Shs160bn project from COP21 commitments at stake

NEWS ANALYSIS | Dicta Asiimwe | A project intended to help subsistence farmers in Butaleja district, eastern Uganda, cope with climate change impacts is at risk of failure as some would be beneficiaries have not yet left the wetlands where they grow rice. Two and a half years to the end of the project, restoration work is yet to start.

Butaleja district sits on a floodplain in the shadow of Mt Elgon in eastern Uganda and wetlands make up 40% of its land. But its water table is shrinking, farmers are getting one rice season instead of two, and its streams flood quickly and dry out equally quickly leaving animals and crops thirsty for water.

Lamula Were, the Senior Environmental Officer for the district, says its water situation should not be this way. She blames the changing climate and human occupation of wetlands, which are the natural water reservoirs.

“Getting only one rice season is becoming normal, yet we used to have two good ones,” she says.

Environmentalists say wetland restoration in Butaleja is a headline initiative under a project whose intention is to improve ecosystem services.

The Green Climate Fund (GCF), which is funding the project alongside the Uganda government, says improved ecosystem services will lead to replenished ground water, flood control and a better life for smallholder subsistence farmers.

Joseph Malinga the Spokesperson for GCF projects in the Ministry of Water and Environment (MWE) says the project has gone according to plan in districts such as Palisa, where the government was able to build two small irrigation schemes for farmers, but in Butaleja, things have not been as smooth.

“We are now registering the people who are affected, before we can get them to leave the wetlands for restoration to start,” says Malinga.

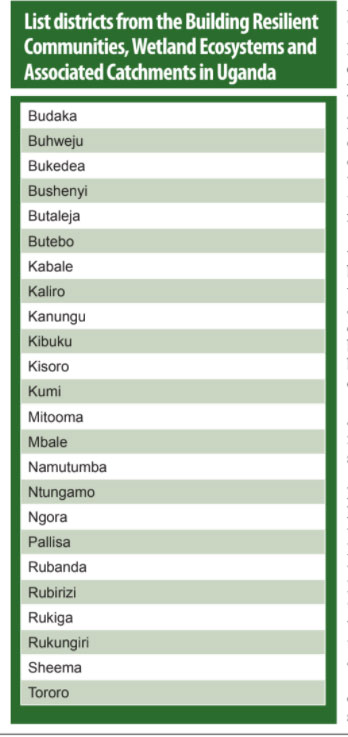

Scheduled to end in June 2025, the Building Resilient Communities, Wetland Ecosystems and Associated Catchments in Uganda project just has two and a half years left on its eight year implementation period.

Mr Malinga says the government only has a short time to work for restoration, as MWE is still grappling with how to deal with the population that is increasingly dependent on the wetlands in Butaleja for rice growing.

Compensation issues

Ms Were says that some parts of Butaleja, which the population used to think, were uninhabitable have since been occupied.

“When you take people through their historical maps, the population itself tells you, most places that flood or are along river banks have been encroached on. The population tells you such places were not habited in the 10 or 20 years back. Increased population has a very big impact on our wetlands and the environment,” she says.

Poor agronomical practices coupled with population pressure, which leads to over cultivation of the same plot of land, also lead to soil erosion.

“All the fertile soils goes to the wetland so you find that when they plant in the wetland they get bigger yield, so most of them will rush there,” she says.

Reclaiming the wetlands to plant crops has shrank the water tables in several parts of Uganda, which is why Uganda pitched to GCF the building of resilient communities, wetland ecosystems and associated catchments project. The government is implementing the project in Butaleja and 23 other districts in parts of eastern and western Uganda.

As per the Wetlands, Riverbanks and Lakeshores Management Regulation 2000, wetlands in Uganda are public land. The law means that any activity in the wetland should be approved either, by the National Environment Management Authority (NEMA) or by the local government.

This is why the project affected population in Butaleja will not be compensated. This is a major cause of friction with the population.

Malinga says despite the law’s dictates, individuals in Uganda still own wetlands and in the western part of the country, where freehold is the commonest land tenure system, the Ministry of Water and Environment is negotiating with individuals to allow for the establishment of community irrigation and aquaculture projects.

He also says farmers are receiving apiary, piggery, craft making skills and fish projects, as income generating alternatives to growing crops in wetlands.

GCF is providing $24.1 million (UGX88.9billion) for the project, while the Uganda government is funding the remaining $20.2 million (UGX74.3billion).

GCF is funding the project because it is one of the agencies designated by the Conference Of Parties (COP 21) in Paris to manage a kitty of $100 billion (Shs367.6 trillion) that advanced economies are supposed to mobilise every year for developing countries to finance climate change adaption.

As it has been said severally and most recently during COP 27 in Egypt, advanced economies are barely meeting their obligations to developing countries. Nevertheless, GCF is funding districts in Uganda to restore wetlands, create small irrigation schemes, and provide farmers with inputs to start alternative sources of income.

Unhappy farmers

Musa Hasahya Kasera, a resident in Busaba Sub-County is a typical farmer targeted by the project.

He says he is unhappy with the government’s decision to chase him and other farmers out of wetlands, as it affects people’s livelihoods.

“My two children missed their primary leaving exams because I do not have enough money, since I didn’t grow rice this year,” says Kasera.

Kasera has a very large family and says he has many expenses. He has had 102 children and 98 of these are alive. The children and their wives, his own spouses who have now reduced from 12 to 6, and the grandchildren who are now 578 in number, mostly depend on the land.

The exception is the one son with three wives to whom Kasera bequeathed his butchery. Until 2014, when a quarantine was declared in Butaleja due to a foot and mouth disease outbreak, Kasera owned a butchery. The quarantine meant butchery owners who wanted to keep their businesses running, had to start driving outside of Butaleja for animals to slaughter.

“I am old and sickly and the life of sitting atop a cattle truck did not feel suitable, so I retired and left the business to my son,” he says.

By the time he retired, Kasera says he had distributed most of the 162 acres (65.6 hectares) of land that he acquired during his working years. Following his retirement, Kasera started renting gardens from people whose land included wetlands to grow rice. He would then use members of his family to grow, maintain and harvest the rice, which he would then sell. The money went to catering for things such as school fees and other household needs.

He agrees with Ms Were that the number of rice growing seasons are reducing and says he did not grow rice in 2022 because he heeded the call to vacate wetlands, but adds that his colleagues who ignored the government only got one rice season.

Kasera blames reduction in rainfall and water in wetlands for the one rice season, but does not associate these problems with actions of farmers like him.

Population pressure

Ms Were explains that although the average family in Butaleja does not require as much land as Kasera’s clan of 98 children, 578 grandchildren and six wives, there are people expanding their holdings into would be protected areas like wetlands, because it is part of the struggle to survive.

“People have been forced to move to wetlands, because when you assess the landholdings, many families own less than an acre. Yet the average family has about ten people in a household, so wetlands are viewed as an alternative piece of free land,” she says.

Some experts suggest that compared to the global situation, Uganda should be doing a better job protecting sensitive ecosystems, which include wetlands, as the country does not have a real population congestion problem.

A data sheet produced by the Population Reference Bureau (PRB) shows that globally land holding stands at 2,168 people per square kilometer of arable land.

PRB, which has produced population statistics since 1962, shows that Uganda has 685 people per square kilometer of arable land. While this is slightly high when compared to countries such as Tanzania and South Sudan, Eastern Africa also has countries like Rwanda and Djibouti, where the population per square kilometer of arable land stands at 1,196 and 56,042 respectively.

According to the World Bank, the problem for Uganda is that the country has failed to make it possible for the population to move away from dependence on agriculture, as the main source of employment.

The World Bank says in its report Growth, Trade and Transformation study that the proportion of small household farms with less than two hectares of land rose from 75 to 83 per cent between 2006 and 2016.

“As a result, the average net land operated in Uganda fell from 1.7 to 1.2 hectares per household, thus reversing the trend toward larger farm holdings, which are more likely to commercialise due to economies of scale and ease of adopting modern technologies,” reads an excerpt from the 2022 report.

Lynda Birungi a Service Provider with Reproductive Health Uganda says Uganda’s pressure on the land comes from the high birth rate.

According to PRB’s data on Eastern Africa, only Somalia has a higher birth rate than Uganda. There are 44 live births for every 1,000 people in Somalia compared to Uganda’s 37.

Ms Were says despite opposition from members of the public, wetlands restoration is important because the district’s water table is shrinking.

Ms Were explains that Butaleja is currently experiencing a moderate version of the situation in Karamoja. When it rains in Karamoja, a semi-arid region in north eastern Uganda, streams quickly run through the region but shortly afterwards, the Karamojong struggle with water shortages.

She says farmers reclaiming wetlands to grow crops have created a situation where water is available during the rainy season but is not available in the dry seasons.

“During the dry season, it is common to find long lines of people waiting in line to fetch water from the few functioning boreholes,” she says.

In a district where wetlands make up 40% of the land and is a floodplain for rain water from Mount Elgon, she says water shortages should not be a regular problem. The most recent water shortages affected Butaleja, Kibuku and Budaka districts in March 2022.

To end the water shortages, the wetlands which are the natural water reservoirs have to be restored. For this, Malinga; the GCF project spokesman says, the project implementers will block the water drainage channels that farmers seeking to reclaim the wetland for rice growing had opened. This will enable the water to return to its natural flowing levels. Once the channels are blocked, Malinga says, wetland plant species that had been depleted will be reintroduced.

“To grow and monitor the replanted species requires time,” says Malinga. For now it appears, however, the restoration project is running out of time.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price