craft stories in New Vision.

Around 1997, Dr Obote decided that it was time to begin the process of re-establishing the party structures by putting in place a Presidential Policy Commission (PPC). He appointed former NUSU leader and culture minister Dr James Rwanyarare as the PPC chairperson and then Makerere University non-academic staff Henry Mayega (who was recently a diplomatic staff in the United Arab Emirates) as vice-chairperson. Others on the PPC were Okurapa, party lawyer Peter Walubiri, former agriculture minister Samwiri Mugwisa and his state minister Patrick Rubaihayo (RIP), then former Clerk to Parliament Edward Ochwo, Makerere University Zoology lecturer Oweyega Afunaduula, former Uganda Development Corporation (UDC) managing director Chris Opio, Haji Badru Wegulo and Canon Andrew Nyote (RIP), a former security operative. Among others were former Bungokho County (Mbale) Constitutuent Assembly Delegate (CAD) Engineer Darlington Sakwa, who has since quit elective politics. Also included was Ahmada Washaki, who in due course joined the NRM and is now Resident City Commissioner (RCC) for Masaka. Dr Obote may not have been successful in balancing the gender on the commission, though, as I remember seeing only one woman on the Commission whose name I can hardly even recall. Alice Alaso Asianut, the Serere Woman MP of that time, has said she was also actually appointed but turned down the appointment.

If you think that working remotely is a Corona Virus Disease 2019 (Covid19) innovation, you may need to rethink again because I first interfaced with it through the PPC. Okurapa would sit out there in the safety of Toronto at the time when party activities outside party offices were probited and set up machines for Obote in Lusaka to teleconference with the rest of the PPC at Uganda House. That is how arrangements were eventually made for Dr Obote’s son Jimmy Akena to return from exile and take up the leadership mantle when some restrictions were lifted. Okurapa remained in contact with Dr Obote till his (Obote’s) death in October 2005. Of course he could not come for the burial. So, yes, Okurapa was out of Uganda, missed the opportunity to bury Lima lo Lima, his (Okurapa’s) father, his mother, his brother, Otai and Dr Obote but he was not out of Uganda’s politics.

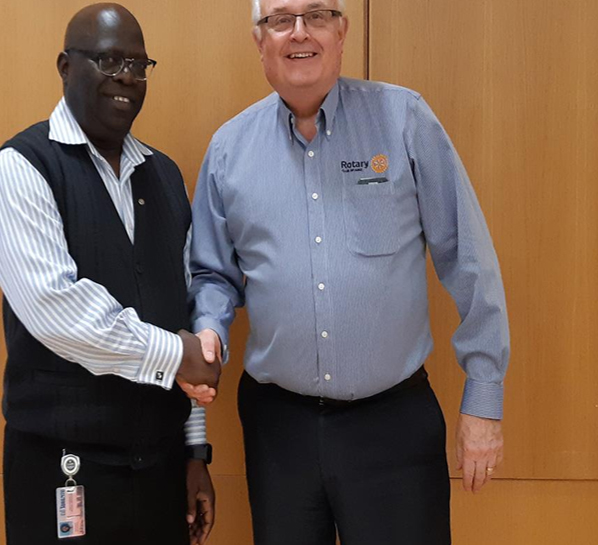

Okurapa the Academic, Social Worker and Rotarian

In Canada, the website says, Okurapa was also a lecturer of Canadian Social Policy at Seneca College and a member of the Board of a Ugandan Relief organization. Another Canadian website says Okurapa was, “…a proud Rotarian and past president of the Ajax Club (in Ontario). Despite being a member for just over four years, George’s commitment to the principles of Rotary was evident, earning him the Paul Harris Fellow Award – the highest form of recognition given by the Rotary Club of Ajax. This award was a testament to his exemplary efforts, sacrifices, and dedication to service both locally and internationally”.

The website says, “He was a man whose footprints were left everywhere he walked, both literally and figuratively. His infectious smile, boundless energy, and positive spirit lifted the hearts of all those around him. Whether through a kind word, a shared laugh, or simply being present, George had a remarkable ability to connect with anyone. His unique blend of humor, compassion, and wisdom made him a beloved figure to all”.

At the time of death, he was sourcing medical equipment for Soroti Regional Referral Hospital

The Rotarian was sourcing medical equipment for Soroti Regional Referral Hospital. Speaking during a virtual funeral gathering, Prof Francis Omaswa, a renowned African medical practitioner and relative, said that Okurapa had so far sourced one container of equipment and was waiting to fill the other container before he could ship them together to Soroti. Martin Osengor, another relative who is a logistician based in the United Kingdom (UK), confirmed that Okurapa had asked him to sort out the transport arrangements for the equipment. The mourners were, however, assured that the death would only delay but not halt the delivery of the equipment to Soroti. Patrick Aeku, a Canadian trained medical practitioner who helped develop specifications for some of the equipment, has also assured the mourners that Okurapa’s initiative will be followed up and fulfilled.

As Charles Opolot, a communications professional related to Lima lo Lima by marriage and coordinating media coverage for the Okurapa funeral, has noted, “Okurapa was a charismatic leader. He was our mentor. By listening to his oratory, we can judge that he represented the voice of reason and progress. Personally, I never met him but Lima lo Lima used to mention his name whenever he wrote back to us from Australia. The two were our role models and we shall endeavor to carry on their legacy in order to again place Teso in the socio-economic dynamics of this country”.

On a superstitious note

The Iteso and other Africans believe that a famous person does not die alone. In the case of Okurapa, Mzee Wilson Angura Okello, a young brother of Okurapa’s late father Justice Okalebo, died about three week after the death of Okurapa was announced. Mzee Okello is father of Dr James Onyoin Okello, Chartered Public Accountant (CPA), who is also a pioneer Hass avocado farmer in Bukedea. Some funeral arrangements for Okurapa, therefore, had to be paused as those of Mzee Okello were fast-tracked. He was buried on Saturday, 15th February, 2025 at Koena Village, Kachumbala in Bukedea district. So, it has been quite some weeks of mourning!

Funeral arrangements for Okurapa’s Remains

A memorial service for Okurapa was held at 11:00 AM on Saturday, February 8th, 2025, at St. George’s Anglican Church, 77 Randall Drive, Ajax. In lieu of flowers, the family requested that donations be made in his memory to the Rotary Club of Ajax. Another memorial service was held at the All saints Cathedral in Kampala today, Thursday, 20th February at 9am before the cortege left for Bukedea. Yet another service will be led by Rev Captain George Olaboror at St Andrew’s CoU in Kachumbala at 9am tomorrow, Friday, 21st February. This will be followed by a night vigil at the ancestral home in Komuge where the final funeral service and burial will be led by Kumi Diocese Bishop Michael Okwi Esakan on Saturday, according to a notice posted by Osengor on a forum created specially to coordinate the functions.

Fair thee well, George Okuraption, sorry, Okurapa, the young man who unenviably transited the Makerere University Guild through three heads of State punctuated by two military coups and unprecedented confusion! Those that labeled you, Rutakingirwa and myself as “Forces of Darkness” probably did not fully fathom what was at stake. Farewell, Son of the Iteso! Farewell, my fellow Ngora High School Alumnus!

******

The author is Founding Director of Vicnam International Communications Ltd, a private firm of communications, public relations and information management consultants. He specializes in the Proofreading and General Editing (PAGE) of documents and can be contacted by Tel: (+256)752-649519 and by Email: agmusamali@hotmail.com.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price