Rangers live and work in areas where data is collected and possess intimate knowledge of the landscapes and species

ANALYSIS | RONALD MUSOKE | Wildlife rangers from the Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA), the country’s leading conservation agency, have showcased their ability to generate precise and reliable data on lion populations in Uganda’s Nile Delta, a critical stronghold for African lions within Murchison Falls National Park.

The findings of the study titled: “Rangers on the Frontline of Wildlife Monitoring: A Case Study on African Lions in Uganda’s Nile Delta,” were published in the journal Nature Communications Biology on Oct.15.

The study carried out between April 6, and June 19, 2022, demonstrates that rangers trained in search-encounter surveys—the scientific gold standard for lion monitoring—can provide robust and cost-effective data on lion populations, which are among the most charismatic yet imperiled species on the African continent.

The study shows that wildlife rangers, a critical component of global conservation efforts but often underutilized in scientific research, can play a pivotal role in the conservation science surrounding the world’s most attractive big cat.

“By empowering rangers and focusing on protecting critical habitats such as the Nile Delta, we could ensure a future for Uganda’s lions,” the researchers say. “This study offers a useful case study for scaling up lion monitoring efforts across Africa, using the invaluable skills of rangers to safeguard these iconic predators.”

Rangers are an underutilized resource

The researchers noted that regular population monitoring of imperiled charismatic species such as large carnivores is critical for conservation. Yet, the effectiveness of such monitoring is often compromised due to isolated surveys, limited on-ground capacity, and inappropriate methods. “Wildlife monitoring is often resource-intensive, and the utility and cost of different field protocols are rarely reported,” the researchers note.

According to the researchers, wildlife rangers are uniquely positioned to contribute to this effort. They live and work in the areas where data is collected and possess intimate knowledge of these landscapes and species. As such, their involvement not only enhances monitoring efforts but also garners governmental support for the outcomes.

“Because rangers frequently have ecological training, they represent a valuable stakeholder group for wildlife monitoring, especially in governments’ long-term conservation programmes,” the researchers add.

Moreover, because they work for governments, their involvement may generate support for the outcomes of monitoring.

“Because rangers frequently have ecological training, they represent a valuable stakeholder group for participation in wildlife monitoring, especially where governments seek to install long term monitoring programmes,” the researchers say.

The researchers say monitoring programmes that are collaborative in nature tend to build capacity, share the resource load amongst conservation stakeholders, increase spatial coverage and are often integrated into local and national conservation plans.

Furthermore, the study also compares the efficacy and cost-effectiveness of surveys conducted by government tourism rangers against traditional methods using infra-red camera traps. In both instances, the study was motivated by the desire to apply the current state-of-the-art methods for abundance estimation (spatial capture-recapture), which require unambiguous and correctly assigned individual identities.

A previous study designed to collect such data on lions made use of white flash cameras and suggested that infra-red camera traps were likely to be unsuitable for obtaining individual identities.

However, this was not quantified and warrants further investigation since infra-red cameras are often preferable as they are less likely to get stolen due to the fact that they emit much less light compared to white flash cameras. In order to provide recommendations and usable information for future surveys, the researchers quantified the cost of both the camera trap survey, and the one conducted by tourism rangers.

Murchison’s Nile Delta a critical lion stronghold

The study identified the Nile Delta within Murchison Falls National Park – Uganda’s largest protected area – as a vital area for lion conservation. The conservation area supports high lion densities, despite significant pressures from poaching and oil exploration, making it a critical priority conservation area in the country.

In the study, the researchers deployed two standard field protocols aimed at collecting data on African lions within a spatial capture-recapture framework. For the first protocol, the researchers trained Uganda Wildlife Authority (UWA) rangers in search-encounter techniques, the industry gold standard for monitoring lions.

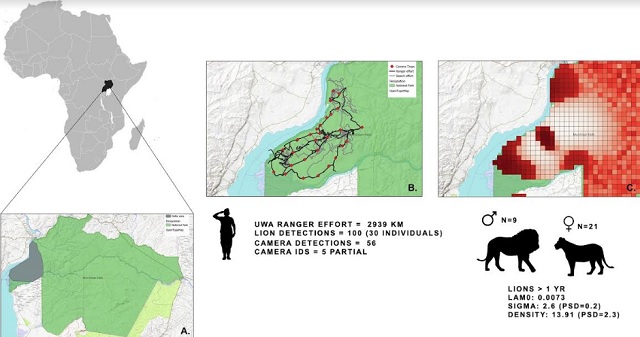

The second protocol involved deploying 32 paired stations of the state-of-the-art infra-red camera traps. During the search-encounter protocol, two rangers covered 2939km in 76 days, recording 102 detections (30 individuals) in a 256 sq km area.

With 102 detections over 76 days, the lion density in the Murchison Falls Nile Delta was estimated at 13.91 lions per 100 sq km, highlighting this area as a significant stronghold for lion conservation. While rangers were often on the front lines of wildlife protection, they were rarely included in scientific research efforts.

According to the researchers, the study is one of the first to demonstrate that rangers could effectively lead and contribute to data collection and population monitoring of threatened wildlife. “Their intimate knowledge of the landscapes and behaviour of target species make them invaluable champions for conservation,” said the researchers.

“Our results highlight the benefits of collaborating with local stakeholders (rangers) working in tandem with the tourism sector, to execute scientifically sound lion population surveys. The data collected by wildlife tourism rangers generated density estimates with acceptable levels of precision, which could likely be improved by adding more days to the sampling effort.”

Cost-effectiveness of rangers

One of the most striking results of the study was the cost efficiency of ranger-led surveys. The cost of the ranger effort was 50% lower than using remote infrared camera traps, another popular method used for surveying big cats, showing that ranger-led initiatives could be a more sustainable and cost-effective method for monitoring lions in Africa.

Despite deploying 64 infrared camera traps, the cameras yielded only two usable detections for individual identification, suggesting that camera traps, in their current form, were not yet suitable for lion population monitoring.

Incorporating rangers’ skills in future studies

The researchers argue that where wildlife tourism rangers exist, they could be a powerful addition to future lion and wildlife census attempts across the continent.

The researchers say their results confirm that the current technology of store-bought infra-red camera traps is not suitable for individual identification of lions, and therefore cannot be applied to analytical models that require unambiguous individual identities.

However, they encourage the continued testing and advancement of infra-red camera trap technology since in many instances, this may be preferable to white-flash camera traps, which can yield individual identities for lions.

The researchers say their study also shows the immense importance of the Nile Delta for African lions in Uganda’s Murchison Falls National Park, a protected area with both oil extraction and high rates of anthropogenic snaring pressure.

In an African context, no species better exemplifies this problem than the African lion (Panthera leo), the paper reads in part. “Lions are a charismatic and imperiled species, which play a significant role in consumptive industries. As such, there is intense interest in their population numbers from a wide variety of stakeholders.”

However, methods used to monitor lions across Africa have historically been inconsistent and imprecise. This is because estimating lion numbers across large spatial scales at which they exist is notoriously difficult.

One solution is to regularly deploy multi-agency teams of local stakeholders for intensive surveys using rigorous methods within smaller areas. In this manner, monitoring is not a stand-along activity, but rather a component of conservation decision-making, improving its utility in adaptive management.

The authors of the research advocate for a broader adoption of incorporating the field skills of wildlife rangers to survey lions across Africa to ensure more consistent and reliable wildlife data, which is critical for adaptive conservation management.

Dr. Alex Braczkowski, the lead author, said, “Rangers are the unsung heroes of wildlife conservation. Our co-authors, Lilian Namukose and Silvan Musobozi, have worked for the Uganda Wildlife Authority for over a decade and their deeply intimate knowledge for where lions were in the Murchison landscape allowed us to get a good idea of the status of lions in this critical area. Our study shows bringing rangers into wildlife monitoring and census efforts could be immensely powerful for lions across Africa.”

Lilian Namukose, a Uganda Wildlife Authority ranger and co-author on the study, added, “This was the first scientific study of wildlife where I directly participated and my first entry point into science.”

“Through rigorous training in three workshops across three national parks, we quickly learned to incorporate lion data collection alongside our daily field duties. We are grateful to the Uganda Wildlife Authority for the opportunity to be involved in this work,” she said.

Silvan Musobozi, a Uganda Wildlife Authority ranger and co-author on the study, said, “Rangers are arguably the closest group to wildlife on the ground and have good knowledge of animal behavior. Through capacity building and training, rangers can be better incorporated into the scientific and management process.”

Orin Cornille, the field coordinator of the Volcanoes Safaris Partnership Trust and co-author on the study, said, “Incorporating Uganda Wildlife Authority Rangers allowed our broader research team to focus on other parts of this very large national park. Their field knowledge of lion behavior meant a high sample size of great data.”

Prof. Duan Biggs, Associate Professor at Northern Arizona University and co-author on the study, concludes, “Our paper shows that by partnering with in-country conservation agencies and enabling local rangers—we can obtain a precise estimate of lion numbers at a fraction of the cost of other techniques.”

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price