Gulu, Uganda | JULIUS OCUNGI | On a bright Sunday morning in Rwot Obilo village, Owor Sub-County in Gulu district, Justine Nantume, a small-scale farmer is busy weeding her one-acre rice garden, some 18 km outside the bustling Gulu city.

Adjacent to this rice garden is Nantume’s maize farm sitting on another three acres where a helper she hired is also busy weeding. Nantume recently acquired the land after relocating from Mukono district, in the central part of Uganda, and from it, she intends to earn money from her agricultural venture.

The mother of six children has been farming since 2008 and largely planted local maize seeds. A few years ago, Nantume however abandoned the local maize seeds for hybrids. She says the local maize seeds were no longer giving her the returns she wanted, took longer to mature, and were “susceptible” to pests and diseases.

Nantume has been relying on the Bazooka, Longe H, Longe 5, Nabe 16 Beans, and lately, the DK777 and DKD31 hybrid maize seed varieties, which she says gives an average of 1 ton per acre of land. However, for the yields to be successful, Nantume needs to accompany the seeds with fertilizer to boost crop nutrients and agrochemicals to fight pesticides and diseases and keep away weeds.

This farming season alone, Nantume has already spent 600,000 Shillings for 150 kg of Diammonium phosphate (DAP) fertilizer, 32,000 Shillings for buying two kilograms of DK maize seeds, and intends to purchase about eight liters of Weed Master each at 22,000 Shillings for killing the weed.

She has also spent over 500,000 Shillings in opening the garden using a tractor and paying for causal labor. Nantume admits that the farming costs are high but notes that she is motivated by the high yields from hybrids, which is good for business, unlike the traditional seed variety.

Although Nantume has been farming for close to a decade, she hasn’t been able to save her own maize seeds for farming in the next farming season. According to her, whenever she buys the seeds, she is advised to use seeds harvested for just one season and return to the shop for more new seeds.

“Those selling the seeds advise us that if you harvest the maize, you have to plant only one time then you go and buy new stock,” she says. Nantume is among a growing number of smallholder farmers in the Acholi Sub-region opting for hybrid seeds over local seeds as they seek higher crop yields for commercial gains.

Data provided by Integrated Seed Sector Development Uganda shows an estimated less than 15 percent of Ugandan farmers use quality seed which is mainly hybrid maize. Jacklyn Oryem, 38, a resident of Lamin Onami Parish, Lalogi Sub-county in Omoro District had been growing traditional maize, beans, groundnuts, and sunflower since 2012 but turned to hybrids a few years ago citing poor yield.

This season, Oryem planted DK980 maize seeds on a one-acre farm and the Aguara sunflower variety on a four-acre farmland, saying that they perform better than the local seeds. “I have three main reasons why I shifted to growing hybrid, first, it matures faster, they are tolerant to pests and diseases and gives high yield per acre after harvest,” She told URN in an interview.

Oryem however notes that while the seeds are commercially viable, they can’t be saved for the new farming season and notes that they are expensive. For instance, Oryem spent 120,000 Shillings after getting a 30 percent subsidy from the government to purchase four kilograms of Aguara Sunflower seed cost which cost 70,000 a kilogram in the market.

Agricultural experts in the region warn that the massive dependence on hybrid seeds by farmers and the constant tinkering with traditional seeds by seed companies is already affecting seed diversity leaving farmers unable to control their food system.

Jomo Oyet, the Omoro District Production Officer admits that local seed varieties are already on the verge of extinction as many farmers opt for fast-maturing and high-yielding hybrids. Oyet notes that the seeds on the verge of extinction are mainly maize and sunflower, which have gone through high levels of improvement and are mostly sought after by farmers in the region.

He says to make matters worse; the hybrid maize and sunflower seeds are not open-pollinated leaving farmers unable to save the seeds. Oyet however says with the growing population and demand for food, it’s unreliable to depend on local seeds for commercial agriculture arguing that it’s now a choice for one to choose either hybrid or local seeds. At least 60 percent of small-scale farmers in Omoro district have embraced improved maize seeds for agriculture while some 40 percent of commercial farmers are using hybrid sunflower seeds according to Oyet.

Despite these figures, some farmers in the region are sticking to local seeds and staying away from hybrid seeds and the use of pesticides in their farmlands. Juliet Adoch is one of the grassroots farmers in Gulu City who has been growing local seeds and practicing organic farming for the past ten years. Adoch has been using her backyard garden as a multiplication center for growing local groundnut variety at her home in Iriaga cell, Bardege-Layibi Division from where she transfers the seeds after harvest to her main garden.

She also grows traditional finger millet and cassava which she says is currently almost impossible to get. According to Adoch, traditional crops are not only long-lasting and resistant to pests, diseases, and climate change but also rich in food nutrients, unlike hybrids.

Farmers in a race to preserve local seeds

With local seeds on the verge of extinction owing to dependence on hybrids and the two decades of Lord’s Resistance Army (LRA) insurgency that affected farmers in the region from saving seeds, a group of farmers have joined hands to save their own local seeds.

About 20 km away from Gulu City in Tetugu Village in Ongako Sub-County, Omoro district, a group of farmers has established a community seed bank in a move aimed at saving endangered local seeds from going extinct and future usage. Ongako Community Seed Bank, the first in Acholi Sub-region was set up in 2017 and brings together over 20 farmers who are pushing to preserve and multiply local seeds in the community.

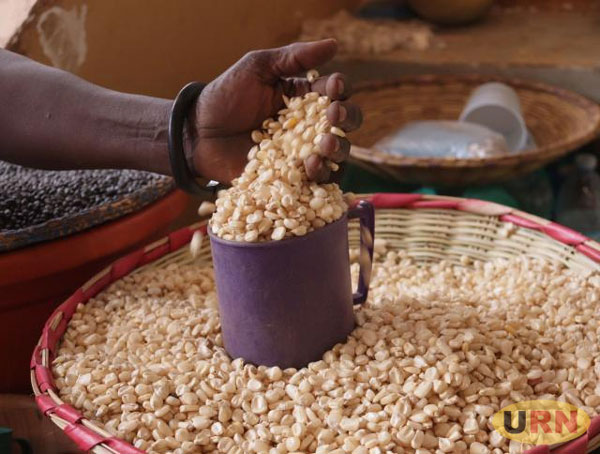

At the seed bank, the farmers are keeping local seeds that include beans, African Spider plants, black-eyed peas, cassava (Okonyo-leak), maize, okra, and pumpkin among others. Patrick Lakita, one of the members of the Ongako Community Seed Bank says the bank is important for the community to save the local seeds from varnishing owing to competition for hybrids. At the end of every farming season, Lakita and other members save about a kilogram of their local seeds, especially beans and maize at the bank which are sometimes given as seed loans to other farmers, sold and used in the net farming season.

“What we are keeping here is purely local, they are drought-resistant, have organic taste, and are resistant to pests and diseases. We are also not in any way under pressure to buy new seeds whenever a new farming season starts,” he says. He added “People are embracing our local seeds because they are healthy, and doesn’t require one to use pesticides to spray against pest and diseases. instead here we use ashes to kill pests which have no effect on human health,”

Vicky Lukwiya, an agro-ecologist and the founder of the Ongako Community Seed Bank says the local seed varieties they are keeping were sourced locally while others were obtained from South Africa, Kenya, and Zimbabwe. She says within the Acholi Sub-region; they are currently coordinating with more than 300 small-scale farmers to breed local seed varieties.

Not all improved seeds can’t grow

Joe Erem Oyie, the Development Communication Officer National Agricultural Research Organisation (NARO) Ngetta Zardi however says NARO has developed several crop varieties that can be replanted after first planting. According to him, NARO has so far released OPV (open-pollinated varieties) including maize varieties that can be replanted like Longe 5D and MM3 which perform quite well.

He notes that the seed improvement is meant to cope with the increasing demand for food due to rapid population growth. While the most common hybrid seeds in the country are maize, sunflower, and tomatoes, Dr Walter Anyanga, a cereals scientist at the National Semi-Arid Agricultural Research Institute in Serere says there is a possibility of introducing sorghum hybrid varieties in the near future.

Over the years, the Ugandan government has scaled up its research capacity in developing and improving seeds through state agencies and private sectors. A total of 33 seed companies including local, regional, and multinational like Corteva Agriscience, Limagrain, Syngenta, Monsanto/Bayer, and Advanta are involved in the production of crop seeds in the country currently.

Just recently, the government revealed that NARO had introduced two new maize varieties; Naromaize 63 PVA an orange maize breed rich in Vitamin A, and Naromaize 64STR. Agriculture Minister Frank Tumwebaze told Parliament in a plenary while presenting a statement on World Food Day on October 25 that the cabinet had approved a proposal to establish a Food and Agricultural Authority that will be mandated with food-related matters.

Paul Kilama the Production officer in charge of Gulu District however admits that hybrid seeds do not contain the same food nutrition as the local seeds whose nutrient contents haven’t been altered. He underscored that hybrid seeds argue that while they produce higher yields for farmers, traditional seeds play an important role in the seed system and biodiversity.

“Because traditional seeds are self-thriving, they become the basis of seeds, if you keep going for seeds and fertilizer to the input seeds, your security is determined by someone else. Traditional crops are important in the seed system and integration of biodiversity,” he said. Uganda has approximately 68 percent of its population employed in the agricultural sector according to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBOS) 2022 report.

However, the Integrated Seed Sector Development Uganda report indicates an estimated less than 15% of the farmers use quality, mainly hybrid seed. In a bid to guarantee the safe development and use of biotechnology, the parliament in November last year passed the Genetic Engineering Regulatory Bill 2018. Formerly known as the National Biotechnology and Biosafety Bill of 2012, it aims to provide a regulatory framework that facilitates the safe development and application of biotechnology.

Earlier in 2017, the President declined to assent to the bill and recommended for establishment of several gene banks and seed banks across the country to preserve biodiversity.

****

This story was produced with the support from the Agroecology School for Journalists and Communicators and the Eastern and Southern Africa Small Scale Farmers’ Forum (ESSAF) Uganda.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price