Unlike liberalism’s core principle of Individualism, ubuntu does not believe there are primary differences between people

COMMENT | MUXE NKONDO | Ubuntu is based on a simple yet radical premise, that there are no primary differences between people. If we take that message into our politics and legal systems we can address the failings of liberalism.

Many of the forces that have shaped history have been underpinned by a false belief that there are fundamental, primary differences between people. Imperialism, apartheid, and patriarchy created hostility, contempt, condescension accompanied by social, economic, and political mistreatment. The belief in primary difference is not restricted to the powerful. It is also found amongst the oppressed and excluded.

There is no scientific backing, nothing to justify the broad range of beliefs, attitudes, and practices based on the perception of difference. Research across various disciplines shows that belief in primary difference has no basis, no legitimacy whatsoever. Reference by those who would belief the difference was real to a metaphysical reality has been exposed for what it is – a fallacy, a myth. No scholar has been able to establish the reality of racial, ethnic, or gender essence. It is based on ignorance, irrationality, and unreasonableness.

What can be done to convince a racist, a tribalist, or a patriarch, for example, that recognition of a common humanity would enhance the possibilities of peace? This is an internal and social phenomenon. It is a matter of attitude, thinking, and behaviour. The good news is, that it is possible because human beings are capable of empathy and fairness, which moves human behaviour beyond egotistic desire and appetite.

The idea of primary difference and its political sociology is complex. It takes identity difference for granted. It presumes that human populations can be partitioned into distinct kinds based on their cultural and physical difference. Racial, ethnic, and gender differences make no sense without belief in primary difference. It is not the presence of objective physical differences that creates races, ethnic groups, and gender enclaves, but social interpretations upon such differences can create antagonism. It is categorical in that it takes for granted the presence of identity groups as natural kinds, not historical and contingent constructions. It is also one-dimensional.

Primary difference relegates gaps and asymmetries between groups to a realm of primary, antagonistic differences. With the differences regarded as fundamental and insurmountable, individuals in such groups become irredeemably negative to each other. Other people in other groups are not viewed as companions but, at most, as means to ends. Nothing can be learnt from such people, the thinking goes. The only way to deal with them is through power and violence, both subjective and systemic.

But as we reject the idea of primary difference, we should also avoid rejecting the individuals who perpetrate it, dismissing them as monsters, in-educable and unsociable. If we reject them, we will just be one more example of intolerance, leaving no space for learning and mutual recognition.

The politics and limits of liberalism

Liberalism’s constant enlargement of its sympathies without fundamentally transforming how the self relates to the other, its moral philosophy, has now found its limit. It is not enough for liberalism to pride itself on constantly extending sympathy and adapting itself to the other. Tolerance is not enough; it leaves the egotistic self as the centre of reference to which the other is just a blank page on which to inscribe its story. This is the challenge; to make the self-open, cordial, flexible, and responsive to the other.

Individualism, a core principle of liberalism, maintains that the rights of individuals are fundamental and justifies the actions of coercive government as promoting those rights. Ubuntu maintains that the rights of individuals are not fundamental and that the collective can have rights that are independent of and even opposed to what liberals claim are the rights of individuals. The principle of secondary difference takes equality and justice to be the basic ideal and justifies power insofar as it promotes the common or public good.

The self and the other

A major principle of the African philosophy of ubuntu is, in short, take care of yourself but care for the next person as well. But for us now, in the grip of individualism, this notion is rather obscure and faded. Without doubt, the liberal system overemphasises individualism at the expense of social cohesion. A whole field of antagonistic relations between the self and others have been constructed and institutionalised world-wide, grounded in the liberal notion of individualism.

To shift this balance, we have to make sure that the new values and principles have to be inscribed in policy and law. They have to be inscribed in a Bill of Rights and a Bill of Responsibilities to ensure implementation, just like liberal principles have been.

But we are not naïve – a cosmopolitan social democratic community is hard to achieve. It is work in progress. Changing people’s beliefs and attitudes is a very tall order, but the failure of liberalism in modern history points in this direction. Consequences on the lives of people must be the measure of leadership. It is learnable, our being allows it. The happiness and well-being of all require it. It will enable us to move in and out of our identity spaces: the translatability of language and culture as they move in space and time proves that much. New vocabularies are possible.

*****

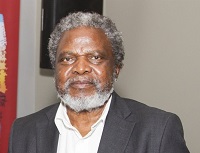

Muxe Nkondo was a social policy, national strategy development, and discourse analysis scholar and practitioner, former Deputy Vice-Chancellor (Academic Affairs) at the University of North (now Limpopo) and Vice-Chancellor of the University of Venda, South Africa, a Harvard Andrew Mellon Fellow in English. He passed away on Sunday, August 18, 2024. This article was first published on February 13, 2024.

Source: LSE Firoz Lalji Institute for Africa

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price