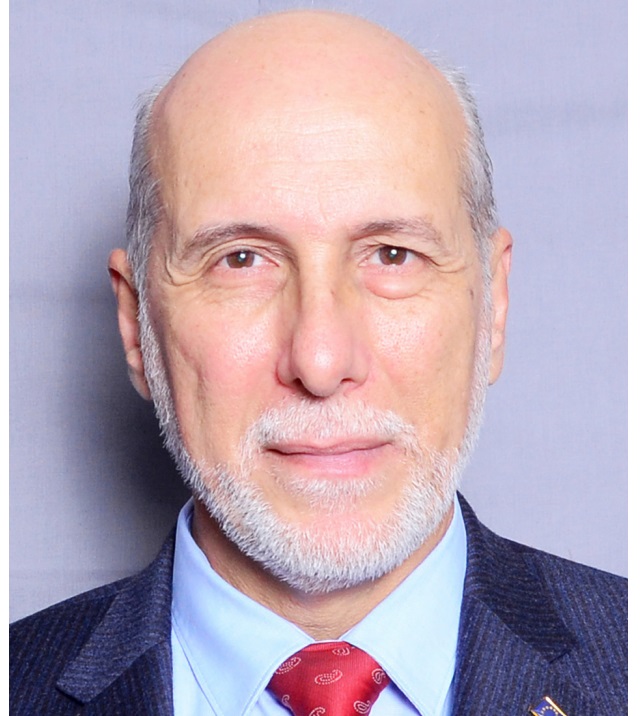

Last November, Attilio Pacifici, the head of the EU Delegation in Uganda led seven other ambassadors from France, Belgium, Germany, Italy, Sweden, Denmark and Austria on a mission to western and northern Uganda to have firsthand experience of the level of pressure Uganda’s natural resource assets such as Bugoma forest (Hoima District) and Zoka forest (Adjumani District) are currently facing. In an email interview, Pacifici told The Independent’s Ronald Musoke why the mission was important.

What were your impressions when you visited some of these forests during your expedition?

This visit was a joint mission to the west and north of Uganda where we had the chance to visit iconic forests like Bugoma and Zoka but also national parks like Murchison Falls. During this mission, we were honoured with the participation of high-level government officials and we had the opportunity to jointly exchange with very committed civil society actors on the ground. The visit demonstrated the risks faced by some of the last protected forests in Uganda and the need to step up efforts to protect them and preserve the ecosystem services they provide. Our main message was and remains that development can and needs to go hand in hand with environmental conservation. Conservation has a strong economic value, which needs to be promoted, and we are here to support this agenda. That is why in all our engagement, we have stressed the importance of striking the right balance between environmental protection and economic development.

I know you are aware from what you saw that deforestation is happening at an alarming rate across the country, even when the country has robust laws governing forests. What, in your opinion, will it take to control this problem?

Tackling the challenge of deforestation will require a holistic approach and high level of commitment from governments, development partners, private sector, civil society organisations, the media, ordinary citizens; all of us. I am sure you know that already Uganda’s forest cover has plummeted from 24% of its area in 1990 to about 12.5% today. This is a big challenge that requires collective action. It is also important that government should provide strong, consistent and broad support to the forest management authorities and the law enforcement agencies. For one, we have to make the natural forests untouchable in every sense of the word. We have to make the traditional sources of biomass energy very expensive while ensuring that alternative sources of clean energy are made available and cheaper to meet the most basic household needs. Once degraded, the cost of restoring a natural forest is colossal. It is not as easy as planting a couple of trees because as you know in Uganda the natural forests have historically had vast and varied species unlike in Europe where the species are limited. At a regional level, a formal mechanism should be established, to regulate cross-border trade and movement of forest products in the region. The problem of unregulated trans-boundary forest management and trade has resulted into forest products illegally acquired from one country being a legal import in the receiving country. This makes it difficult to regulate trade in forest products.

The EU has been supporting a project called the SPGS as one of the possible mechanisms to grow back and also conserve Uganda’s forests. Looking at the rate of deforestation that has been inflicted on the country’s forests over the last 16 years (since 2004 when this scheme began) vis a vis the trees that have been planted, how would you rate the success of this project?

The Sawlog Production Grant Scheme (SPGS) has been implemented in Uganda over the last 16 years supporting the establishment of over 80,000 hectares of quality commercial plantations and woodlots across the country. In terms of contribution to the forest cover vis-avis deforestation, SPGS contribution remains limited. However, the main objective of the SPGS project is to promote quality wood products and ensure that plantations are managed to provide saw logs for timber, building and utility poles, and fuel wood. Providing alternative sources of wood from fast growing tree plantations is a way of reducing pressure on natural forests on both private land and Central Forest Reserves (CFR) but it is not an end in itself. Our support has been fundamental in creating a critical mass of plantations that provide valuable raw materials for industries and generate rural jobs. The plantations have been established in deforested areas complying with international sustainability practices. SPGS is now a model which is being replicated in many other countries such as Rwanda and the DR Congo. Today, most of the industrial wood used in Uganda is sourced from plantations – and this has played a leading role in reducing the pressure from natural forests. But this is not enough. Protection of natural forests cannot be substituted with establishing commercial plantations of a few tree species, as is currently the case. We have to make sure that the natural forests—what is left of them—is untouchable.

What is your opinion in regards to some conservation experts who think monocropped forests are a defective idea of forest restoration?

My personal view is that this is an inevitable evil. However, monocultures as such need not be a problem – provided that they are not large contiguous areas and are part of carefully designed sustainable landscapes that include areas for conservation of biodiversity. Even at large-scale, the plantations can be fine when they are established in a mosaic manner with ecological corridors improving the conservation function.

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price