Is Education ministry aborting morality to please donors?

Kampala, Uganda | MUBATSI ASINJA HABATI | Two weeks before Uganda ended the longest school closure in the world owing to outbreak of COVID-19 pandemic, the Ministry of Education and Sports instructed all primary and secondary schools to allow pregnant students to return to school so as to complete their education.

With funding from donors, such as the United Nations Children’s Fund (UNICEF) and the United Nations Population Fund (UNFPA), Uganda’s Ministry of Education and Sports issued a 40-page “revised guidelines for prevention and management of pregnancy in school settings”.

Among these guidelines is the rationale that education is a right and “there is need for change in attitudes towards pregnant girls, their contribution in school, and subsequent re-entry to school. These attitudes are gender-biased, violate the girl child’s right to education.”

The donor UN agencies that deal with children and reproductive health have been campaigning across Africa for states to change their stance on treating girls who become pregnant while in school.

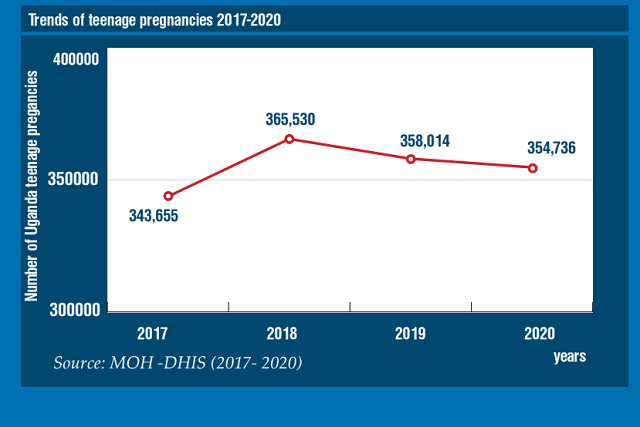

For several years, Uganda has been running a policy that does not allow pregnant girls in school. The effects of COVID-19 pandemic left over 354,736 school girls impregnated in 2020 and by June 2021 at least 196,499 teenage girls had become pregnant.

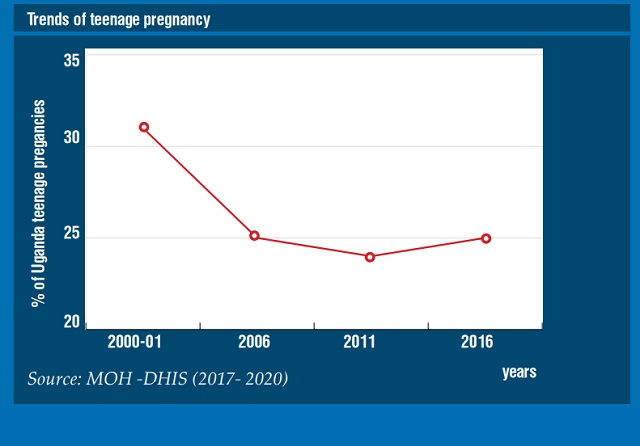

The Uganda Demographic and Health Survey of 2016 done by Uganda Bureau of Statistics says 1 in 4 adolescent girls aged 15 -19 are already mothers or are pregnant with their first child while 64% girls have sex before the age 18. Teenage childbearing is higher in rural areas at 27% than in urban areas (19%).

18% of the annual births in Uganda are as a result of teenage pregnancy according to a document by UNICEF and UNFPA) titled “Teenage Pregnancy in Uganda: The Cost of Inaction” published on Jan.14, 2022.

It says if no action is taken to end teenage pregnancy, about 64% of teenage mothers will not complete primary education level, 60% of teenage mothers will end up in peasant agriculture work and annually more than Shs645 billion will be spent by Government of Uganda on healthcare for teen mothers and education of their children.

These startling statistics and donor campaigns such as ‘keep girls in school’ contributed to a policy shift to allow pregnant girls in school.

Campaigners like UNFPA and UNICEF are talking up a spike in teenage pregnancies. They say a breakage of the social protection net that schools offer since COVID-19 when Uganda imposed the longest closure of schools in the world exposed girls to the risks of sexual violence, exploitation and abuse.

Uganda has for years recorded some of the highest teenage pregnancy rates in the world, according to the United Nations. Each year, thousands of school girls become pregnant at the time when they should attain education. Adolescent girls who have early and unintended pregnancies face many social and financial barriers to continuing with formal education.

According to the UNFPA Uganda Fact Sheet on Teenage Pregnancy 2021, 290,219 pregnancies were recorded in Uganda from January to September 2021. That is an average of 32,000 teenage pregnancies per month; a 7% jump from the average 29,835 teenage pregnancies per month recorded before COVID-19 and school closure in 2019.

Uganda criticised

In a report published on September 29, 2021 titled `Rights Progress for Pregnant Students’, Human Rights Watch listed Uganda among five more Sub-Saharan countries that have acted to protect girls.

It said since 2019, at least five sub-Saharan African countries; Mozambique, Zimbabwe, Sierra Leone, Uganda, and São Tomé e Príncipe – have either revoked restrictive or discriminatory policies or adopted laws or policies that allow pregnant students and adolescent mothers to stay in school under certain conditions.

It cited the revised guidelines on pregnancy prevention and management in schools that Uganda issued first in December 2020. It said the guidelines do not go far enough as they “place numerous conditions on enrollment”, including setting “strict” reentry” conditions, including requiring girls to drop out when they are three-months pregnant, and to take a mandatory six-month maternity leave.

Human Rights Watch said it had previously found that some of these conditions constitute an effective barrier, particularly as girls will be required to stay out of school for up to a year.

“The policy relies on effectively compulsory periodic pregnancy testing to detect and prevent pregnancies, violating girls’ rights to privacy, equality, and bodily autonomy,” it said.

Previously, the policy has been to allow finalist pregnant girls sit for their national exams but not study alongside other children. Even then, girls who fell pregnant often dropped out of school, as the “old” government guidance required them to withdraw from when they are three months pregnant until six months after giving birth.

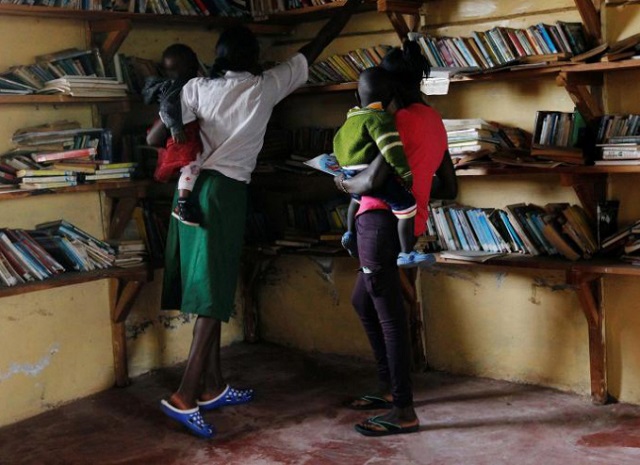

While the government has a policy that allows pregnant learners to continue with their studies after delivering, in the past, schools have been quick to chase learners who are discovered to be pregnant. Consequently, many of them struggle to return to school at all due to barriers like social stigma, lack of childcare or financial support.

Policy change

Now policymakers say that schools must allow pregnant students to continue learning even if they are expecting. Uganda’s State Minister for Higher Education, John Chrysostom Muyingo, said it is a government directive that all children should go back to school whether pregnant or breastfeeding.

However, some teachers find the directive unrealistic. They say teaching pregnant students might be very complicated.

“We do not want that learner to associate with others. We fear her to associate with other learners, she will share what happened and the others will also try. The learners will look at her like she is spoilt. She cannot be free at school,” says one teacher in a government-aided primary school in Wakiso District.

Ezra Bukundika, a secondary school teacher, says the education sector in Uganda is under trial because of the new guidelines.

“The entire education system is now lacking in terms of desired outcomes, desired expectations, desired value standards and desired ethics to uphold,” he says.

According to him, “it’s getting extremely hard for a teacher on to whether he should promote values of sex before marriage or to whether he emphasises parenting skills”.

“The policy guidelines focus at only meeting interests of the donors, not education for social transformation and moral building,” he says.

Bukundika argues that a pregnant student is a mother in waiting, which state requires frequent review and one that already has marital obligations to the father of the baby to be born.

“Do schools have facilities that will accommodate this pregnant student? Do schools have provisions for how this pregnant student will freely interact with the father to the child? Will the school timetable accommodate antenatal reviews? How will this mother be maintained in school with less stigma? How will government that owns less than 20% of the schools, influence strong foundation bodies, whose religious ethos can’t accommodate such case scenarios?”

He advises that: “As a post COVID-19 pandemic intervention, the ministry would have gazetted specific schools to handle girl children that got pregnant during the pandemic, just as we have schools for special needs children.

“Short of this, the country is yet to witness more drama, and paradox of student discipline versus managing victims for sexual promiscuity.”

He says the special schools would be equipped with all facilities for antenatal services, teachers would be retooled with basic health training, and a special timetable would be designed that accommodates pregnant conditions as well as the education demands.

That is the model of Serene Haven secondary school in Kenya which enrols pregnant girls and teenage mothers with their babies.

Edward Kanoonya, the head teacher of Kololo Secondary School says that at times, it’s the students who are more scared of being in school. “We might be willing to have the students come back but often it’s them who hide and even avoid coming back,” he said. “They are ashamed and would rather go to another school where they are unknown than coming back and continue studying while pregnant among their friends,” he said.

Two bishops have also come out to oppose the government policy shift that now allows pregnant and breastfeeding girls to be in school. On 18 January, the Bishop of Ruwenzori Diocese Rev. Reuben Kisembo said he is against allowing pregnant and breastfeeding students back to school. “We advise that let them first give birth, breastfeed and later they can come back to school. They set a bad example to the rest of the girls in school,” Bishop Kisembo said.

Bishop Kisembo joins Bishop James Ssebagala of Mukono Diocese who on January 8, directed teachers in Church of Uganda-founded schools to block pregnant or breastfeeding girls from their institutions, just two days before the schools reopened. Bishop Ssebagala said although it is good for parents to support girls who are pregnant, it was not morally upright to allow them to sit in class with other children.

“All head teachers, I want to tell you that we shall not allow pregnant or breastfeeding girls in class. When all girls turn up, carry out the usual medical examination so that those found pregnant can go back and give birth.They will come back after giving birth,” the bishop said.

“Imagine someone saying even breastfeeding ones should be allowed to attend class. No, this we shall not accept because our schools were started purposely not only to impart knowledge but also discipline in children. How can a teacher be teaching when a girl is giving breasts to her child?” Bishop Ssebagala wondered.

Moral dilemma

This is the moral dilemma campaigners for inclusive and leave no girl behind in education have been citing for long. A report by the international NGO Human Rights Watch says all girls have a right to education regardless of their pregnancy, marital, or motherhood status.

“The right of pregnant—and sometimes married—girls to continue their education has evoked emotionally charged discussions across African Union member states in recent years. These debates often focus on arguments around “morality,” that pregnancy outside wedlock is morally wrong, emanating from personal opinions and experiences, and wide-ranging interpretations of religious teachings about sex outside of marriage. The effect of this discourse is that pregnant girls – and to a smaller extent, school boys who impregnate girls– have faced all kinds of punishments, including discriminatory practices that deny girls the enjoyment of their right to education,” reads part of the report titled ‘Adolescent Pregnancy and Girls’ Education in Africa’.

In 2013, all the countries that make up the African Union (AU) adopted Agenda 2063, a continent-wide economic and social development strategy. Under this strategy, African governments committed to build Africa’s “human capital,” which it terms “its most precious resource,” through sustained investments in education, including “elimination of gender disparities at all levels of education.”

“Two years after the adoption of Agenda 2063, African governments joined other countries in adopting the United Nations Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), a development agenda whose focus is to ensure that “no one is left behind,” including a promise to ensure inclusive and quality education for all. African governments have also adopted ambitious goals to end child marriage, introduce comprehensive sexuality and reproductive health education, and address the very high rates of teenage pregnancy across the continent that negatively affect girls’ education,” reads part of the Human Rights Watch report.

It concludes that: “Leaving pregnant girls and adolescent mothers behind is harmful to the continent’s development. Leaving no one behind means that African governments should recommit to their inclusive development goals and human rights obligations toward all children, and ensure they adopt human rights compliant policies at the national and local levels to protect pregnant and adolescent mothers’ right to education. Early and unintended pregnancies jeopardise educational attainment for thousands of girls. For this reason, governments need to prevent them by ensuring their educational institutions provide knowledge, information, and skills, so that pregnant girls and adolescent mothers can enjoy their right to continue their education.”

Commenting on the bishop’s remarks, the State Minister for Higher Education, John Chrysostom Muyingo, said it is a government directive that all children should go back to school whether pregnant or breastfeeding.

“It seems my friend the bishop doesn’t know the position of government. I will go to his office and talk to him. I know he will understand my explanation and change his position,” Minister Muyingo said.

Delphine Tumusiime Mugisha, the country director of Raising Voices, a child rights NGO, says that parents should use this opportunity to give their second daughters a second chance that would ordinarily not be there.

“We are giving parents a chance to allow the children to come back to school. The senior women and men have been trained to counsel them, and counsel the others to be supportive. The school, will be a safe environment, so we are appealing to all parents not to withhold but give a second chance to these young girls,” said Delphine Tumusiime Mugisha.

Cleophas Mugenyi, the commissioner for basic education at the Ministry of Education says the girls need to be given a chance to continue with school. “We have all been in unprecedented times and we need to take that into account. We have asked all schools to allow all students no matter the state they are in to report to schools,” he said.

“There are now many challenges, from all different aspects of life. In order to support these learners, we need to review the guidelines, to be able to cover the current socio-political challenges.”

****

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price