The future of HIV/AIDS in Uganda

Uganda’s response for the next five years is anchored in the global attempts to realise a 90% reduction in new adult infections, zero new infections among children, 90% reduction in stigma and discrimination faced by people living with HIV, and 90% reduction in AIDS related deaths.

Indeed the national HIV/AIDS Strategic Plan 2015/16—2019/2020’s goal is geared towards zero new infections, zero HIV and AIDS-related mortality and zero discrimination.

Denis Odwe, the executive director of the Action Group for Health, Human rights and HIV/AIDS in Uganda (AGHA-U) says when HIV prevalence fell almost a decade ago; it was a result of several communication campaigns focusing on the ABC model. “That seems to have waned a bit in recent years.”

Odwe told The Independent recently that the government and other stakeholders need to focus their HIV prevention interventions on key populations that are contributing mostly to the new HIV infections. He adds that it would also help if the right agencies were used to target the key populations.

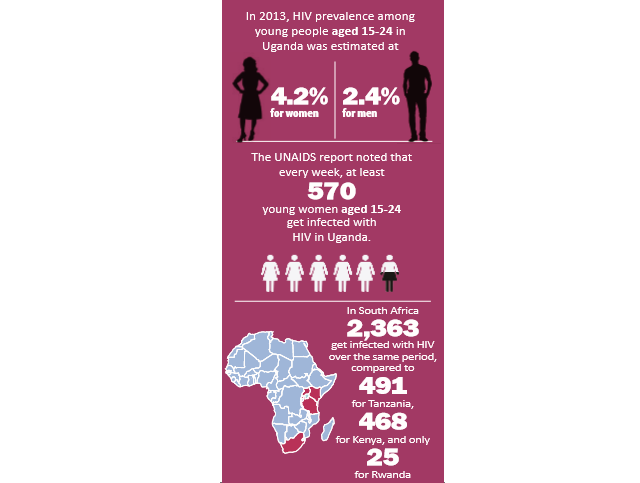

But Tumwesigye told The Independent that it is not true that the government has, for instance, neglected the 14-24 age bracket. He says the interventions that could be effective for this age bracket are not easily implemented as is the case for babies and pregnant mothers.

In order for interventions to work for the youth, there is urgent need to change behaviour or identify those youth infected and provide them with youth friendly services including treatment.

“It is very clear that we have not been doing very well for programmes that promote behavioural change (abstinence, being faithful and even condom use).”

“We need strong youth programmes, especially school programmes and counseling programmes and yet not many international funders are interested in supporting these interventions,” he says.

He says the little money that is now available is for biomedical programmes and yet programmes like safe medical circumcision seem to have dropped in uptake in recent years.

Nakasi says there is need for the government to review their decision on comprehensive sex education in schools.

“I don’t know why it [sex education] has been pegged to promotion of homosexuality,” she said, “But unless this is reviewed, Uganda’s HIV fight is going to get out of hand.

“Our girls are not being exposed to the risks around them and we are not equipping them with information on how to protect themselves or even the prevention strategies that exist.”

Nakasi says Uganda’s HIV response has somehow neglected this age group.

“It is like pouring water in a basket with holes,” she says, “We have taken care of them before they get out of the womb but then we also need to take care of them when they become teenagers.”

Nakasi adds that the government and other stakeholders are still not reaching out to the men who are using the young girls.

“When you look at the government strategy, at the moment, the target is on pregnant women who come for antenatal care in health centres but the girls are sleeping with old men whom we are not reaching out to.”

“The focus is on the pregnant women and leaving out the vulnerable youth,” she says.

“At the moment, everything is on EMTCT (Elimination of Mother to Child Transmission) programme which actually is doing wonders but then why give birth to a safe kid only to see them get infected when they turn 14.”

But some experts on HIV also say ignorance and misunderstanding continue to undermine efforts to end AIDS. In the worst cases, discriminatory attitudes and behaviour are being facilitated by punitive laws and policies.

Odwe told The Independent that although the Parliament of Uganda passed the HIV Control and Prevention Act, 2014 which provides for positive attributes like reasonable care to avoid transmission, counseling and testing and medical practitioners mandated to take tests, this same law has some controversial clauses with the most contentious being the criminalisation of HIV transmission and mandatory HIV status disclosure.

He says such sections need to be repealed because they scare people away from going to health facilities to test and seek for treatment.

Odwe also adds that funding from Uganda’s development partners has been around 70% but fatigue seems to be setting in from the donors and the government now needs to fund the bulk of the HIV/AIDS programmes.

He says the National HIV/AIDS Trust Fund, which was intended to cover the gap, was supposed to have taken off in the 2015/16 financial year but it did not, owing to lack of regulations.

Tumwesigye who was the Minister of Health when the Fund was being proposed told The Independent that it stagnated mainly because there were issues on how it would be regulated and housed.

****

editor@independent.co.ug

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price