New Novartis study shows why countries will miss malaria eradication targets despite successful prevention campaigns

Kampala, Uganda | FLAVIA NASSAKA | Malaria figures in Uganda are alarming; with 2017 Ministry of Health statistics showing the disease still claims about 80,000 lives per year, equivalent to an average of 200 people every day – enough to fill 14 taxi vans that seat 14 passengers each.

Between 20 and 23% of those dying from malaria are children under the age of five. That is about 40 children in this cohort dying every day.

Malaria also accounts for 25 to 40% of sick people going to health facilities, 20% of all sick people who are admitted, and 9-14% of patients who are admitted in health facilities for all diseases and end up dying.

However, what is happening in Uganda seems to be happening in other countries too, according to a new report by independent policy researchers commissioned by Novartis, the health care company that launched fixed-dose artemisinin-based combination therapies, and released on April 17 in London. The new study, Malaria Futures for Africa, or MalaFa, reveals what malaria experts in Africa actually think about progress and challenges towards malaria elimination.

The MalaFa report, released during the recent Commonwealth Heads of Government Meeting in London, captured thoughts of 68 malaria experts from 14 sub- Saharan African countries. The respondents including ministers of health, members of parliament, senior civil servants working in health, heads of national malaria control programmes and representatives of academia were picked from high malaria prevalence countries of Uganda, Kenya, Senegal, Ethiopia, Mozambique, Ghana, Burkina Faso, Malawi, Mali and Cote d’Ivoire among others.

The interviewees were engaged in face to face interviews between December 2017 and February and questioned about how ready their countries are in terms of policy and meeting 2030 malaria targets. They also answered queries on priorities for prevention and treatment, raising threats, any new tools being developed to respond to the malaria threat, and any operational research agenda.

Missed targets

According to the report, respondents held mixed feelings on the likelihood of meeting the World Health Organisation 2030 target of eliminating malaria.

While respondents in Senegal, Ethiopia, Mozambique and Namibia were very positive about their progress in the fight against malaria, those in Uganda and Kenya were skeptical; especially if the status quo is maintained.

Over three quarters of the respondents were alarmed about the potential impact of resistance on current prevention methods and treatments and the impact this might have on reducing transmission.

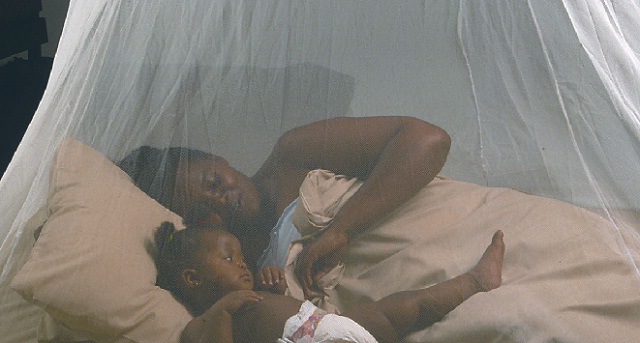

The MalaFa report notes that the decreasing incidence of malaria thanks to use of bed nets and other interventions may have made people complacent and that they now do not use the tools as well as they should. As a result, the success of the prevention campaigns appears to have led to a decline in use of prevention tools, such as bed nets.

Uganda recently completed a year-long campaign from February 2017 to distribute up to 27 million bed nets free of charge, covering 85% of the population, and at a cost of Shs97 billion. Dubbed the “Chase Malaria” campaign, it ended on Mar. 17 with a ceremony in Sheema in western Uganda.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price