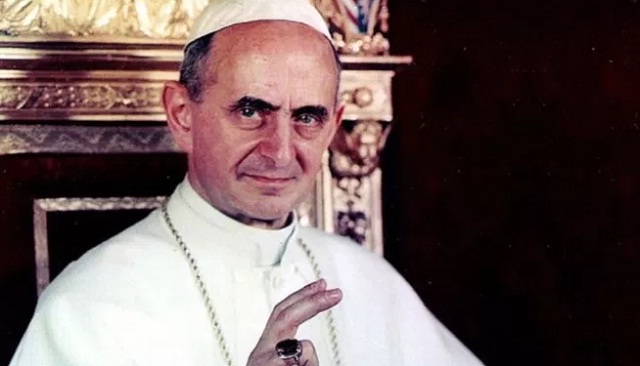

Reformist pope Paul VI will soon be a saint

Kampala, Uganda | AGENCIES | Pope Paul VI, who oversaw the sweeping “Vatican II” reforms of the Catholic Church in the 1960s, will soon be made a saint, the Vatican announced on March 07.

Pope Francis signed decrees on March 06 giving the go-ahead for the honours on the basis of miracles attributed to pope Paul VI. Pope Francis put Paul VI on the path of sainthood by beatifying him in October 2014. Following the announcement, we reprint this story on his life and legacy that originally appeared in America Magazine on Aug. 19, 1978.

Each pope in the history of the church has brought to the special challenges of his era his own special gifts of intellect and spirit. The historical character of his tenure in the chair of Peter is then determined in the dialectic of the person and the time. In many instances, the institution of the papacy itself has been redefined, subtly or radically, as a result. This recurrent interplay of individual, institution and historical moment was never, in the history of the modern papacy, more forcefully and dramatically at work than during the papacy of Paul VI.

Has any pope reigned over a more volatile age than Giovanni Battista Montini?

On June 21, 1963, when the then Archbishop of Milan was elected by the College of Cardinals to head the Roman Catholic Church as the Bishop of Rome, few realized the convulsions that would wrench both church and world in the next decade. In less than five years, John XXIII had humanised the papacy and launched an ecumenical council that captured the imaginations and raised the hopes of many outside the Roman Catholic Church, as well as within.

The public ordeal of John’s final passion and death had evoked an extraordinary wave of affection toward the man and, inevitably, sympathy for his church. The process of aggiornamento—bringing the church up to date, opening its windows and transforming its face—promised a newer, more vital and more positive relationship between the church and the modern world. And that world, though surely not without its dangers, seemed an inviting place; its memories and its fears of war were for the moment dimmed, its economy steadily expanding in the industrialised nations, its confidence in itself and its own rationality typified by the attractive American, also named John, who brought to the White House and the leadership of the Western world the buoyancy of hope.

Yet, only a few months later, the young president of the United States was murdered, the first in a series of political assassinations that would be succeeded by an epidemic of terrorism that mocked the rationality of the political process. A distant struggle in Vietnam became a global preoccupation, and the proclaimed end of colonialism seemed illusory when the realities of world poverty were faced. In a time, then, of pervasive social change, in a time of violence and protest, Paul VI was asked to lead his church through the final sessions of the Second Vatican Council (1962-1965) and into the years that followed, when it would be his responsibility to implement the reforms that embodied the principal theme of the council: the church in the modern world.

The council document that dealt most explicitly with this central theme began with the words “joy and hope,” but that joy and hope could never be unthinking or uncritical. The church was being called to express its solidarity with the world, but never its conformity to the world. The church would change and yet remain itself. The Gospel would be incarnated in different cultures and in different times, but it would always be the Gospel of Jesus Christ. Throughout his papacy, Paul VI was caught at the center of these tensions that are the very nerves of Christian faith. Inevitably, he would be criticised by those tugged more by one current than another. Unfairly, he would be characterised as ambivalent and indecisive by those less sensitive to, or even oblivious of, the paradoxes of the Incarnation.

During the sessions of the council and in the years immediately following, Paul VI overcame the resistance of reactionaries and implemented the reforms established by the council in the areas of liturgy, church governance and the attitudes of Catholics toward other religions. Liturgical reform was not always and in all places executed with the greatest grace, but it was clear as the years moved on that Catholic spirituality was being enriched by a greater sense of Word and Sacrament.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price