How pride, Kabagambe’s ghost, and Chinese investors sealed his fate

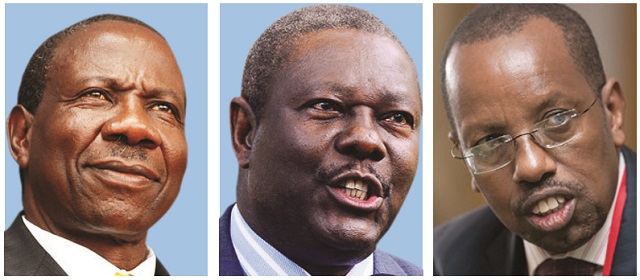

Kampala, Uganda | HAGGAI MATSIKO | On July 03, the sacked former Permanent Secretary of the Ministry of Energy, Stephen Isabalija swung the first blow in a fight that would live him jobless. He unilaterally cancelled an MoU the government had entered with China Africa Investment and Development Company (CAIDC), which is seen as a major potential funder for President Yoweri Museveni’s infrastructure projects.

It was a bold move because the Chinese lobby is the most powerful in Uganda. The Energy Minister, Irene Muloni and Minister of State for Energy, Simon D’Ujanga who ordinarily should have handled the issue, were not impressed. Neither were the Chinese lobbyists. Soon, a report about the implications of the move were on Museveni’s desk. Insiders say this report was one of the several the president had received about Isabalija since he appointed him the Energy Ministry PS in November last year.

Back then when Isabalija joined the ministry with the full force of President Museveni, Muloni, D’Ujanga and the technocrats at Amber House were smart enough not to enter a direct fight with him. He was seen as almost untouchable.

As a result, critics say, since being parachuted to the powerful position, Isabalija behaved as if he was a one man army in the ministry. In another fight, he had taken on Muloni and several officials at the Energy Ministry over the US$4 billion oil refinery deal. This is President Museveni’s pet project and it also involved Isabalija taking on the Chinese. Oil deals are murky and it is rarely clear which deal is cleaner than the other. So denouncing the Chinese in favour of the Americans might not have been Isabalija’s undoing. What is clear is that when he fired Isabalija on Aug. 23, Museveni was terribly disappointed in him. He had pinned a lot of hope for reforming the Ministry in him.

Significantly, Museveni did not even try to sugar-coat the sacking by posting Isabalija to some vague posting anywhere. Instead, the president directed that he should be given a one-month salary in lieu of his termination.

Sector insiders say they are not surprised by Isabalija fumble and fall. He had been appointed in an ad hoc way to a sensitive sector and was kicked out in equal ad hoc fashion.

As if to rub Isabalija’s face in the dust of defeat, Museveni appointed former PS Kabagambe Kaliisa’s protégé, Robert Kasande, as acting PS. By the time Kaliisa left, he had appointed Kasande as director Petroleum Directorate and the talk around the ministry was that Kaliisa had been grooming him to be his successor. It appears that while Isabalija came with the full force of the president’s backing, he forgot that he had some serious heavy lifting to do to win him the hearts that he badly needed to adapt and survive as a new comer at Amber House and in the entire civil service. His first directive on the job did the exact opposite.

Isabalija’s problems

When Isabalija arrived at the Energy Ministry head office, Amber House, soon after he was appointed, his first directive might have been anticipated. After all, most new bosses order changes to their new office. But the scale of the remodeling Isabalija ordered raised a few eye-brows.

The Amber House building that Isabalija was moving into is a colonial era building with tiny office cubicles with narrow windows, low ceilings, and poorly lit corridors. He wanted his office bigger and grander.

So it was whispered that the new PS wanted to improve the office to the standards of the one he previously occupied on Level 1, Victoria Towers, Plot 1-13, Jinja Road, as the Vice Chancellor of Victoria University. The expansive office had wide windows with a view of the city’s main road and the eye-catching architecture of blocks like Social Security House across the street.

But others read another motive in Isabalija’s move.

“If Kaliisa, highly respected across the ministry and highly experienced in everything energy having built the different units from scratch could work in that office,” an official at the ministry asked, “who was Isabalija not to?”

Isabalija and his predecessor, Kabagambe Kaliisa had fallen out so much that there was no official handover.

They said he wanted to expunge any traces of Kaliisa, whom he was replacing after a bruising tussle. Kaliisa had spent 40 years, half of which he was in top positions at the Energy ministry and had appeared unshakeable. Kaliisa, who was the archetypical geologist, traced it to his family—his grandfather had owned a salt mine— and on joining the ministry in 1976 after graduating with Honours in Geology and Chemistry from Makerere University, that same year, Kaliisa said he discovered 12 million tonnes of gypsum, a mineral used in the making of cement in Semiliki and three years later, 30 million tonnes of Marble in Moyo District.

His office had for years remained ordinary with the major decorations being rocks of mineral samples—some of which he had discovered and others by the teams of geologist he led.

Over the years, Kaliisa, who would later acquire a Masters of Science in Petroleum Development Geology from Aberdeen University, had led so many teams that not only delivered all the laws and regulations that govern the sector, his teams laid the ground work for almost all energy infrastructure projects in the mining, oil and gas and energy sectors.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Hi independent.co.ug Webmaster, exact same in this article: Link Text