How safe is Uganda from so-called `coup contagion’?

COVER STORY | IAN KATUSIIME | In a paper published in The Journal of Conflict Resolution entitled `The “Coup Contagion” Hypothesis’, two professors; Richard P.Y. Li and William R. Thompson, popularised the expression as far back as 1975. They wrote that their “statistical evidence indicates that the occurrence of earlier coups does affect the subsequent probability of coups elsewhere”.

They called their speculative interpretation “coup contagion”, a phenomenon which emphasises the possibility of behavioral reinforcement processes operating within global and regional communication networks.

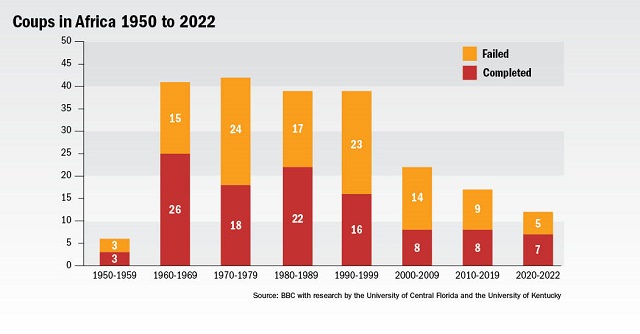

Since the Aug. 30 military coup in Gabon, which was the 8th in a slew of military coup d’état on the African continent in two years since 2021, the phrase has been repeated in news headlines and commentary across the equally.

The `coup contagion’ theory has been partly debunked but that has not stopped widespread reference to it in the aftermath of recent coups.

When Economic Community of West African States (ECOWAS) held an emergency summit in Accra, Ghana, in February 2022 to discuss the coups, ECOWAS Chairman and Ghanaian President Nana Akufo-Addo said coups had become “contagious” and that the trend “must be contained before it devastates our whole region”.

But writing in the October 2022 edition of the Journal of Democracy, Naunihal Singh; the American political scientist and author of `Seizing Power: The Strategic Logic of Military Coups’ (2014), gave the phenomenon a new interpretation. In his view, the recent flurry of coup activity reveals that post–Cold War norms against coups have eroded and will likely continue to get weaker, making a return to post-Cold war levels of coup activity unlikely.

“The recent spate of coups and coup attempts six successful and three failed attempts in the span of twelve months is not an indication that coup activity will return to the high levels seen during the Cold War.

“There is no evidence of a contagious wave; what we are seeing is simply the coincidence of already coup-prone countries (mainly in Africa) having coup attempts in the same period. These attempts were also not driven by increased insurgent activity or by western training of these militaries.

With the back and forth as a background, every military-related incident on the African continent has gained renewed poignancy in the context of the coup.

That is possibly why Rwandan President Paul Kagame’s Aug.30 announcement of a decision to approve the retirement of 12 military generals has attracted a lot of international attention and speculation.

The retirement approval was for 83 senior officers, six junior officers and 86 senior noncommissioned officer, 678 whose contracts ended and 160 medical discharges.

But the focus has been on two four-star generals, James Kabarebe and Fred Ibingira and two three-star generals, Charles Kayonga and Frank Mushyo Kamanzi who have been retired.

Kabarebe and Kayonga were previously Chief of Defence Staff of Rwanda Defense Forces (RDF). Kabarebe is a former Minister of Defense and has been Senior Presidential Advisor on Defence and Security.

Others on the list are major generals Martin Nzaramba, Eric Murokore, Augustin Turagara, Charles Karamba and Albert Murasira and brigadier generals Chris Murari, Didace Ndahiro and Emmanuel Ndahiro.

A day after the Rwandan retirements were announced, the government of the 90-year old Paul Biya issued a decree immediately removing several top officers from their positions.

President Biya who has been in power for 48 years since 1975, reportedly appointed new leaders of the security forces including Ajeagah Njei Felix, Kamdom Lucas, and Nguema Ondo Bertin Bourger.

There is no indication that the changes in Rwanda and Cameroon were connected to the recent slew of coups. In fact, around the same time on Sept.31, President Museveni saw off 11 generals who officially retired from active service of the Uganda Army.

But the intense focus on African militaries derives partly from the central role they play in upholding authoritarian governments.

Many post-independence African politicians have gone to great lengths to secure military loyalty, often counterbalancing rival forces, personalising command hierarchies, ethnically stacking both the regular military and presidential guard, and providing extensive patronage benefits to soldiers.

As speculators have been scouring over the perceived vulnerability to similar coups in African countries, some have pointed out what they say are similarities in the circumstances that precipitated the coup in Gabon and the on-going maneuvering around the inevitable succession of President Yoweri Museveni who has ruled Uganda for 37 years and will be 80 years old in a few months.

Equally ubiquitous in the post- Gabon coup media blitz has been the reference to the ‘Bongo dynasty’ which had held power in that country for 56 years until the morning of Aug. 30 when military officers announced on television that they had seized power.

Significantly, the end of more than half a century of family rule came just days after a presidential election where the now overthrown Ali Bongo had been declared winner with 64%.

The deposed Ali Bongo succeeded his father, Omar Bongo Ondimba who had ruled Gabon from 1967 to 2009.

Museveni has equally been accused of entrenching “family rule” in Uganda. His younger brother, Gen. Calen Akandwanaho, is also a powerful figure in the government and his and his wife is the minister of Education and Sports and has served in cabinet for 14 years. Museveni also has a powerful son in-law, Odrek Rwabwogo, Who was recently the beneficiary of a staggering Shs37bn to promote coffee through his Presidential Advisory Committee on Exports and Industrial Development, an informal outfit that got the money through a classified budgetary allocation.

Speculation has been rife that Museveni’s son, Gen. Muhoozi Kainerugaba, who has recently held numerous meet-the-people events, is positioning himself to succeed his father in the event. Some of the General’s supporters have referred to him as “a standby generator”.

At an event in September last year, Balaam Barugahaara, referred to the First Son as a “standby generator” amid frenzied MK campaign activities.

“If you touch Mzee (Museveni), we have an avenger. So I belong to those millions of avengers. We are not competing with you, we work with you and we shall wait for your guidance for when we can shoot,” Balam told Museveni at the event where the president was the chief guest.

Some have dared him to take the path of “courageous officers” carrying out coups. One of those who has constantly furnished him with that advice is Yusuf Serunkuma, a columnist with The Observer who describes himself as a political theorist.

“What then remains of Gen. Muhoozi if he ever wanted the presidency? The prophecy: as a good soldier, he is the most qualified to coup his father. This is his only assured window. In fact, if he successfully court-martials his father, or even symbolically jails him, that would complete his transformation from villain to hero,” he wrote.

But coups are complex and disruptive events, according to an analysis in the Africa Defense Forum, a publication that exclusively reports on the African militaries. In an article titled “Why Are Military Coups Returning to Africa?” said, however, that understanding what causes coups is the first step in building professional militaries that have the knowledge, training and desire to avoid them.

The article noted that history has shown that once coups take root in a country, it tends to be easier for them to reoccur. It said researchers have studied the phenomenon and given it a name: the “coup trap.”

Uganda has had, at least one successful coup in 1971 when Gen. Idi Amin Dada deposed then then elected leader, President Milton Obote. But there have been numerous attempts at military coups and the country, which has had nine different administrations since it attained independence in 1962, has never had a significant peaceful transfer of power. As the saying goes, they all come in by the gun and are kicked out by the gun.

In March 2013, for example, a clique of soldiers attacked Mbuya military barracks, the UPDF headquarters. The incident was seen by some to be a coup attempt against President Museveni although it was nipped in the bud. The suspected soldiers were arrested and convicted by the court martial but the actual coup plotters remained a mystery.

A few months after the incident, in June 2013, Museveni made reshuffled the army top brass. Gen Aronda Nyakairima was dropped as CDF and appointed minister for internal affairs. Gen. Katumba Wamala replaced him.

Equally, in March 2022, Hakeem Onapajo, a Senior Lecturer in the Department of Political Science & International Relations at the Nile University of Nigeria, said in an interview with Institut Montaigne; an independent French think tank that the coups were a result of “disenchanted with the idea of democracy itself”.

He explained that Africa’s democratic struggles in the 1970s and 1980s promised that democracy would bring security and development and end corruption and poverty and improve human rights and civil liberties, and rule of law better than the military.

“Unfortunately, about three decades into the democratic journey, nothing substantial has changed,” he said, “The masses – particularly the youth – feel excluded from policy discussions, and have become increasingly disenchanted with the idea of democracy itself, if this is all that it can offer.”

He said these sentiments provide an enabling environment for the military to successfully stage coups in West African states, a phenomenon that “has become increasingly welcomed by civilians”.

“This reaction reflects the masses’ lack of faith in political institutions ruled by corrupt elites who have long ruled their countries,” he said.

He also blamed politicians who maintain strong military structures with the aim of using them to have full control of the political space. He also mentioned ethnic domination.

Dr. Besigye on coups

As Ugandans pondered on the events in Gabon, an oil-rich country with a population of just 2 million, with glee and excitement, Dr. Kizza Besigye, a veteran politician who has stood against Museveni in four elections and kept Museveni’s feet to the fire, had some choice words: violent overthrow is not the solution.

“Those who are victorious by the gun become the new problem,” Dr. Besigye was speaking at a Kawanga Ssemogerere legacy conference at Hotel Africana on Aug. 29 just a day before the coup in Gabon.

Ssemogerere stood against Museveni in 1996 in the first elections organised under Museveni’s government. He was a longtime leader of the Democratic Party although the government had banned political parties when he stood.

Besigye narrated that when he fled Uganda in 1981, it was from gunmen but things quickly turned around. “I was victorious in entering Kampala in January 1986 with the guns that had chased me. A short while later, I was crossing the same border running away from the same guns that I had arrived with a short while earlier,” he said in his typical wry laughter.

Besigye ran into exile in 2001 after his first election challenging Museveni that was marred by violence and rigging. He had been part of those who fought in the bush war that brought Museveni to power.

“I would like to persuade and convince those who would like to pursue that route that it should not be our mission,” Besigye said. The following day however Ugandans reacted with euphoria at the coup in Gabon that kicked out Ali Bongo, a scion of dictatorial rule that many have likened to Uganda.

Since then, according to a Premium Times story, Nigeria’s President Bola Tinubu has called the flurry of coups in Western Africa an “autocratic contagion” and vowed to work with other heads of state to defend democracy.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price