The right of journalists to safety at work is often pursued as a collective cause but the pain inflicted is personal

COMMENT | JOSEPH WERE | I have been a journalist for about 30 years. I fully understand that being a journalist means you can be harassed, sued, beaten, tortured, jailed, and killed.

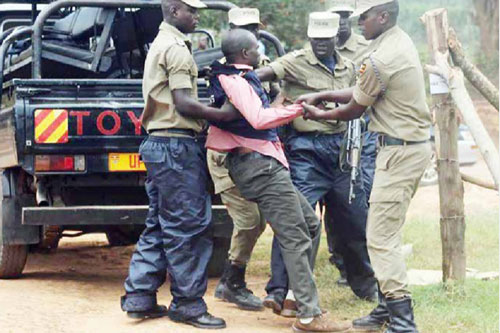

Still, I found video images of journalists being clobbered by security forces as they attempted to cover a news event at the United Nations Human Rights office in Kampala on Feb.17 disturbing.

Many journalists were left bleeding, with head injuries, sprained and fractured limbs, and bruised backsides. Many people expressed shock and condemnation. In reality, Ugandan security personnel attacking journalists is common. Sometimes the attacks come from members of the public.That is why the flowing blood and broken bones are not what I found most disturbing.

What I found shocking is that many journalists are unprepared for the attacks. Watching them scamper with the soldiers in hot pursuit, I wondered if any of them had been prepared for the onslaught. Many of the male journalists wore tight pants and jackets and the women wore tight-fitting dresses. Almost all did not have a helmet. A few had press jackets. Some carried heavy TV equipment. Surely jeans, T-shirts, and hard shoes would have helped. We used to wear them before the era of celebrity journalists.

As a trainer of journalists who report in dangerous conflict situations, I wondered if any of them had any training in how to cover violent protests and conflicts. That should be mandatory for all Ugandan journalists in the face of endless political unrest.

As media scholars Meghan Sobel Cohen and Karen McIntyre point out in their 2020 research report titled ‘The State of Press Freedom in Uganda,’ the Ugandan government and press have “settled into a predictable relationship” where the government sporadically “lashes out” at the media in various ways, but “such heavy-handed actions tend not to permanently disrupt operations.”

That is a quote that every practices journalist in Uganda needs to familiarize with. It is from a 2017 report by Freedom House; the American NGO. It means individual journalists may be beaten but that will not stop the journalism collective from trudging on. The show must go on.

Many journalists know that expression. It originated in the circus business where performers routinely get injured. It means that although the defenders of the right of journalists to safety at work often pursue it as a collective cause, the pain inflicted is personal.

Aware that they could suffer attacks during the recent 2020 election in the country, the Ghana Journalists Association set up a GH¢20-million insurance package (Approx. UShs 13 billion) for 500 of its members accredited to cover the elections. It covered injury, disability, or death in the line of duty.

Still, every smart individual journalist knew they were responsible for their own safety. Only you feel the pain when your head is smashed, you are jailed, or receive threatening phone messages. Therefore, protect yourself.

It pains me to see young, inexperienced journalists venturing unprepared and unconcerned into violent protest and conflict situations. I am reminded about how, in October 1996, I ventured into the jaws of Joseph Kony’s Lord’s Resistance Army rebels.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price