According to those in the know, identifying the participants for such a major diplomatic gathering is a complicated process, and settling on the final summit list was more a product of bureaucratic and interagency sausage making than anything more sublime. What considerations were at play?

First, regional dynamics played a big role. Take the Middle East. Looking strictly at the democracy index numbers, the only two countries that could plausibly make a bid for participation are Israel and Tunisia. Unfortunately, Tunisia is experiencing a slow-motion coup, and the optics of having Israel attend as the sole representative from the Middle East was a nonstarter. In that context, enter Iraq—just democratic enough to score an invite, but nobody’s idea of enlightened leadership.

Second, broader U.S. strategic interests also mattered. Pakistan, the Philippines, and Ukraine are all flawed democracies with endemic corruption and rule of law abuses. Yet they are important partners of the United States—whether to counterbalance Chinese influence (Philippines), withstand Russian encroachment (Ukraine), or assist with counterterrorism (Pakistan). Undoubtedly, the State Department’s relevant regional bureaus made the case on those grounds.

Finally, something akin to a democratic do-no-harm test played a role in certain cases. For example, the administration’s exclusion of Hungary and Turkey may have been based on Biden’s reluctance to do anything to help the reelection chances of Hungarian Prime Minister Victor Orbán or Turkish President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan.

If bureaucratic wrangling largely was responsible for deciding which countries made it onto the summit list, what insights, if any, can be gleaned from the invite list?

First, reform-minded leadership helped nudge several borderline countries onto the list. Positive trajectories in Angola, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, and Zambia, for example, were enough to overcome their low performance scores.

Also, upcoming elections with the potential for big leadership changes were a factor. The Philippines and Kenya face contentious national elections in 2022, and Biden’s team may have hoped that summit engagement can positively reinforce their political transitions.

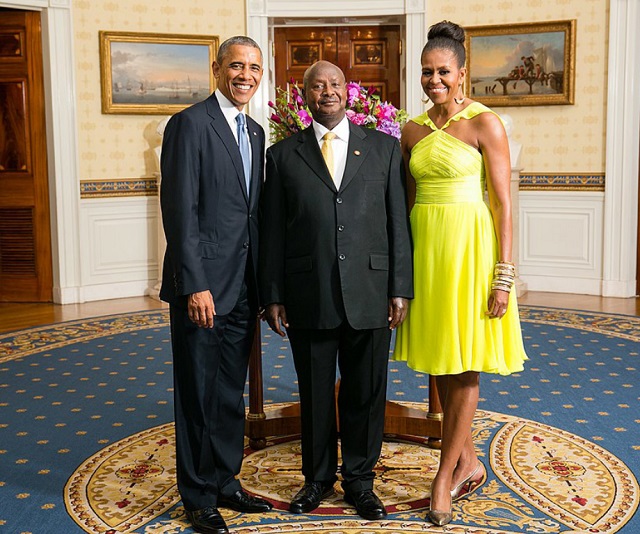

In the case of Kenya, the country’s significance is also elevated due to ongoing crises in Ethiopia and Sudan. This is where Museveni previously held all the cards.

Big democracies generally received a pass, notwithstanding troubling reversals on individual rights and freedoms. Brazil, India, Indonesia, Nigeria, and Pakistan are experiencing serious democratic backsliding, populist politics, and regular political violence. But they also have large populations, are important regional economies, and exert considerable influence on the international stage.

The Africa leaders summits

- Tokyo International Conference on African Development (TICAD) every five years. Next scheduled for 2022.

- Africa-France summit every year.

- Forum on China–Africa Cooperation (FOCAC). Held in China or in Africa every three years.

- India-Africa Forum Summit (IAFS)

- Russia-Africa Summit . Next is 2022.

The 17 African nations invited to the Democracy summit are:

- Angola

- Botswana

- Cabo Verde

- Democratic Republic of Congo

- Ghana

- Kenya

- Liberia

- Malawi

- Mauritius

- Namibia

- Niger

- Nigeria

- Sao Tome and Principe

- Senegal

- Seychelles

- South Africa

- Zambia

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

Is really usa a democratic nation with all mass killings of blacks by us cops?

Why dont their majority vote determine the winner? I think they shouldnt be lecturers of democracy.