Experts demand more money for Non-communicable Diseases

Kampala, Uganda | FLAVIA NASSAKA | Demands by some experts for more investment in medicines, facilities, and training of medical staff to handle rising cases of diseases like cancer, diabetes, and heart diseases that are technically referred to as Non-Communicable Disease (NCDs) has become a bid debate in Uganda’s health sector. Opposing the demand for more investments are experts who say interventions against NCDs are, in fact, already over funded.

The debate is happening as the World Health Organisation projects that NCDs are rapidly rising and replacing HIV and malaria as the leading causes of death – and are projected to exceed communicable maternal, perinatal and nutritional diseases as the commonest causes of death by 2030.

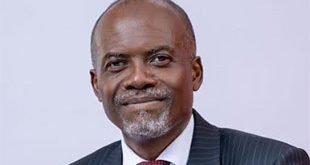

Dr. Gerald Mutungi, the Programme Manager for Non-Communicable Diseases at the Ministry of Health, is among those seeking more funding. He says he cannot put a figure to what is currently invested to cater for NCDs but he says it is one of the least funded areas and that he is looking for more money for the programme.

“The ministry is now looking for partners. Donors don’t have as much interest in this area even if diseases like cancer are becoming a crisis,” he told The Independent in an interview.

Under the search for new partners, 06, the Ministry of Health on July 06 signed a Memorandum of Understanding with Novartis; the international pharmaceutical company from Switzerland, to provide cheaper drugs for NCDs.

Under the agreement, treatments will be provided at US$1 per treatment per month supplied through the National Medical Stores and Joint Medical Stores. With the MOU, it means with the same amount of money that government usually spends on buying the drugs, more doses will be bought and therefore more patients will be able to get drugs at the health facilities. Mutungi says since there is a shift from low to high quality medicines, some brands are set to be dropped. This deal is expected to increase patients’ access to treatment for NCDs.

According to Mutungi , the first order which is expected early October will include Valsartan that treats hypertension, Amlodipine for hypertension and heart failure, Vildagliptin for diabetes, Amoxicillin dispersible tablets for respiratory infections, Salbutamol for asthma and Letrozole for breast cancer.

The medicines in the portfolio have been selected based on their medical relevance – either because they belong to a class included in the World Health Organisation model list of essential medicines or belong to the most frequently prescribed medicines in these disease areas.

Mutungi, however, says patients might still fail to get treatment because very few people seek care for NCDs despite every four adults suffering from an NCD-related disease. Mutungi blames the increase in NCDs on poor lifestyle choices among the population.

He quotes the 2014 NCD risk factor survey which reveals that 10% of Ugandans aged 18-69 years have at least three risk factors for NCDs with 20% aged 45-69 years having more than three risk factors which include obesity, tobacco use, and poor nutrition and that screening for cancer of the cervix, which is the leading cause of cancer death in Uganda, was only 10% among women aged 30-49 years.

Moses Mulumba, the Executive Director, Center for Health Human Rights and Development (CEHURD) says reducing NCDs would require the same efforts like those that have been put in managing HIV/AIDS. He says policy makers need to wake up and change the mode of healthcare delivery such that more funds are put into awareness, control and prevention of these emerging diseases. He says the government needs to revise the health budget from most of its health expenditure going into human resource to actual investment in the sector and not projects.

“Uganda is not prepared at all for the increasing burden of heart disease and cancer. Even in HIV, I wouldn’t say it’s been over funded because we live in uncertainty that if donors stopped giving us money today we can easily fall back in the 1980s situation. The problem with NCDs is we don’t even have the favour of donors,”Mulumba says.

Another health rights advocate Dennis Odwe, the Director, Action Group for Health Human Rights and HIV/AIDS (AGHA) says failure to fund NCDs, yet they have become one of the biggest killers, is a result of lack of advocacy and publicity.

“One would argue that donors are not putting money into averting these diseases but how will they consider it when there’s nothing to show demand,” he says. He says, for instance, there is no real data to show how big the problem is which poses challenges on advocacy. He says in case of cancers, which are one of the most devastating NCDs, there is almost only one activity – cervical cancer vaccination for girls that the Ministry of Health is engaged in. He says this compares badly against the many activities for HIV/AIDs which are done by not only the ministry but different government bodies like the Uganda AIDs Commission and the parliamentary committee on HIV.

For NCDs it’s only in April this year that the parliamentary forum on NCDs was held to promote early screening and prevention. But, even these small efforts are at the center as people in the countryside continue dying without even getting to know what is killing them.

“Regional hospitals don’t have functional clinics to handle cancer cases and by the time one is referred to the national referral, it’s irreversible,” Odwe says, “When it comes to training, there are also still loopholes for instance the country has just a few oncologists with the majority being based at the center.”

Odwe says NCDs have the capacity of overwhelming the health system and potentially reversing the health gains if policy makers do not plan adequate interventions.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price