The last president of apartheid South Africa was driven to end it by pragmatism, not idealism

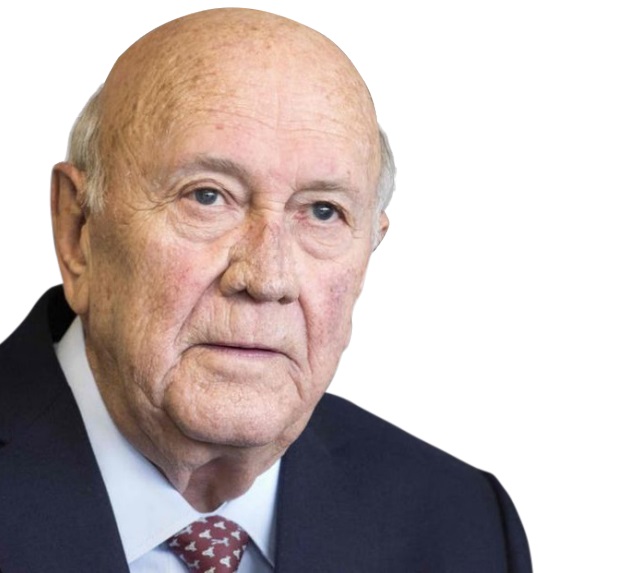

| CHRISTI VAN DER WESTHUIZEN | Few recent historical figures in South Africa provoke more divergent views than Frederik Willem (FW) de Klerk. He was president of the country from 1989 to 1994. Some will remember him as the last white South African president who played a primary role in ending the brutal system of apartheid and preventing further bloodshed. But, many will remember him simply as the last white minority leader to preside over apartheid and the violence that upheld it.

In recognition of his role in the demise of the formal apartheid, De Klerk was awarded the Nobel Peace Prize in 1993. He received it alongside Nelson Mandela, who became South Africa’s first democratic era president a year later. Historians have pointed to the white minority’s unusual capitulation of power, especially when gauged against other settler societies. De Klerk arguably had an important hand in that.

But Mandela’s disparagement of De Klerk a few years prior as the “head of an illegitimate, discredited minority regime…incapable of upholding moral standards” captures not only the animosity between the two leaders, but the feelings of many if not most South Africans.

That De Klerk never saw himself and the National Party regime in that light, is paradoxically what enabled him to lead the party’s relinquishing of state power.

Not that he had set out to do that.

The end of the Cold War with the dismantling of the Berlin Wall in 1989 meant the loss of Soviet Union support for the anti-apartheid organisations. It also ended the West’s need of the apartheid regime as proxy in Africa.

Sanctions, the costs of military action in the southern African and an unabated popular insurrection pushed South Africa into an economic crisis.

Meanwhile, apartheid lost its hegemonic hold on Afrikaner intelligentsia, business, media and the churches as doubts grew about its morality and continued practicability.

Committed apartheid ideologue

De Klerk will be most remembered for his famous speech delivered on 2 February 1990 in which he announced the unbanning the African National Congress (ANC) and other liberation movements. But it should not be read as a Damascene conversion to the principle of black majority rule.

Rather the announcement was made by De Klerk the pragmatist. He was taking a strategic risk to regain the initiative, in a situation where the options beyond intensified military repression were rapidly shrinking. De Klerk seems an unlikely candidate to have led this process.

Born on 18 March 1936 in Johannesburg, he came from a lineage of leaders of the National Party. The party came to power in 1948 brandishing its policy of apartheid. De Klerk’s uncle, JG Strijdom, was the second apartheid prime minister. His father, Jan de Klerk, served as a cabinet minister under three apartheid prime ministers.

De Klerk was associated with the conservative wing of the National Party. He was active in Afrikaner nationalist organisations from a young age, before joining the apartheid parliament in the early 1970s.

De Klerk’s political career confirms his commitment to apartheid. After ascending to a National Party ministerial position in the late 1970s, he passed through portfolios instrumental in the domination of black people.

As minister of education between 1984 and 1989, he was the political principal responsible for the continuing implementation of “Bantu education”. This system was most devastating; enforcing the racial hierarchy through the limitation of black people’s life opportunities from an early age.

De Klerk clung to the view that apartheid was intended to address the complexity of South African diversity. In his statement before the Truth and Reconciliation Commission (TRC) in the late 1990s he protested the international assignation of apartheid as a crime against humanity in 1973. The Truth and Reconciliation Commission had been created to examine human rights abuses during the apartheid era.

He insisted before the Commission that crimes against humanity have to do with the “wilful extermination of hundreds of thousands – sometimes millions – of people” and that white people, in contrast, had increasingly shared state resources with black people in latter years of apartheid.

De Klerk’s position had not changed in 20 years, as evident in his 2020 public statement when he repeated this stance. But after an intervention by the Desmond and Leah Tutu Foundation, he backtracked a few days later and acknowledged the Rome Statute of the International Criminal Court’s definition of apartheid as a crime against humanity.

Nevertheless, his concession was ambiguous: “ this is not the time to quibble about the degrees of unacceptability of apartheid”.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price