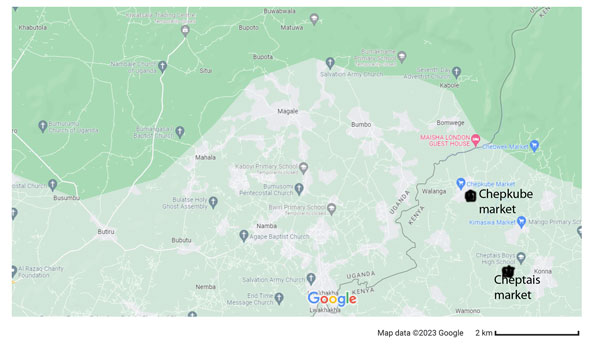

COMMENT | Alfred Geresom Musamali | The trending of former journalist Agnes Nandutu on social media this month reminds me of the late 1970s coffee smuggling through Chepkube and Cheptais sokos (markets) on the eastern side of the Uganda-Kenya border in the East African Community (EAC) (See Google Map).

The two sokos , along with two others called Chepiungu and Kapchanga which I have been unable to locate on today’s map, were the main outlets for Uganda’s Arabica coffee at the peak of the magendo (intense coffee smuggling) period of 1975 to 1979. By then, the Agnes Nandutu trending, was not one of the current dual (along with her senior sister Gorreti Kitutu) Bamasaaba Honourable Members of Parliament (MPs) that double as ministers for Karamoja in the Uganda Government who has, in Nandutu’s own words, “been baptised by fire” over some comparatively overblown government roofing sheets scandal. Instead, the other one was a young, beautiful, industrious Umubukusu housewife who mysteriously disappeared near one of the four markets and has never been seen again despite pleas from her husband and children as well as their relatives and friends.

The Babukusu (sometimes derogatively referred to as Bakitoosi) are Bamasaaba on the Kenyan side of the border and, except for a mix with some Kiswahili words here and there, speak the same Lumasaaba, share the same names and undergo the same circumcision rituals as the Bagisu (Bamasaba in the former Bugisu district whose main city is Mbale in Uganda). The ancestral lands of the Babukusu stretch from parts of Usian Gisu county (around Eldoret), through Bungoma county, Trans Nzia county (around Kitale) and, maybe, parts of Kakamega (around Webuye).

The less adventurous Bamasaaba of those days were known to roam around the said ancestral lands on both sides of the border but the more adventurous ones could also reach places as far as Soroti, Tororo, Jinja and Kampala in Uganda as well as Kisumu, Nairobi and Mombasa in Kenya. So, to send his message far and wide, the persona of Nandutu’s husband (presumably played by Wanyonyi wa Musungu) took, not to Twitter or Tictok or other modern technological tools, but to a guiter through whose sharp-stringed rhythm he lamented her departure. He sang:

Agnes Nandutu yaya, siaba sina;

Agnes Nadutu yaya, nukobol’engo.

Wandekhela babana bakali, siaba sina;

Wandekhela babana bakali, n’ukobol’engo;

Wandekhela tsingunyi tsingali, siaba sina;

Wandekhela tsingunyi tsingali, n’ukobol’engo;

Basaali boowo bareba, siaba sina;

Basaali boowo bareba, n’ukobol’engo….

Literarily translated, the person was wondering what had happened to Agnes Nandutu so that she could abandon him in solitude, with many childred and very inquisitive parents. He sang the lines in couplets (twos), with the end of the first line questioning what happened ( siaba sina? ) and the second line pleading that his wife returns home (n’ukobol’engo ).

Roofing Sheets in Abraham Manslow’s Hierarchy of Needs

In his hierarchy of needs, Abraham Manslow (1908 to 1970) points out that when man is seeking to satisfy himself he starts with physiological needs such as food, clothing and shelter, then moves to safety such as job security and progresses to love and ends up with seeking to belong through friendship, eventually getting to esteem and self-actualisation. The Bamasaaba on the Uganda side were in the 1970s not any different.

Located on the south-western slopes of Mt Elgon that towers astride the border, they had had a prosperous economy founded on coffee, cotton (in the lower belt), bananas, vegetables, fruits, cattle, goats and poultry till General Idi Amin arrived on the scene in 1971 and started turning tables upside down. Their geese that laid the golden eggs were the primary cooperative societies at the grassroots, Bugisu Cooperative Union (BCU, for coffee) and Masaaba Cooperative Union (MCU, for cotton) at the district level and the marketing boards at the national level. Some societies, unions and boards even directly or indirectly dealt in grains such as maize and legumes such as beans and animal products such as hides and skins by virtue of hosting on their premises butchers, tailors, shopkeepers and other service providers. Themselves and their neighbourhoods were the conveyor belts not only through which the cash crops were received, processed and exported but also through which construction materials, farm inputs, household commodities and a few luxaries such as beer and tobacco reached back to the farmers. Their business was everybody’s business.

For instance, it was the business of the school headteacher to know when farmers had delivered their cash crops to the societies. The farmers would simply present delivery slips at the school and their children would be allowed to attend school and even eat meals. The day the society’s cashier brought back funds to pay for the raw materials already supplied, the school headteacher ensured that that the farmers passed via school to clear their children’s dues. That was also the day when butchers (sometimes tenants of the cooperatives) made a killing out of selling meat and, thereafter, hides and skins. That day, too, was a Christmas come early for the tailors as farmer’s wives and children took measurements for new clothing. It was, as well, the day for the farmers to head to the bars for eating, drinking and dancing sprees, but, for most, not before they have passed via the local shop to buy household items such as sugar, salt and soap. Some of the music they danced came from Wanyonyi wa Musungu or Lawrence Barasa or other Babukusu while the subject of the music was about women such as Agnes Nandutu.

However, when Amin’s Economic War began to bite, farmers stopped receiving back any gains from the value chains, thus students fell out of school for lack of fees, teachers abundoned class due to the weightlessness of their pay, butchers could sell neither meat nor skins and hides, tailors had no meausrements to take and there reigned general economic chaos. Then, out of the frastration, some ingenuity of informally trading in the raw materials across the River Lwakhakha (the name itself means border in Lumasaaba) that marks that part of the Kenya-Uganda to the markets in Chepkube, Cheptais, Chepiungu and Kapchanga developed. With a bit of luck, anything could go across but the main items in demand were coffee, cotton, skins, hides, maize and beans and poultry.

First timers in the Trans-Lwakhakha informal cross-border business also known as (aka) smuggling or magendo usually came back with the basic items in Maslow’s hierachy of needs. Those included roofing sheets, sponge mattresses, Raymond blankets (from a factory near Webuye), tetron fabrics (clothing made out of some percentage of the same cotton we were smuggling away, mixed with polyester and some petroluem products) and Bata shoes (also probably from the same leather we were smuggling away).

Others were Tip Top (sliced bread packaged in a crackling half-paper half-plastic wrapping), Blue Band magarine (in the original tin with a boy’s photo on it), pyramid-shaped Kenya Cooperative Creameries (KCC) milk packs, sugar (from Mumias in present day Kakamega county, our own in Kakira and Lugazi by then having been hopelessly mismanaged and renovated almost a decade later) and salt (from Lake Magadi, again our own Lake Later Salt Works in Kasese having been run down but to date never renovated!). There were also Tree Top (a honeyed soft drink which consumers had to mix with some water in order to bring down the sweetness to manageable levels) which, some say, if you insisted on drinking undiluted went right through your digestive system and uncontrollably came out when least expected. They also brought Sportsman_cigarretes and _Pilsner beer as well as tooth paste andpowder soap (which, whatever the brand, we conveniently referred to as Colgate and Omo). However, as individual smugglers climbed up Manslow’s pyramid, they started coming back with Seiko or Oris analogue watches (complete with nobs which if you did not remember or know how to rewind in the evening made you wake up to a wrong time the following day) and Phillips or Sanyu record players.

Naturally, in order to make the record players functional, the international cross-border traders had to also bring Eveready dry batteries and vynil records (including of Babukusu music). And, yes, one of the most popular vynil records was about the dilemma Agnes Nandutu had left for her husband and children as well as relatives and friends. The other was in aclamation of the chaos in Chepkube and its sister markets:

Chebkube, isoko ya magendo oho!

Chepkube, isoko ya magendo…

(There were, in addition, other varieties of music, especially from the Dholuos such as Oluoch Kanindo)

But by then Amin had already posted anti-smuggling unit soldiers along the entire border, from the source of Lwakhakha high up in the mountains to down in the wetlands of Majanji on Lake Victoria, to prevent magendo. The soldiers grabbed those hard won items from the poor chaps, either during the crossing into Kenya or during the return into Uganda, making many a would-be smuggler arrive back home with only backet-loads of tears. Often they killed in order to take away the items, if the so called smugglers insisted on not throwing the items away at the sound of bullets. While some confiscated items initially became property of the Amin government, in due course the soldiers whether on duty or not, and various masqueraders, used guns and all sorts of other explosive devises to threaten the smugglers before taking over the items for personal profit.

Lawrence Shisokho and Pascal Mandali Join the Cross-Border Trade

By 1977, Uncle Lawrence Shisokho from our Banambutye clan of Nabumali Town Council as well as Busoba and Nyondo sub-counties in Mbale district had been forced by circumstances to join the cross-border. He had only a few coffee bushes really, next to his two roomed mugongo ggwa mbwa (simple design) house with hardly ten (10), rusty roofing sheets on either side. The house was on the left side of the road between the Holy Trinity Church at Nabumali and Nyondo Teachers College, about a hundred metres after where eventually Nabumali Secondary (not High) School was built. Uncle Lawrence’s more prosperous brothers, George Mandali (RIP), Davis Wekesa (Hitler, RIP) and Edward Masette lived on the right side of that road. He used to pick his coffee, take it to the pulpery, dry it and eventually carry it almost fifty kilometres on his head to Chepkube or one of those other three markets. He had three or four teenage children of approximately my age in that home and you would wonder how they all fitted into the tiny structure at night. I remember that two of those children were at secondary school and Uncle Lawrence must have been struggling hard to even equip them with scholastic materials and pocket money.

The prospects of earning any coins at all may have attracted my cousin, Pascal, son of Mandali to join Uncle Lawrence in smuggling. Some people claim, though, that Uncle Lawrence actually convinced or coerced Pascal, who had, incidentally, lost his sister Rose Mary two years earlier and their grandfather Yoweri not much earlier, to carry some of his baggage so that he (Uncle) gets adequate cash to buy and return with roofing sheets for expansion of his humble house. Others say that Pascal, a twelve or so year old pupil of St John Bosco Nyondo Demonstration School, himself insisted on going along with Uncle Lawrence because he needed money to buy scholarstic materials. So, Pascal, obviously yet to be circumcised, carried half a tin (10kgs) of coffee as Uncle Lawrence a full tin (20kgs). Those who went in that entourage claim that at first they progressed well as they went passed Nyondo, climbed into the pebbly outcrops of Lukaka at that time still full of Napuru (antelopes), overlooked Mayenze and Bubulo Corner (part of the current Manafwa Town Council) and crossed the Mbale-Bududa Road at Buwakoko before following the foot of Namisindwa ridge towards Bukhaweka, Bupoto (just south of Matuwa on the map) and Bumbo. But by the time they reached Bumbo, Pascal is said to have been extremely tired. Uncle Lawrence is believed to have urged the boy to end there, sell his coffee and go back home. But Pascal, having come all this way, persisted towards to the last mile stretch. I can still tearfully imagine Pascal panting, sweating, climbing a hill here, sloping down a slippery valley there, skipping over a fallen colleague then himself falling, getting up without cleaning the mud off his clothing but trudging to the beat of those Babukusu vynil record aclamation of the chaos:

Chebkube, isko ya magendo oh!

Chepkube, isoko ya magendo…

Then as they crossed the Lwakhakha river, which is a very small but very swift stream up there, into Kenya, they fell into an ambush. Pascal was hit by a bullet, fell on the banks of the river and started bleeding. Uncle Lawrence reportedly tried to save him but realised they were now both going to fall into deeper trouble as the persons who had shot the bullets were marauding in the bushes, waiting to pounce and take the commodities. He scampered, luckily with his baggage, as the boy behind was shouting, “Uncle, do not abandon me”.

Uncle Lawrence believed that he would be of better assistance to the boy if he unbuddened himself of the coffee, put some money in the pocket and hired helpers to come and carry Pascal to wherever they could get medical attention. On making the sale and returning to the scene of the ambush, however, he found the boy had been pushed further into the river, presumably by the thugs, and been swept away by the swift water currents. Needless to say, his coffee had been taken. After searching for days and not locating the remains, Uncle Lawrence came back to Banambutye and reported the development. Mandali’s older son, Sergeant Emmanuel Musamali (not my brother by the same name), came all the way from his duty station in Karamoja to collaborate with the army on the ground in searching for Pascal but to no avail. Bitter accusations and counter-accusations rent the air amongst our Banambutye families over the matter. Before long, unfortunately, Emmanuel was killed in the clashes that either led to or followed the overthrow of Amin. We have never traced his remains either. Then in 1986, as we were getting over the foursome grief (of Yoweri, Rose Mary, Pascal and Emmanuel), Uncle George himself died, without an iota of information about where the bones of his two sons rested. As if that was not enough, Uncle Lawrence was to die in a granade explosion hauled into the bedroom of his rusty roofed tiny house in 1988 during the confusion that followed the overthrow of the Second Dr Apollo Milton Obote government. Thrown through the window, the granade tore through Uncle Lawrence’s bed, shreaded to pieces parts of himself and his wife who was sharing the bed with him, and exit through the roof, mangling the rusty roofing sheets.

So, towards the end of the millennium, as we Banambutye continued puzzling our heads over what we could do to trace the bones of relatives, Babukusu were also still singing about the disappearance of Agnes Nandutu:

Agnes Nandutu yaya, siaba sina;

Agnes Nadutu yaya, nukobol’engo….

The difference is that this time we know where our Agnes Nandutu is. She briefly went undercover (allegedly by skipping the border into Kenya) then reappeared and handed herself to police investigating the roofing shits (sorry, sheets) saga. And as she was smilingly being led away, she even bid us farewell, Lala style in the Teletabbies television series, “Bye bye!”. But even if she is absolved and return to represent us in the August House again, we shall still take long to fully comprehend the ominous and treacherous confusion into which the government sheets have sucked (pun intended) her.

Meanwhile, for The Independent online, this is not Aaaagggnnneeess Nnnnaaannndduuutttuuu, reporting from Lwakhakha, Uganda.

*******

The author is Founding Director of Vicnam International Communications Ltd, a private firm of communications, public relations and information management consultants. He specialises in the Proofreading and General Editing (PAGE) of documents and can be contacted by Tel: (+256)752-649519 and by Email: agmusamali@hotmail.com.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Beautiful and informative piece of writing.

Great information. Agnes and Gorreti must read it. All noted with thanks.

Brilliant piece of article

Accurate about the magendo and markets for coffee across the border. Then coffee was simply known as kase.

Wanyara naabi papa

This a wonderful piece of information by far.

Thank you.