They may have transformed the Sahara from lush paradise to barren desert

Kampala, Uganda | DAVID K WRIGHT | Once upon a time, the Sahara was green. There were vast lakes. Hippos and giraffe lived there, and large human populations of fishers foraged for food alongside the lakeshores.

The “African Humid Period” or “Green Sahara” was a time between 11,000 and 4,000 years ago when significantly more rain fell across the northern two-thirds of Africa than it does today.

The vegetation of the Sahara was highly diverse and included species commonly found on the margins of today’s rainforests along with desert-adapted plants. It was a highly productive and predictable ecosystem in which hunter-gatherers appear to have flourished.

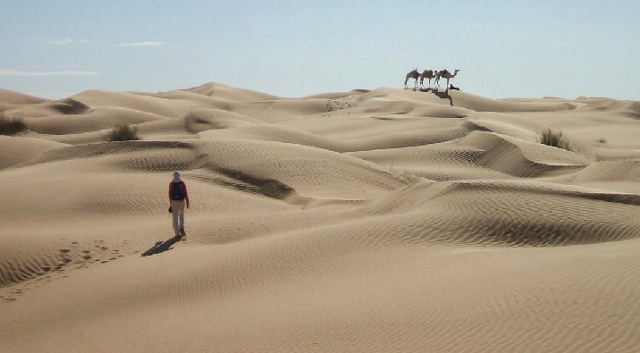

These conditions stand in marked contrast to the current climate of northern Africa. Today, the Sahara is the largest hot desert in the world. It lies in the subtropical latitudes dominated by high-pressure ridges, where the atmospheric pressure at the Earth’s surface is greater than the surrounding environment. These ridges inhibit the flow of moist air inland.

How the Sahara became a desert

The stark difference between 10,000 years ago and now largely exists due to changing orbital conditions of the earth – the wobble of the earth on its axis and within its orbit relative to the sun.

But this period ended erratically. In some areas of northern Africa, the transition from wet to dry conditions occurred slowly; in others it seems to have happened abruptly. This pattern does not conform to expectations of changing orbital conditions, since such changes are slow and linear.

The most commonly accepted theory about this shift holds that devegetation of the landscape meant that more light reflected off the ground surface (a process known as albedo), helping to create the high-pressure ridge that dominates today’s Sahara.

But what caused the initial devegetation? That’s uncertain, in part because the area involved with studying the effects is so vast. But my recent paper presents evidence that areas where the Sahara dried out quickly happen to be the same areas where domesticated animals first appeared. At this time, where there is evidence to show it, we can see that the vegetation changes from grasslands into scrublands.

Scrub vegetation dominates the modern Saharan and Mediterranean ecosystems today and has significantly more albedo effects than grasslands.

If my hypothesis is correct, the initial agents of change were humans, who initiated a process that cascaded across the landscape until the region crossed an ecological threshold. This worked in tandem with orbital changes, which pushed ecosystems to the brink.

Historical precedent

There’s a problem with testing my hypothesis: datasets are scarce. Combined ecological and archaeological research across northern Africa is rarely undertaken.

But well-tested comparisons abound in prehistoric and historic records from across the world. Early Neolithic farmers of northern Europe, China and southwestern Asia are documented as significantly deforesting their environments.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price