Bouaké, Ivory Coast | AFP | Every time Catherine Coulibaly’s 19-year-old son had to make a routine appointment with the cardiologist for his heart condition, she gritted her teeth as she silently counted the financial cost.

It wasn’t just the hospital fee — there was the transport, food and accommodation, too, all of it amounting to a hefty burden for an Ivorian family on a modest income.

But thanks to telemedicine — consultations that doctors conduct through the internet or by phone — this cost is now a fading memory.

Her son can book an appointment at a telemedicine facility in a nearby town in northern Ivory Coast.

There, he is attached to monitoring machines which send the data sent to Bouake University Hospital in the centre of the country, where it is scrutinised by a heart doctor.

The fledgling technology has long been championed by health advocates for poor rural economies.

Ivory Coast has become an African testbed for it, thanks to a project linking the Bouake hospital’s cardiac department with health centres in several northern towns, some of which are a four-hour drive away.

Telemedicine “caused a sigh of relief for the population of Bouake, Boundiali, Korhogo, everyone,” says Auguste Dosso, president of the “Little Heart” association, which helps families with cardiac health issues.

Some 45 percent of the Ivorian population live below the poverty line, according to the World Bank’s latest estimate in 2017. And the minimum monthly wage — not always respected — is only around $100, or 90 euros.

– Heart disease surging –

The pioneer behind the scheme is cardiologist Florent Diby, who set up an association called Wake Up Africa.

In Ivory Coast, heart disease, diabetes and other “lifestyle” ailments are surging, Diby explained.

“Urbanisation is making people more sedentary, and there’s the rise in tobacco consumption, changes in diet, stress,” Diby said.

Three decades ago, only around one in eight of the Ivorian population had high blood pressure — now the figure is one in four, on a par with parts of Western Europe.

But in Ivory Coast — and across Africa — well-equipped cardiology units are rare.

“Ninety percent of heart attacks can be diagnosed by telemedicine, so for us cardiologists it’s a revolutionary technology,” said Diby.

The beauty of the telemedicine scheme is that neither the doctor nor the patient has to travel far.

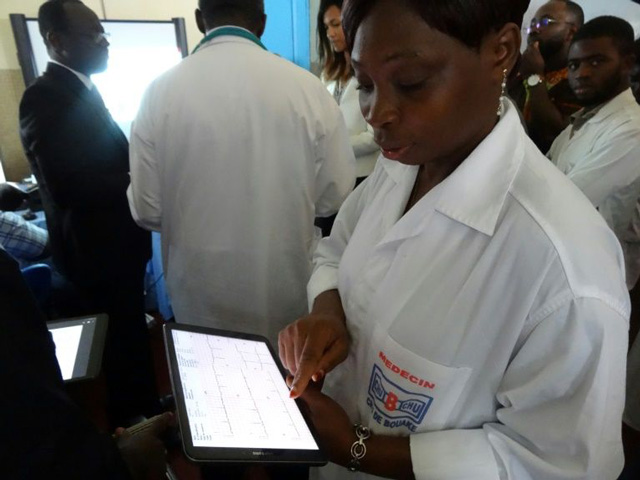

The cardiac patient is hooked up to the electrocardiogram (ECG) and other diagnostic machines with the help of a technician in a local health centre, which is connected to a computer in Bouake’s University Hospital.

The cardiologist there can then see the results in real time, provide a diagnosis and prescribe treatment.

The five-year-old project has already linked 10 health centres to the seven cardiologists at Bouake, enabling 4,800 patients in other towns to receive consultations by telemedicine each year. The goal is to expand this to 20 sites, doubling the intake.

Expertise France, the French public agency for international technical assistance, subsidises up to 185,000 euros of the network, which pays for equipment such as computers, artificial intelligence software and internet connections.

Diby is now calling for telemedicine to be expanded in other medical fields such as neurology and psychiatry, not just in the Ivory Coast, but across West Africa too.

That opinion is shared by other experts. Sixty percent of Africans live in rural areas, where shortages of doctors are usually acute.

But numerous hurdles need to be overcome, especially investment in computers and access to the internet, according to a 2013 analysis published by the US National Library of Medicine.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price