Paris, France | AFP | When Rwandan genocide suspect Felicien Kabuga was arrested at his home on the outskirts of Paris in mid-May, it marked an abrupt end to a quarter of a century on the run.

Without the coronavirus pandemic, which forced his children out of the shadows to help the octogenarian, the man with a five-million-dollar bounty on his head might never have been found.

At dawn on May 16, French police entered a modern five-storey apartment block in the eastern Paris suburb of Asnieres-sur-Seine.

On the third floor, they broke down the door and burst in to find one of the suspect’s sons, Donatien Nshimyumuremyi.

Next to him was an elderly man with a scar on his neck -– an identifiable feature of Felicien Kabuga.

A DNA test confirmed they had detained the man accused of financing the 1994 genocide during which 800,000 people were slaughtered over 100 days.

The businessman had been living in France under a false name for at least four years, said a source close to the case who asked not to be named.

Kabuga, who officials say is 84 but proclaims to be 87, was taken to hospital several times between 2016 and 2019.

He was treated under the name Antoine Tounga, assisted by his daughter who served as his interpreter.

– Children’s help –

Kabuga’s children helped him repeatedly during his time on the run, but it is through them that French, Belgian and British police eventually tracked him down.

European police forces lost his trace in 2007, when they failed to arrest him in Germany where he was treated for a throat tumour.

When Kabuga’s wife Josephine Mukazitoni died ten years later in Belgium, investigators closely watched the funeral.

But he didn’t show up.

“Several times we had leads about his presence in France. We tried to arrest him in Paris on Christmas Eve a couple of years ago, but without any success,” a police source who used to work on the case told AFP.

But in March 2020, the French police received another lead.

According to their British colleagues, Kabuga’s daughter, who lives in London, was in touch with him and regularly visited a Parisian suburb.

Using the daughter’s GPS location, the police tracked her movements between the UK and France at the height of the coronavirus pandemic when much of Europe was in lockdown.

Several weeks later, the suspect’s flat was identified through the matching of the daughter’s GPS data with that of her brothers and sisters who also regularly visited.

“His dependency and the lockdown forced his children to reveal themselves,” said a person with knowledge of the case, who requested anonymity.

– Protection money –

Kabuga’s children weren’t his only helpers. Once one of Rwanda’s richest men, his fortune appears to have helped him buy his protection.

The organization Rwandan Community of France (CRF) has asked prosecutors to open an investigation to identify those who assisted him whilst he was on the run.

His flight from justice began in July 1994, when he reached Switzerland. Deported to the Democratic Republic of Congo, known then as Zaire, he moved on to Kenya.

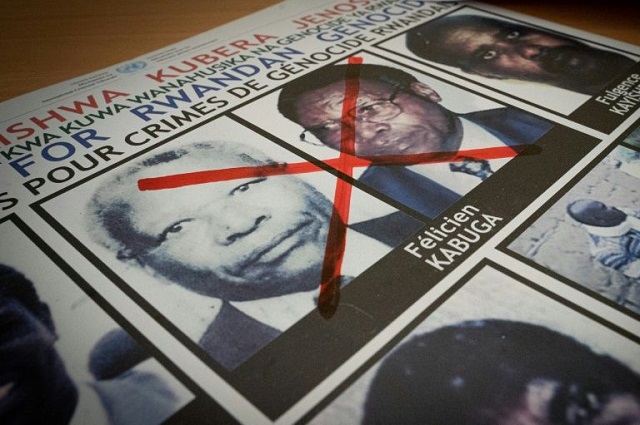

Kabuga was indicted in 1997 by the UN International Criminal Tribunal for Rwanda on seven counts, including genocide.

Between 1997 and 2006, he avoided at least three arrest attempts.

In 2002, the American government published a photograph of Kabuga in the Kenyan press, offering a five-million-dollar reward for any information leading to his arrest.

After Kabuga’s treatment in a German hospital in 2007, the US believed he had returned to Kenya.

Relations between the two countries turned sour as the US accused Kenya of refusing to cooperate.

But it now appears possible that Kabuga never returned to Africa after his operation in Germany.

Kabuga is expected to stand trial at the Mechanism for International Criminal Tribunals (MICT) in Tanzania, after a French appeals court gave its green light for his extradition on Wednesday.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price