Researchers call for harmonization of enforcement mechanisms used by Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania to tackle transnational crimes

ANALYSIS | RONALD MUSOKE | Lake Victoria, Africa’s largest and the world’s second-largest freshwater lake, shared by Uganda, Kenya, and Tanzania, has become a hotspot for environmental crime, according to a new report from the Pretoria-based Institute for Security Studies (ISS).

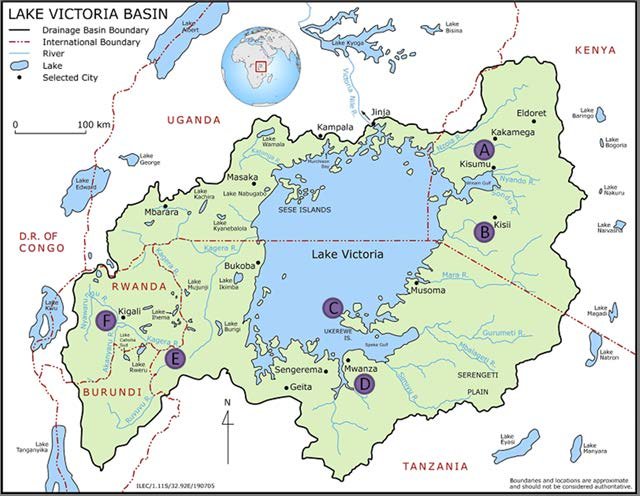

The 68,800 sq km lake that could easily pass for an inland sea, serves as a vital transport corridor, a source of fresh water, fish, and hydroelectric power, bolstering the economies of the three East African countries. Its basin also extends beyond these three East African countries, reaching as far as Rwanda and Burundi.

However, the report highlights Lake Victoria and its surrounding areas having become a hub for illicit markets, fueling transnational organized crime in the East African region. Documented crimes include; illegal, unreported, and unregulated (IUU) fishing, driven largely by the rising demand for Nile perch swim bladders (fish maw) in the Chinese market, as well as the illegal mining of sand, charcoal, and timber.

The report notes that Lake Victoria’s ecosystem, including its plant and fisheries resources, is under constant threat of extinction. Hardwood forests have been heavily exploited for boat construction, with one tree species, locally known as Mukebu (Cordia melenii), being particularly affected. This tree is listed on the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN) Red List as well as the National Red Lists in Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania.

The vast size of Lake Victoria makes it difficult to patrol, attracting illegal actors seeking to exploit the surrounding environment. The report notes that an estimated 40-50% of all fishing on the lake is illegal, unregulated, or unreported. Moreover, fish is not the only target; other natural resources in and around the lake have also experienced significant decline due to illegal activities.

According to the report, fishermen use the water mass not only to legally eke out a living but also to profit from overexploitation of the environment through practices such as illegal fishing and sand mining.

The study on transnational threats to Lake Victoria was launched in 2023 by the Institute for Security Studies through the ENACT (Enhancing Africa’s response to Transnational Organized Crime) project, in collaboration with the UN’s International Organization for Migration (IOM) and it was aimed at understanding better the threats and their impacts.

Clashing operational mandates

The study, conducted between July and November 2023, attributes the rise in illegal activities to the lack of a unified registration system for small boats, which has facilitated their use in such practices. It also highlights the clash in operational mandates among security forces from Kenya, Uganda, and Tanzania, which is undermining regional efforts to combat these and other crimes.

Dr. Willis Okumu, a senior researcher at ISS who focuses on transnational organized crime in East Africa and a lead researcher for the study, revealed during an online seminar on August 14, that illegal fishing constitutes the largest portion of criminal activity on Lake Victoria.

“Fisherfolk are the main actors because they are very knowledgeable about the lake; they are called consultants; owing to their navigational experience and geographical knowledge of the lake,” he said.

“At times, their boats are used to smuggle timber and charcoal as well as carry out illegal fishing. So, as they go about looking for a livelihood on the lake, they are basically committing a good percentage of crime within the lake.”

However, fisherfolk are not the only offenders on Lake Victoria. State officials are also implicated in environmental crimes for personal profit. Each of the three countries bordering the lake maintains a security presence: Kenya has the Kenya Coast Guard Services, Uganda operates the Fisheries Protection Unit (FPU), and Tanzania deploys the Tanzania Marine Police. These security forces are supported by the Beach Management Unit (BMUs) personnel, who are supposed to play a role in managing lake activities. However, that is not the case in and around the lake.

“The Beach Management Units are complicit in the commission of these crimes on the lake because they control the landing sites and beaches,” Okumu said, adding that in Uganda, BMUs often ask for bribes from Kenyan fishermen to fish in Ugandan waters.

He added: “The government officers who are supposed to ensure that the environmental regulations are followed often opt to take a bribe or look the other side when crimes are being committed.”

“The lake is vast and hardly policed and that has given rise to a lot of illegal operations that relate to environmental but also transnational organized crime,” he said.

Why organized crime is thriving on the lake

Maritime scholars argue that crimes in lakes, oceans and seas require the convergence of various elements: the presence of ready labour to carry out the crimes, the presence of a largely ungoverned water mass where illegalities can occur, and the allure of profit. At the local level, committing a crime in the lake requires the availability of the actor; their boat rowing or driving skills, and the intent/opportunity to profit from illegal fishing in the lake.

But proximity to Lake Victoria and the skills acquired to survive around the lake, such as fishing, swimming and boat rowing, can also be deployed in the commission of crimes for personal benefit. Yet, those who have the right skills (navigation) and tools (boat) to engage in activities such as illegal fishing often claim ignorance of the law when apprehended for trespassing in another country’s waters.

Illicit activities in Lake Victoria

Lake Victoria is home to different fish species including the Nile perch, tilapia, mudfish and silverfish (dagaa). Crimes on the water sometimes take place in specific areas due to the convergence of rich fish species at those locations or the presence of highly profitable endangered species on specific islands within the lake. This can attract illicit actors interested in benefitting from the exploitation of these natural resources.

Hotsports that attract high traffic due to the abundance of fish include Migingo Island at the water borders of Kenya and Uganda. Islands such as Remba (Kenya) and Goziba (Tanzania) attract high movement of people from East Africa and beyond due to the convergence of other illicit markets, such as the marijuana and charcoal trades, the trade in counterfeit goods, and the in-flow of undocumented workers, most of whom are youth and women who are forced into sex work, forced labour or working at entertainment venues.

The study notes that the lack of enforcement of fisheries regulations allows fisherfolk to not only legally sustain their livelihoods but also engage in various forms of illegal fishing. These violations include operating without the required gear or nets, fishing in prohibited zones, lacking necessary licenses or permits, and targeting juvenile fish, among other crimes.

To make the situation even worse, the enforcement officers in the three East African countries, the report notes, are also known to use violence and brutality in the lake to commit robberies of fish, fishing gear, fuel and boats, thus further promoting illegal fishing and environmental hazards.

For example, the deployment of the Fish Protection Unit in Ugandan waters of Lake Victoria since 2017 has led to various incidents, including extrajudicial killings, destruction of illegal fishing nets and gear, confiscation of fish, arrests and convictions, and the seizure of boat engines. Fishermen from Kenya and Tanzania have faced severe consequences, including drowning, theft of fish, and substantial fines.

Meanwhile, sand mining in Lake Victoria continues along the shores and inlets of the lake in Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania. At the local level, the key actors in sand mining are young men from these shores, local contractors and transporters who use it in the construction industry. But the Chinese investors have also sought authorization from state authorities to conduct dredging to expand ship routes, especially for oil tankers that ferry petroleum from Kenya to Uganda.

While dredging companies have been permitted, cases of Chinese companies being involved in sand mining through dredging emerged in 2018 when a Chinese firm known as Mango Tree Group was authorised to excavate sand at various sites in Uganda. The dredging was to allow for the docking of large ships and to enable water transport to other East African ports.

However, Ugandan data indicate substantial sand exports to China. A Daily Monitor analysis from 2014–2017 indicated a lack of regulation and oversight based on confusing export numbers.

Uganda, for instance, exported 14 tonnes of sand in 2014, earning US$4,800. In 2015, Uganda exported 22 tonnes of sand from the shores of Lake Victoria, earning US$68,000; in 2016, it exported 19 tonnes, generating US$1,074; and in 2017, it exported 3 tonnes, bringing in US$43,000.

Sand mining in Uganda not only supplies the construction industry but also produces gravel used in various applications, including mixing with chicken feed, glass manufacturing, and water filtration in China. Chinese and Nigerian sand mining companies play a crucial role in this industry, with operators seeking specific types of sand that are graded, packed, and exported according to their requirements.

Interestingly, unlike sand for construction that is displayed to attract buyers, gravel has a specific market that remains a secret. Other actors in the illicit value chain of gravel in Uganda include local politicians, security personnel and brokers.

Local media in Uganda report that Ugandan sand is exported to China via the Busia and Malaba borders. It is packaged in large containers and “branded in a way that complies with the law,” suggesting that paperwork may be falsified to facilitate this environmental crime, notes the report.

In Kenya, Mango Tree Marine, an affiliate of Mango Tree Group was accused in 2021 of sand harvesting. According to the National Environmental Authority (NEMA), Kenya’s environmental management agency, the company’s operations in Mbita, Takawiri Island, Rusinga and Mfangano were found to be in ‘contravention of NEMA license.’

This was after a public outcry on the dredging activities and sand harvesting carried out by the company. Local-level sand harvesting in Kenya has been spurred by the construction boom along the Lake Basin counties of Kisumu, Kakamega, Busia, Bungoma, Kisii, Homabay and Migori. Many former fishermen have turned to sand harvesting due to a reduction of fish in the lake.

In one focus group discussion with BMU members from Usenge, Kenya, it was noted that sand harvesting along the shores and landing sites of Lake Victoria poses a great threat to the fishing industry since it destroys fish breeding sites.

Patrick Otuo, a socio-economic researcher at the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Resource Institute noted that the wanton targeting of large and mature Nile perch that are sexually mature has an effect on the viability of Nile Perch and other species.

Nelly Kerebi, a fish biologist at Kenya Fisheries Service told the online meeting that for a resource to be sustainable especially the fishery resource, its stock must be maintained and restored. But there is overfishing on the lake.

“There is an increased effort on the lake in terms of both mechanical and manpower effort,” she said. Kerebi noted that in the past years, most of the vessels involved in fishing in the lake were mainly paddle-driven or windsails but there is an improvement in technology and fisherfolk have moved to engine-powered vessels.

“We see an increase in manpower on the lake but also illegal, unreported and unregulated fishing which is one of the biggest issues in the lake. This is an issue of concern.”

As a result, Kerebi said, data collection is becoming a very big challenge. “The data is not getting to the agencies which are supposed to make informed or correct policies.”

From a fisheries perspective, sand harvesting causes siltation which causes destruction of breeding habitats of fish hence affecting the fish stock. She said fish maw trade is forcing the fishermen to target Nile perch more than any other species.

Timber smuggling too is rampant

Yet the fish sector is not the only sector suffering at the hands of environmental crime in the lake. The Lake Victoria islands such as Migingo (Kenya/Uganda), Remba (Kenya) and Koome (Tanzania) have become havens for the smuggling and trafficking of timber of various kinds. The Mukebu/drum tree (Cordia melenii) that is used for making boats is slowly becoming extinct on the Ugandan shores of Lake Victoria due to overharvesting.

As a result, boat makers now rely on smugglers to obtain the tree from the Democratic Republic of the Congo. Mahogany smuggling syndicates around the shores of Lake Victoria have also been noted in Busia County at the Kenya–Uganda border, from where it is taken to the port of Mombasa. Further, cases of arrests of smugglers of mahogany, podo and measopsis eminii timber from Uganda to Tanzania have also been noted.

Illicit charcoal trade

The Lake Victoria islands further serve as critical nodes for the illicit charcoal trade in East Africa with forests on Ugandan shores of Lake Victoria being the primary source of charcoal supplied to Kenya.

Local communities on these shores cut forest wood and make charcoal that is then transported by boat to Ugandan islands. Kenyan and Ugandan boats then cross the national boundaries to supply to wholesalers in Kenyan islands such as Remba.

From the Kenyan islands, the charcoal is then transported to retailer towns such as Migori and sold inland. The key actors in the illicit charcoal value chain therefore include local community members, businessmen, boat owners/transporters and local retailers who sell mostly to urban dwellers.

Charcoal from Uganda is supplied to Kenyan islands and distributed to towns such as Mbita, Migori, Homabay, Muhuru Bay and Sori. In April 2019, a Ugandan boat capsized near Bukasa Island in Kalangala District while smuggling charcoal to Kenya. The boat was allegedly overloaded with charcoal.

In July 2023, another Ugandan boat capsized near Kiseba islands in Kalangala District, killing 11 passengers. This boat was also overloaded with 100 bags of charcoal. The Ggaba market at the shores of Lake Victoria in Uganda seems to be a major distribution point for charcoal harvested from Koome Island.

The existence of cross-island networks of charcoal trade in Lake Victoria has also been established: Motor boats transport charcoal produced on Lake Victoria islands such as Koome in Uganda to the shore from where it is delivered to busy marketplaces such as Ggaba and Luzira in Kampala. The boats are manually loaded and unloaded by traders.

Dr. Okumu said environmental crimes in Lake Victoria thrive due to the readiness of actors willing to sustain the illicit markets in illegal fishing, sand harvesting and the charcoal trade, as well as the limited government presence and low probability of arrests in these spaces.

Possible solutions?

Going forward, the researchers call for the harmonization of the enforcement mechanisms used by Kenya, Uganda and Tanzania to enable them to cooperatively tackle transnational organised crimes, including environmental crimes such as the transit of charcoal, timber and illegal fishing in Lake Victoria.

They also call for the harmonization of, fishing regulations to ensure uniform compliance by fishermen in the lake. “This should include approved net sizes, fish sizes, fishing gear and penalties for non-compliance, they researchers say.

Besides reviewing and re-establishing an oversight mechanism over the operations and functions of BMUs to curb their complicity in the commission of transnational organised crimes in Lake Victoria, the researchers want the three East African countries to establish a modern and effective radar system to enhance information sharing, and security oversight in the ports and among security personnel and regional administrators in the lake.

“There is also urgent need for the gazetting of all islands in Lake Victoria to enhance the presence of border control officials and prevent the commission of transnational and environmental crimes.”

That should be followed by the development of a unified registration, identification and monitoring system for small vessels as they are the key conduits for the trafficking, smuggling and sale of fish on the lake.

Okumu noted that Lake Victoria appears to be suffering from a lack of strategic investments and this has contributed to the status quo on this lake. He said, Lake Victoria is a big resource and it is a good thing that the partner states are realizing its importance but it is important to recognize that as the economy grows it does so with environmental crimes.

Patrick Otuo, a socio-economic researcher at the Kenya Marine and Fisheries Resource Institute highlighted the importance of data science, regional cooperation and the deployment of technology (drones and live satellites) to improve monitoring of illegal activities in the lake.

Otuo called for increased enforcement, better data collection, and more significant penalties for offenders to safeguard Lake Victoria’s future. “We shouldn’t be having laws that are not enforceable,” he said.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price