The creation of the KCCA was meant to change all that. In the official story, the authority was designed to transform the city, under committed, experienced leadership — a narrative that easily meshed with the institutional reform agenda pushed by agencies like the World Bank. The more cynical view sees it as a power-grab by Uganda’s authoritarian president, Yoweri Museveni, trampling on local democracy to stamp his will on the capital.

Whatever the truth of the politics, the finances didn’t lie. When the KCCA took over, the city operated 151 bank accounts. Suppliers were rarely paid on time. Revenue collection was farmed out to grafting middlemen, with many taxes never making it to the public purse. “Nothing was working,” says Patrick Musoke, the KCCA’s director of strategy, “and most of the good contractors had given way because of the massive corruption.”

Many of the KCCA’s new officials came from the national tax authority. They soon set about the unglamorous work of rejigging the city’s systems. The spider’s web of accounts was consolidated into eight, overseen by the central bank. Staff were given more computers — it had been one for every five officials — and databases were digitized. An automated system, dubbed “eCitie,” allowed citizens to pay taxes through their phones. Streamlining tax registration, in partnership with national authorities, brought 110,000 informal businesses into the tax net.

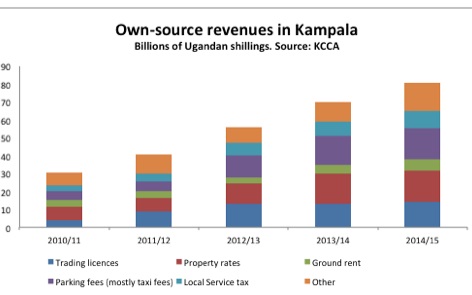

Kampala still doesn’t pay for itself. That is hardly unusual: Local taxes and charges often amount to less than a 10th of African cities’ revenues, says Mihaly Kopanyi, a consultant, with central government and development agencies making up the shortfall.

But thanks to the reforms Kampala now generates a third of its own income. There is plenty that can be taxed locally; after all, the city accounts for 60 percent of Uganda’s GDP. “If everything goes to plan,” says Sam Sserunkuuma, KCCA director of revenue collection, “then the city will be self-sustaining in the next seven to 10 years.” That sounds optimistic, but is suggestive of the KCCA’s ambition.

The KCCA has brought more visible changes too. “It has organized the streets, and we have cleanliness,” says Aaron Aojaar, a banker, waiting for a new commuter train service, which has been running since December. People should get behind the new authority, he says: “It takes time to transform a third world town.”

That is a common sentiment among the middle-classes. But in the clamor of downtown Kampala, where reform has been most intensely felt, Aaron’s optimism is not widely shared.

UNEQUAL BURDENS

Kampala is a divided city: It was meant to be that way. Fearing malaria, British administrators decreed the segregation of the town into European, African and Asiatic zones. That was hard to enforce, but custom and land prices did the job anyway. A revolted town planner, writing in 1931, described Kampala as “a strange mixture of the delightful and the hideous”: The “splendid hillsides” of the rich and the “death-dealing swamp” of the valleys, where the poor clustered in makeshift shacks.

Colonialism is gone. The protective “green belt” around the European settlement is now a golf course. But social class is still mapped upon the steep contours of the city. On Nakasero hill, crisply dressed professionals stroll between banks, embassies and government buildings. Yet stumble down the sloping streets and you drop into another city entirely. Motorbikes curdle the traffic flow. Hawkers flog secondhand clothes. Shopkeepers trade their wares in labyrinthine plazas, constructed like honeycomb above congested streets.

At the center of it all, in the hollow of the hillside, is the Old Taxi Park: a “seething, kidney-shaped bowl,” as Ugandan novelist Moses Isegawa puts it in his Abyssinian Chronicles. Four-fifths of motor journeys in Kampala use minibus taxis, and many of those journeys end here. Viewed from above, the taxi park is a mosaic of glinting roofs — a natural amphitheatre where the first scenes of reform were played out.

The park used to be managed by the Uganda Taxi Operators and Drivers Association, a thuggish clique masquerading as an industry body. It had a contract to remit Sh392 million ($120,000 U.S.) to the council each month, but extorted several times that amount from helpless drivers.

One of the first acts of the new KCCA was to cancel the contract, bringing tax collection back in-house. Revenue from taxis doubled in a year. So-called “road user fees” (which also include car parking) are now the second-largest source of revenue, accounting for a fifth of last year’s total.

Drivers had no affection for the old regime, but found little to love in the new one. Though fees did not rise, the new monthly rate did not take account of days when vehicles were off the road for repairs. Drivers also complained about the KCCA’s methods: impounding taxis and, some allege, turning a blind eye to the heavy-handedness of its enforcers.

The KCCA was soon dragged into the fraught politics of the taxi parks. Rival taxi associations jostled for influence, at times violently. Some drivers refused to pay the monthly fee, organizing sit-down strikes and challenging the levy in court. When a radical faction held elections in 2014 the KCCA refused to recognize the result, backing an alternative, more compliant grouping. “We agreed to pay the fee because there is no escape route, but it is too high” says Mustafa Mayambala, winner of that unofficial vote.

It is not just the taxi drivers who feel they are shouldering the fiscal burden. Kampala’s second fastest-growing source of revenue is trading licenses. The rates are set by central government, and vary with business type and location: A city center shop, for example, pays Sh210,000 ($65 U.S.) a year. Charity Nanono, who runs a stall selling children’s shoes, thinks that small vendors like her are unfairly put upon. “After you pay rent, electricity, food and transport, what you get in profit is very little.” Others wonder where the money goes, and why they still have to pay extra charges for garbage collection and public toilets.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Very interesting article.

Wow, beautifully crafted article