Powerful politicians to blame, says Transparency International

COVER STORY | RONALD MUSOKE | Uganda remains one of the most corrupt countries on earth despite President Yoweri Museveni’s government putting in place numerous interventions to fight it.

This is the main revelation of the global anti-corruption non-profit, Transparency International, in its latest Corruption Perceptions Index report.

The report published on Feb. 11 ranks Uganda at 145 out of 180 countries surveyed. With a low 26 points out of a possible 100 points, Uganda ties with conflict-prone Iraq, Madagascar, Mexico and Nigeria. The worst ranked are South Sudan, Somalia, Venezuela, Syria, Yemen and Libya. They each scored below 13%.

According to the report, despite the various interventions such as establishment of anti-corruption units within Museveni’s Office; numerous anti-corruption interventions by different entities such as enhanced public awareness and digitalization of public services, Uganda’s global score has stagnated over the last four years.

“The stagnation stems mostly from the near absolute control of its political leaders, who benefit from the wealth they direct towards themselves, while clamping down on dissent to maintain their power,” says the report.

The Report adds: “These entrenched authoritarian governments have a firm grip on their own socio-economic systems. They shroud corrupt practices in secrecy, opening opportunities for corruption across public life, from access to public goods and services, to lack of transparency in procurement.

“With so much to lose from accountability measures and citizen participation, elites target dissenting voices, from journalists to political activists and civil organization.”

The report concludes that if the corrupt elite are allowed to maintain their absolute authority, the country remains stuck. Specifically, the report notes that Uganda’s stagnation somehow mirrors a concerning national and related global trend where most countries have made little to no progress over the last decade.

Within the East African Community (EAC) bloc, Rwanda performs best with a score of 57%. Its average score over the last six years is 53%. Rwanda is followed by Tanzania at 41%, Kenya scored 32%, Uganda 26%, DR Congo (20%), Burundi (17%), Somalia (9%) and South Sudan (8%).

The Seychelles scores highest in the Sub-Saharan region with 72%. The sub-Saharan average score is 33%. About 90% of the 43 countries in sub-Saharan Africa scored below 50%. The best ranked country globally, Denmark scored 90%, followed by Finland 88%, and Singapore 84%.

Deeply entrenched public sector corruption

The Index notes that while some African nations like Rwanda, Seychelles, and Cote d’Ivoire are making strides, Uganda continues to grapple with deeply entrenched public sector corruption that undermines development, human rights, and the fight against climate change.

“Uganda has stagnated at this score since 2022 dropping from 27% in 2020/21,” said Francis Ekadu, the Director of Programmes at the Uganda chapter of Transparency International.

“For the past three or so years, Uganda has stagnated at 26%. It’s like you have your child in school and he or she is ever coming up with the same marks,” said Peter Wandera, the Executive Director of Transparency International-Uganda, during the report launch in Kampala. “These marks are below average; they are below the pass mark.” Wandera said the pass mark is 50%.

He noted that in the past, there have been allegations that the CPI is a Western-based prism; that the assessors don’t consider the conditions in Africa. “But then when you move onto our neighbour, Rwanda, for them they are improving,” he said, “even when Uganda scored 27% four years ago, Rwanda was at 53%.”

“Rwanda is improving; it’s now at 57%. That paints a worrying scenario (for Uganda); it shows that actually in Uganda we are making little or no progress in the fight against corruption,” he said.

Wandera noted that Transparency International’s report is not rating the systems in place because Uganda has got those systems in place. “It’s not rating the interventions that the government has put in place to fight corruption, because there are quite many. But it gives a picture of the results,” Wandera said, “What are the results of the laws that have been enacted? Are they being effective? What are the results of the interventions that are being put in place? Are they being effective? The answer is a big no.”

Marlon Agaba, the Executive Director of the Anti-Corruption Coalition-Uganda, a Kampala-based non-profit says there are several reasons as to why Uganda appears to have stagnated. He says there is no political will to fight some forms of corruption, especially political corruption.

“The political will is quite limited,” he says, “We have seen the scandals that have recently come out that involve politicians; we have seen most of them not being tried.” “Even those(culprits) who are tried in courts of law, the outcome is always the same. They are always acquitted. So, there is the whole issue of political will when it comes to political corruption.”

What is the CPI?

The Transparency International Corruption Perceptions Index (CPI) is based on the views of experts and surveys from business people not the public. It is calculated using data from 13 external sources, including the World Bank, World Economic Forum, private risk and consulting companies, think tanks and others. It uses a scale of 0-100; with 100 representing very clean countries and 0 showing highly corrupt countries. The CPI captures public sector corruption, such as bribery and the diversion of public funds, and also considers how effective the prosecution of corruption cases is, the adequacy of legal frameworks, access to information and legal protection for whistle blowers, journalists and investigators. The CPI highlights the contrast between nations with strong, independent institutions and free, fair elections, and those with repressive authoritarian regimes.

Full democracies have a CPI average of 73, while flawed democracies average 47 and non-democratic regimes just 33. The CPI reveals that although some nondemocratic countries might be perceived as managing certain forms of corruption, the broader picture shows that democracy and strong institutions, civic space, and freedom of expression and assembly are crucial for combatting corruption fully and effectively. Those lacking these have very low scores.

Denmark tops CPI, again

For the seventh consecutive year, Denmark heads the ranking, with a score of 90. Finland and Singapore take the second and third spots, with scores of 88 and 84, respectively. Scoring 83, New Zealand is out of the top three positions for the first time since 2012, but it remains in the top 10, together with Luxembourg (81), Norway (81), Switzerland (81), Sweden (80), the Netherlands (78), Australia (77), Iceland (77) and Ireland (77).

On the other hand, countries experiencing conflict or with highly restricted freedoms and weak democratic institutions occupy the bottom of the index. South Sudan (8), Somalia (9) and Venezuela (10) take the bottom three spots. Syria (12), Equatorial Guinea (13), Eritrea (13), Libya (13), Yemen (13), Nicaragua (14), Sudan (15) and North Korea (15) complete the list of lowest scorers.

Uganda can do better

During the report launch in Kampala, Paul Banoba, the Transparency International Africa Region Advisor lifted the gloom on the situation in Africa noting that although Africa ranks very poorly (regional average score being 33%), that is not the total picture. He says some African countries perform well.

The top-ranking country in this index in Africa is Seychelles with a score of 72%, he says. That puts it ahead of the United Kingdom at 71% and France at 67%. Rwanda scores higher than Spain, Italy and others.

Banoba says it is possible for a country to improve. “Tanzania, 10 years ago, had a score of 31 and Tanzania today has a score of 41%. That is a 10-point increment on that index over 10 years,” he says.

“Cote d’Ivoire is similar; a 10-point movement over five years,” he says, “Seychelles, 20 years ago had a score of 52%, today it has a score of 72%.”

With over two thirds of countries scoring below 50 out of 100, the CPI underscores the pervasive nature of corruption and its detrimental impact on societies worldwide. The global CPI average of 43/100 remains low, with a majority of countries struggling to control corruption. This underscores the urgent need for concerted action at both national and international levels.

The report emphasises that corruption undermines democracy, fuels instability, and violates human rights. The vice also obstructs effective climate action, diverting resources and hindering the implementation of policies to reduce emissions and protection of vulnerable populations.

Corruption and the Climate Crisis

This year’s index also highlights the critical link between corruption and the climate crisis. “What we are saying is that let us see how we can integrate anti-corruption programmes, anti-corruption interventions into the climate change crisis. So, this is the theme,” says Peter Wandera.

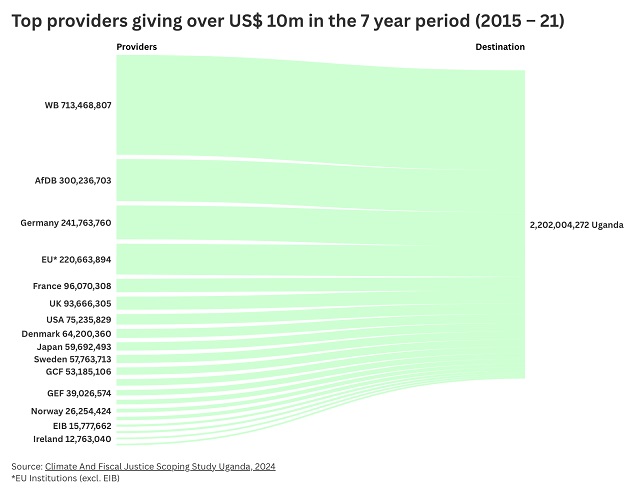

African countries require an estimated US$2.8 trillion in financing to implement their “Nationally Determined Contributions” or plans they voluntarily draft to fight climate change. However, such funding currently falls far short—and that which is available risks being undermined by public sector corruption.

Transparency International and its representatives across the world want governments to ensure that climate intervention funds are not lost to corruption.

The report says environmental crime and corruption go hand in hand. More than half of countries with a CPI score below 50 show high levels of environmental crime. For example, 88% of countries with a CPI score of above 50 have low levels of environmental crime.

According to the report, corruption makes it harder for people to speak out against climate change. It says land and environmental defenders – who are frequently at the forefront of the fight against the climate crisis – are exposed to violence, intimidation and even murder in countries where corruption levels are high. In the last five years, more than 1,000 environmental defenders have been killed, almost all of them in countries with CPI scores below 50.

In short, the climate crisis cannot be solved unless people step up the fight against corruption – and increasingly frequent and severe environmental degradation, natural disasters and climate-related instability show everyone must act now.

“This year’s analysis showed again how fossil fuel corruption undermines climate efforts, including in the United States,” says Mads Christensen, the Executive Director of Greenpeace International.

He notes that around the world, communities are demanding climate action from their governments, however, the people’s voices are time and again countered by the corrupting power of the oil and gas companies profiting from environmental devastation, who use their billions to attempt to silence critics and activists, to buy power, and to dismantle the protections that safeguard our families and our planet.

“We must urgently root out corruption before it fully derails meaningful climate action. Governments and multilateral organisations must embed anti-corruption measures into climate efforts to safeguard finance, rebuild trust, and maximize impact,” says Maíra Martini, the CEO, Transparency International.

Going forward, Transparency International notes that as the climate field is still developing, there is a unique chance to establish safeguards against theft, policy capture and other abuse. Strong collaboration between climate and anti-corruption actors is essential, with the United Nations (UN) Convention against Corruption offering a critical framework to support this work.

Transparency International is also calling for the enhancement of investigations, sanctions and protection to combat corruption. This, it says, will deter environmental crimes and reduce impunity. Access to justice can be improved through strengthening enforcement and oversight bodies – including anti-corruption bodies.

Local communities need access to grievance mechanisms, while those who speak out – climate, land and environmental defenders, and whistleblowers – must be protected from all forms of retaliation.

In addition, shielding climate policy making processes from undue influence at national, regional and international levels could lead to stronger climate action. The agency notes that reaching the highest levels of transparency and inclusivity in climate policies and finance allocation would unlock their full potential, while also reestablishing trust in climate initiatives. Creating mechanisms to detect and manage conflicts of interest – including through lobbying registers and declarations of interests – is essential to raise ambition in key climate fora such as the UN Framework Convention against Climate Change.

But also strengthening citizen engagement in climate investments could enable those affected by the climate crisis to help tailor the solutions. Transparency International says information on climate finance, projects and contracts needs to be open, accessible and disseminated in a timely way, in line with the principles of obtaining free, prior and informed consent from people affected by such initiatives.

“Inclusive accountability frameworks ensure communities are engaged throughout initiatives like the Just Energy Transition Partnerships between countries, including via oversight. This produces results that better address their needs,” says the report.

Banoba says Transparency International’s vision is to see a world in which the daily lives of people are free of corruption.

“Every time we launch the CPI, we make a deliberate effort to link that year’s results to the current issues of the year and then see how that affects the daily lives of people. This time, it’s on climate.” “How does climate change and its effects impact the countries in our region?”

Banoba says Africa is the region facing the highest vulnerability and impact from climate change and, at the same time, Africa is a region facing the highest impact from corruption.

In terms of climate change, the impacts of climate change, the sectors most affected are those where our people actually spend their time, he says.

“You might know, every Ugandan really should know, that the agriculture sector employs about 70 % of our people.”

“The other reason why climate change affects us is that our agriculture is specifically rain-fed,” he says. “So, any changes in rain patterns, there is no rain, there is a drought, then the rain comes in torrents and all those patterns affect a large section of the population and a large section of the employment sector, the labour force.”

“I need to emphasize that the twin problem of corruption and the effects of climate change on our people especially people that depend on the state to provide and support or put measures in place, the impact is quite high and costly on lives and livelihoods each time we see floods, drought and pest and disease outbreaks wiping out crops.”

“So, we would benefit very highly if all resources mobilised to mitigate the impacts of climate change are safeguarded from corruption by having very robust systems in place,” Banoba says.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price