KCCA, WFP concerned as number of children without food grows from 13.5% to 18%

Kampala, Uganda | AGNES E NANTABA | More people are going hungry in Kampala district; home of the nation’s capital. This is odd because Kampala is the center of the richest people in Uganda. But as many starve, Kampala also has many well-off people whose children are getting fatter or obese due to over-eating. So what could be going wrong?

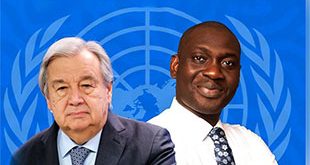

These are some the questions Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) and the UN agency, World Food Programme (WFP), want answered. They have jointly hired the Makerere University School of Public Health, to investigate the nature and magnitude of both lack of food and bad feeding among the poor and better-off households in Kampala. Results of the joint comprehensive study will guide KCCA and WFP in planning and assisting people in need.

When, on Oct.18, the Kampala Capital City Authority (KCCA) Executive Director, Jennifer Musisi, and WFP’s Country Director, El Khidir Daloum, at City Hall signed the Memorandum of understanding to do the research, they revealed that they suspect a link between poverty, the rapid expansion of the city, and the lack of food and bad feeding; especially among children.

“We are looking for scientific evidence that can guide our assistance to vulnerable households and our overall city strategic plan,” Musisi said.

Daloum said the new partnership will assist Uganda in working to achieve key Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs); especially SDG2 that aims at achieving zero hunger. This is important, according to Daloum, because Kampala city generates 60% of Uganda’s wealth.

Kampala also ranks among the top 10 fastest growing cities in Africa, according to Musisi. And the city is expanding at a rate of 5 percent per year, currently with a day-time population of five million people. She says most of the newcomers flocking the city are people from the rural villages who end up in low income areas around Kampala and are leading to rapid growth of slums.

“Many people are arriving in the city to look for work and finding themselves squeezed into settlements where basic social services are limited, sanitation is poor,” Musisi said, “And, as result, their children are prone to infections and ill health. Moreover, these same households can hardly afford regular healthy diets.”

Children below five are the most hit and many of them, up to 18% of all children in the cohort, according to WFP, are stunted. That figure is far lower than the national figure of 29% stunting, according to WFP estimates. But there is concern because the acceptable incidence of stunting in Kampala is 15% and 10 year ago it was much lower at 13.5%.

According the WFP’s Daloum, the figures may vary in Kampala; with some areas being more affected by stunting than others.

Stunting danger

Stunting is a major concern because, if it occurs in early life before three years, it is an irreversible condition which has very bad effects on the sufferer. They are at greater risk of illness and early death, low level of learning, and growing into poverty. Some of these challenges can be inherited from stunted parents by their children.

According to the World Health Organization (WHO) child growth standard, a normal one-year old child should have a height of between 70cm to 80.5cm. At two years the baby should be between 81cm and 93.2cm. Any child who is shorter is considered either stunted or severely stunted if less than 77.9cm at two years. Any height above is considered tall. If this condition persists, and genetic factors are ruled out, the child may be deemed stunted. To estimate the level of stunting, experts take the average incidence in the population. Globally, up to 25% of children are stunted; especially in Africa and Asia.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price