Abidjan, Ivory Coast | AFP | Vieux-Pere runs his fingers through his patchy hair as he remembers escaping being lynched.

“The locals caught me and hit me everywhere, I still have scars on my skull,” he says.

“That’s why I can’t get my hair right,” he says with a laugh.

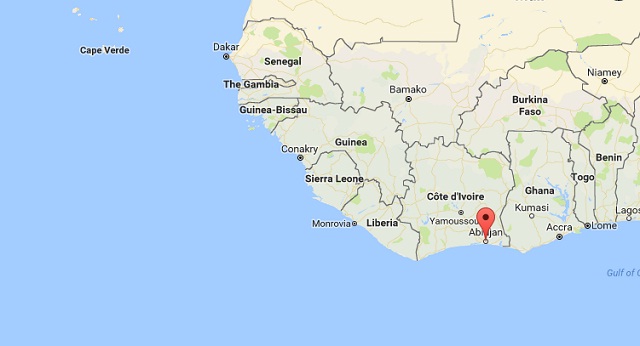

For nearly 10 years the 24-year-old was in a “microbe” gang, the name residents have given to the youth gangs who rob, attack and sometimes kill to get by in Ivory Coast’s economic capital Abidjan.

Hundreds of youngsters — some as young as 10 — are in the gangs, according to the charity Indigo, which has helped about 40 former members reintegrate into society.

Hated as much as they are feared, the gangs sprang up in poor areas of Abidjan’s densely populated Abobo suburb during the decade of civil unrest in Ivory Coast between 2002 and 2011 that split the country in two.

The rising violence led to the appearance of child soldiers, who became the first “microbes”, or “germs”.

Public anger against their marauding has sometimes boiled over. After mobs of residents lynched a number of gang members, a microbe leader was tortured, beheaded and burnt in 2015.

Vieux-Pere, who only goes by his nickname, says he was never afraid because he liked to fight. He left school at the age of seven.

“I saw people fighting and I liked it a lot, I wanted to join them,” he says, sitting in the shadow of a youth centre in Abobo.

“I found myself with the strongest guys in Abobo and I was proud. I liked their way of life. Peace to their souls — they are all dead,” he said, quoting some of their gang nicknames: Dragon, Gongo…

Vieux-Pere left his family home after fighting with his father over his gang membership. He slept on the streets for two years before finding a small house “with a mattress” in Abobo for 15,000 CFA francs a month ($27, 22 euros).

– The ‘Air France’ gang –

He joined the microbe gang “Air France” in 2008 and spent most of the next decade robbing people on the streets, often at knifepoint or threatening his victims with his fists.

“Very quickly, I had to fight the boss, Ismael, to win my place and show I was not afraid,” he says, pointing to a large scar on his elbow from one of the gang leader’s machete blows.

There were about 40 adolescents in the gang, which operated mostly at night.

“We met in the evening with the group and left with our machetes in our backpacks,” he says.

“Sometimes we rented gbakas (private minibuses) to take the whole gang. We attacked everyone.”

But Vieux-Pere says he never killed anyone.

“Those of us who killed are now dead.”

He was nearly killed himself when a gang raid on one of Abidjan’s biggest markets went wrong.

His medical care was paid for by “his guys” with the spoils from the raid, in accordance with the gang’s rules.

“As soon as we stole the money we kept half of it for the gang in case of a hard blow, to pay bail — or for partying,” he said.

– A new life –

Vieux-Pere became leader of Air France in 2015 after his predecessor died in prison.

“Ismael entrusted me with the jail before he went to prison. They saw that I was man enough,” he says.

But the new gang leader dreamed of a better life. On his birthday on March 12, 2016, he quit Air France with two friends.

“I didn’t feel happy anymore. I was making money but I always asked the question: ‘What if I attacked my parents like I attacked the others?'”

Thanks to a microbe reintegration programme by Indigo, the young man now hopes to set up a car parts business.

“We all want to start a new life,” he said of the charity’s 40 reformed microbe gang members.

Illiterate, he has been going to night classes for reading and writing for a month. He has found a little work scrap metal dealing and working at a junkyard, and is even back in touch with his family.

But he still lives in the small house with another former member of Air France.

“The gang is dead,” he said. “Some left after I did. I don’t know what became of the others.”

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price