Entebbe conference of experts announces way forward

Kampala, Uganda | RONALD MUSOKE | Ramping up its vaccine and pharmaceutical manufacturing is probably one of the most audacious goals set by the African Union recently and players in the sector say manufacturing can move from the current 1% of local production to about 60% by 2040

In fact, the African Union has a new public health order which also seeks to increase the manufacturing of therapeutics and diagnostics as one of the continent’s pillars to ensure health security for its 1.4 billion people.

“Our ambition is to progressively increase the share of vaccines manufactured within the continent from 1% to 60% by 2040,” Yared Yiegezu Zegiorgis, a Senior Research Data Analyst at the Addis Ababa-based Africa Centres for Disease Control and Prevention (Africa CDC) recently told delegates who met in Uganda to discuss the state of vaccine and pharmaceutical production in Africa.

The AU has already set up and mandated the Partnerships for African Vaccine Manufacturing (PAVM) to develop a framework for action to execute this plan.

According to Zegiorgis, the PAVM framework, which was launched in 2021, is on a multi-stage journey to realize the AU’s new public health order with the current focus being “strategy implementation.”

This includes operationalisation of the secretariat established in 2022. The AU has also launched the implementation of the prioritized activities that benefit broader ecosystems beyond vaccines.

Zegiorgis said the AU is prioritizing vaccine manufacturing for up to 22 diseases including; Diphtheria, Whooping Cough, Tetanus, Hepatitis B, Yellow Fever, Tuberculosis, Measles, Typhoid Fever, Cholera and Meningococcal (legacy diseases).

And in the near future, the AU intends to expand production of HPV, HIV, Malaria, Pneumococcal, COVID-19 and Rotavirus vaccines and therapeutics while it is also keeping an eye on Ebola, Chikungunya, Rift Valley Fever, Influenza, Lassa Fever and “Disease X” the name the World Health Organization recently coined to refer to any little-known disease.

“These will require a breadth of technology platforms (live attenuated, inactivated virus, subunit, virus-like, particles, viral vector and RNA/DNA), along the different steps of the value chain,” Zegiorgis said.

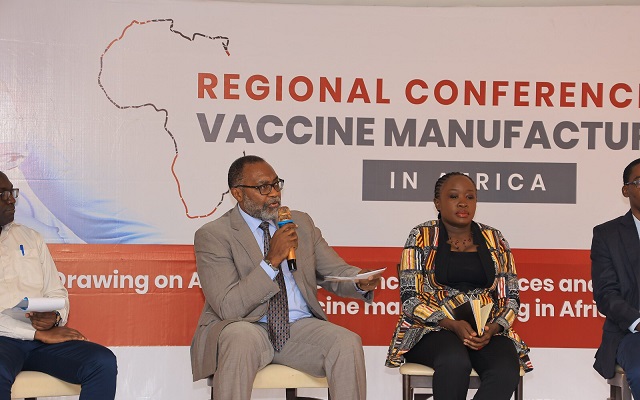

The Entebbe Conference

The regional conference which ran from June 12-14 in the lakeside town of Entebbe attracted players from eastern and southern Africa. It also included; the African Union, academia, civil society, policy makers from relevant government ministries, departments and agencies (MDAs) in Uganda, pharmaceutical manufacturers associations and development partners among others.

The conference was convened by Afya Na Haki, a Kampala-based health policy think tank to discuss the state of vaccine manufacturing in Africa and the continent’s preparedness for future pandemics.

The think tank is working with partners in eight African countries under a programme called, “Advancing Regional Vaccine Manufacturing and Access in Africa (ARMA).” The partners are from Uganda, Nigeria, Rwanda, Tanzania, South Africa, Kenya, Senegal and Zimbabwe.

The programme launched in Kampala this March seeks to understand the role of civil society and other players in advancing vaccine manufacturing in Africa and benchmark experiences and best practices from research and regional advocacy initiatives to inform advocacy and policy.

“We are bringing together unified voices and experiences so that we contribute to the ongoing conversation to ensure that Africa builds capacity to ensure that we have adequate vaccines for our population,” Abdul-Karim Muhumuza, the head of partnerships and communications at Afya Na Haki told The Independent during the launch of the programme in March this year.

“We shall ensure that different partners in the region speak to the issues and the challenges affecting vaccine research and development and manufacturing to ensure that we engage our governments, regulatory bodies, civil society communities to have a unified voice that enables us to have health security for Africans.”

Africa vaccine/pharmaceutical handicap

While launching the programme in March, Dr. Moses Mulumba (PhD), the Director General of Afya Na Haki told The Independent that what happened to Africa during the recent COVID-19 pandemic prompted the civil society initiative. He said the pandemic demonstrated the underdeveloped capacity of member states to Africa-focused research, development and manufacturing of vaccines.

“The civil society partners are concerned that the rest of the world rarely cares about diseases that are here in Africa but have not impacted them,” he said, “On the African continent, the word ‘global’ does not apply. We have seen it with challenges of Monkey Pox and Ebola.”

Mulumba said African oversight bodies have also been found to be lacking the necessary resources to institutionalize vaccine development and are heavily reliant on countries and organisations in the West.

“There has been that realization that unless we ramp up pharmaceutical manufacturing on the continent, we are not going to be able to cope with the disease burden,” he said.

He said the programme seeks to understand the landscape of pharmaceutical manufacturing and ensure that powerful commitments and resolutions made by the African Union and individual African countries are actually implemented.

At the Entebbe conference, Nimrod Muhumuza, the head of research at Afya Na Haki told the delegates that Africa is expected to see a three-fold increase in vaccine demand by 2040. Yet, the continent with a population of 1.4 billion people today and expected to get to about 2 billion by 2040 produces only 1% of the vaccines it administers.

There are 375 drug manufacturers on the continent and vaccine production on the continent remains low and is largely concentrated in five countries (South Africa, Morocco, Tunisia, Egypt and Senegal), he said.

Muhumuza also noted that pharmaceutical manufacturers in sub-Saharan Africa are largely clustered in just nine of the 46 countries including Uganda, and they are mostly small, without operations that meet international standards.

By comparison, China and India, each with roughly 1.4 billion people have as many as 5,000 and 10,500 drug manufacturers respectively. And the sub-Saharan Africa market’s value is still relatively small, at roughly US$ 14 billion compared with roughly US$ 120 billion overall in China and US$ 19 billion in India.

In sub-Saharan Africa, only Kenya, Nigeria and South Africa have a relatively sizable industry, with dozens of companies that produce for their local markets and in some cases, for export to neighbouring countries.

Almost all of them are drug-product manufacturers they purchase active pharmaceutical ingredients (APIs) from other manufacturers and formulate them into finished pills, syrups, creams, capsules and other finished drugs.

Up to 100 manufacturers in sub-Saharan Africa are limited to packaging: purchasing pills and other finished drugs in bulk and repackaging them into consumer-facing packs. Only three, two in South Africa and one in Ghana are producing APIs, and none have significant research and development activity.

Yiegezu Zegiorgis from the Africa CDC corroborated Muhumuza’s findings. He said eight African countries contribute 80% of local production while just 20% of the manufacturers produce APIs. And just 2% of investments in research and development of vaccines and pharmaceuticals is made in Africa.

The continent also has low integration along the pharmaceutical value chain with just 30-40% of therapeutics manufactured locally and 40% of financing and procurement is by the private sector and 25% of manufacturing is done by multinationals.

Zegiorgis told the delegates that localizing vaccine and pharmaceuticals research, development, manufacturing and innovation would improve the health security and capacity for emergency response on the continent. He said it would improve public health, improve access and affordability, and accelerate ongoing regional harmonization initiatives to facilitate trade and elevate technological expertise and capabilities and facilitate economic growth across the continent.

He said the initiative would also provide an opportunity on the African continent to tap into a market that was in 2020 estimated at US$30 billion and has been growing at about 4% (US$4 billion) per annum in the past five years. The African Union Commission expects this market to expand to about US$7 billion per year over the next five years.

Continental challenges

Rangarirai Machemedze, the executive director of the Zimbabwe chapter of the Southern and Eastern Africa Trade Information and Negotiations Institute (SEATINI) told delegates that pharmaceutical production in Africa; particularly in east and southern Africa, is affected by many challenges.

He mentioned deficits and incapabilities in research and development, intellectual property rights, already established markets, regulation shortfalls, inadequate human and technical skills, poor capital markets for finance and competition laws and policies.

He was presenting a paper titled, “Advancing Local Pharmaceutical Production through Legislation and Institutions Reforms in the East and Southern Africa region.”

He said policies and laws are rarely implemented, costs are high because of very old plants, skilled workers cannot be retained, utility tariffs (water and electricity) are high, and working capital and technology are lacking.

However, Dr. Moses Mulumba told delegates that although in the short term, it may appear expensive to set-up pharmaceutical plants on the continent, in the long run, it will prove to be more cost effective.

“Africa has woken up to the realities; we have launched the pharmaceutical manufacturing plan for Africa; we have the African Medicines Agency (AMA). There is also the African model law which is critical and the AfCFTA is also an initiative which will give Africa opportunity where we want to reach,” he said.

Kylian Songwe, the Regional Director of the Global Healthcare Public Foundation agreed.

“We saw that during the COVID-19 pandemic; whether the Western nations hoarded COVID-19 vaccines or not, that is irrelevant; they were simply taking care of their people and their national security,” he told The Independent.

“When you want to become a sovereign nation, you must be able to take care of your people because it becomes a national security issue when you cannot take care of your people.

“Instead of us complaining that they were hoarding vaccines, we need to answer the question of how do we take care of our national security which is our human resources. So, the timing is right, the initiative is good,” he said.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price