By Eriasa S. Mukiibi

One issue that has preoccupied Ugandans since the launch of the East African common market is what they could sell to their regional counterparts in order to compete successfully. Dr. Bernabas Kiiza, an agricultural economist at Makerere University, believes the answer to this puzzling question is maize grain. He says that Uganda has the potential to reap windfall revenues from the crop since its regional counterparts have perennial food problems, yet their demand for maize is high and growing.

According to the World Food Programme, the UN agency responsible for global food security, 1.6 million Kenyans need food assistance this year, and it will take time for the country’s food situation to stabilize. Pastoralists and agro-pastoralists, and people in marginal agricultural areas, are particularly in dire need of food in Kenya. In many places, adds the WFP, the market price for maize is 70-80 per cent above the long-term average and many more millions are food insecure.

“Food prices have remained over 100 per cent higher than the December 2009 average levels in most of the pastoral districts,” notes the Kenya Food Security Outlook (KFSO) report, January-June 2010, prepared by USAID, Famine Early Warning Systems Network, the Kenyan Government and the UN World Food Programme.

Tanzania, another EAC partner, is also categorized as a food-deficit country with more than 40 percent of its 44 million people living in chronic food-deficit regions, where irregular rainfall causes recurring food shortages. In Burundi, only 28 per cent of the population is food-secure and as many as 50 percent of its people are chronically malnourished.

The WFP estimates average annual food deficits in Burundi range from 350,000 to over 450,000 metric tons (in cereal equivalent and after commercial imports and food assistance) against an annual average requirement of 1,718,000 tons, while food production has stagnated at pre-1993 levels. With a population growth rate of nearly three percent per year, per capita agricultural production in Burundi has declined by 24 per cent since 1993, adds the UN agency.

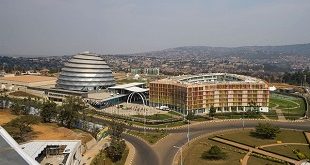

In Rwanda’s case, the WFP estimates that at least 22 per cent of households (2.2 million people) are food-insecure, and another 24 percent are highly vulnerable to food insecurity.

To alleviate these food deficits, the WFP has been procuring some of the food aid supplied in some regional countries from Uganda since 1991, with some of the food aid going to food-deficient Ugandans in the displaced people’s camps in northern Uganda, which have since been closed, Karamoja, and a few other disaster areas.

Since 2000, annual WFP food procurement in Uganda has increased from the initial 28,000 to 121,000 tons. Maize grain and meal, beans and Unimix (a maize meal-based blended fortified food) have been the focus of local procurement; 80 percent of purchases by weight are maize or maize based products, according to the WFP.

These developments, in Kiiza’s view, are a ray of hope for the Ugandan economy, which he says has enormous capacity to produce increasing amounts of maize grain to supply the WFP and to sell to regional countries and beyond if production and marketing constraints were dealt with. Annual maize grain production in Uganda has been steadily rising, according to the Uganda Bureau of Statistics (UBoS). Currently it is estimated to be between 500,000 and 750,000 metric tons.

The maize sub-sector is estimated to provide a livelihood for about two million Ugandan farm households, thousands of traders and several mill operators. The crop is a major source of income in the districts of Kapchorwa, Mbale, lganga, Masindi and Kasese with about 75-95 per cent marketable surplus, according to the UBoS.

Maize is a major export cereal that earned Uganda US$ 20.61m, $18m, $10.6m in 1995, 2001, 2002, respectively, contributing 10 percent of the value of agricultural exports in 2004, according to the ministry of finance, planning and economic development. Maize production contributes roughly 16 per cent of total cash and food crop contribution to Uganda’s national income. Uganda’s dependence on coffee as the main source of export income has declined over time, from a high of over 95 per cent in the 1980s to just 20 per cent by 2006, and the gap has been filled by non-traditional exports including maize.

However, maize growing is still dominated by subsistence level farmers with small land holdings (0.2, 0.5 ha), according to the ministry of agriculture, animal industry and fisheries. These small-scale farmers hardly use improved inputs and lack adequate post harvest equipment. Moreover, although they contribute to over 75 per cent of the marketable maize surplus, which is usually marketed on individual basis, they fetch low prices.

Andrew Mwesigwa is based in Kisenyi, a shanty Kampala area that is a hub for the trade. and has been involved in the maize grain trade for over a decade. He scours villages in almost all parts of Uganda for maize grain almost all year round. Since he collects the maize grain from farmer’s homes, he says, he has to pay them a price that enables him to operate at a profit.

The price he pays depends on the distance from Kampala. During bumper harvests, he usually buys a kilogram of dried maize grain for between Shs 120 and 200 in Iganga and Masindi, which he says are some of the most important producing areas. The price is lower in far-flung and harder-to-reach areas like Bundibugyo, where he says he at times pays shs 50 for a kilo of dried maize grain.

In Kampala, a kilogram of maize grain goes for an average of Shs 700, with maize flour costing about double that. In Nairobi, Kenya, a kilogram of maize flour costs the equivalent of Shs 4500.

Such a pricing system, or the lack of it, according to Kiiza, is what is crippling the maize grain industry and Uganda’s agriculture in general. He says there is need to build a strong public-private partnership that aims at improving the production, drying and marketing of maize.

Because maize farmers are disorganized and ill motivated, he says, their output is low and so is the standard of maize grain they produce. He argues that the Uganda National Bureau of Standards (UNBS) needs to be equipped to enforce maize grain standards better. “Some farmers dry the grain on the ground,” he says, adding that most of the grain they sell off is not of the right moisture content ” he explains that it is important for maize grain to be dried to the recommended moisture content to prevent it from going bad during storage or in transit.

Whereas the recommended moisture content should be between 10 and 13 per cent, he says, many farmers sell off grain of 20 per cent moisture content. Traders ride on farmer’s inadequacies to exploit them. Kiiza says that in one of his studies he discovered that traders buy grain cheaply, dry it, grade it, and sell it off expensively to buyers like the WFP or export it to Nairobi and other places, which are sometimes are as far as Zambia. Organization would enable farmers to acquire better drying techniques, equipment like moisture meters, which he says should be affordable.

All Finance Minister Syda Bbumba undertook to do according to her latest budget was to support 100 farmers per parish “by providing them with input kits consisting of seed, fertilizer and herbicide for selected enterprises such as rice, wheat, maize, tea, coffee and cocoa, and some implements such as hoes and spray pumps where they are needed”¦ The process of delivering these inputs and equipment has not yet started.

She also undertook to make arrangements for the provision of rice hullers, maize mills and other processing units at every sub-county for value addition in the medium term. President Yoweri Museveni has lately been talking about improving production and handling of maize grain by putting in place storage facilities and mills at every sub county, but nothing has yet been done to that effect.

Kiiza believes that government hasn’t sufficiently studied how to address the bottlenecks facing farmers and what potential there is for the maize crop in Uganda.

There has been an increase in the area planted with maize, production and quantity exported since 1990. The value of Uganda’s maize exports increased for the period 1990 to 1995, and then declined sharply to as low as US $ 2,437,000 in 2000. It had peaked in 1994, when it fetched US $ 28,666,000, according to the ministry of finance. In 2006, maize grain exports were worth US $ 24,114,000. However, observers believe there is much more potential for maize grain as an export crop given the regional realities and Uganda’s production capacity, currently estimated to be exploited by less than half.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price