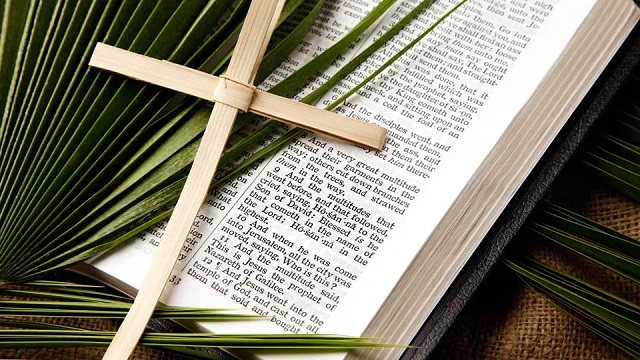

COMMENT | | Today is Palm Sunday, marking Jesus’ triumphal entry into Jerusalem. Crowds gather, laying down cloaks and palm branches, singing “Hosanna!” It is a moment of joy and symbolism, filled with expectation. Yet it is also full of tension, the very same people who welcome him will, days later, call for his crucifixion. The procession is sacred, but it foreshadows pain.

Symbolic processions like this are not unique to Christianity. Across Africa, ritual entrances, public ceremonies, and spirit-inviting processions have long played a central role in religious and communal life. In these traditions, movement itself becomes meaning. Whether it’s welcoming an ancestral spirit, initiating a new leader, or celebrating a seasonal rite, the act of journeying, often accompanied by dance, drumming, and songs, is a moment of collective spiritual expression.

In many African societies, sacred processions mark a threshold, a crossing from the ordinary into the sacred. When an ancestral shrine is being renewed, when rainmakers are called, or when a spirit is being welcomed into the community, there is a deliberate and meaningful movement of people, objects, and energy. Just as Jesus rides into Jerusalem on a donkey, not as a warrior, but as a humble king, African rituals often contain hidden meanings in the choice of symbols, gestures, and paths.

For example, in Buganda, a royal procession is never merely about arrival. The route taken, the order of participants, and the way the king steps onto sacred ground all carry spiritual and political significance. To enter is to signal something, a claim, a change, or a confrontation. Similarly, Jesus’ entry was not only a fulfilment of prophecy, but a symbolic disruption, a king arriving not with an army but with peace, challenging the very idea of power.

Palm branches, in biblical times, were signs of victory, peace, and honour. But they are also fragile. They dry quickly. In African cosmologies, such symbols would never be dismissed as mere decoration. Plants, animals, and natural elements used in rituals are chosen carefully, each one with meaning. The fragility of the palm might, in fact, be the point: that glory fades, and human praise is fleeting.

Both traditions understand that the power of symbols is not just in what it shows, but in what it evokes. The donkey, the branch, the cloak, the song, these are not background details. They are the message. In African rituals, too, symbolism is layered and alive. A horn may represent ancestral voice; a gourd, fertility; white chalk, peace, or rebirth.

What also connects these traditions is the emotional arc. The same crowd that praises Jesus later demands his death. In African rituals, joy and danger often walk together. A procession may begin with celebration but lead into testing, sacrifice, or spirit possession. There is rarely comfort without cost.

Palm Sunday reminds us that sacred entry is not an end in itself. It is a beginning, a crossing into deeper conflict and, ultimately, deeper truth. In both biblical and African traditions, processions are not performances but revelations. They show who we are, what we hope for, and what we fear. They force us to ask: What are we welcoming? And are we ready for what follows?

As we wave our metaphorical palms, let us remember the path we walk. It is not a parade but a procession, one that calls for humility, honesty, and courage. The true meaning of entry is not in the welcome but in the journey that follows.

****

Gertrude Kamya Othieno | Political Sociologist in Social Development (Alumna – London School of Economics/Political Science) | Email – gkothieno@gmail.com

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price