How the model is built

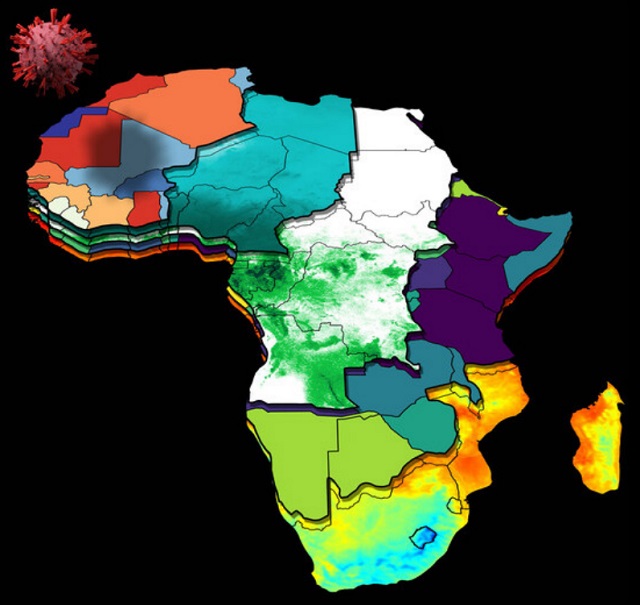

The scientists used a relatively simple model, by mathematical standards, to base the computer codes. They incorporated the daily case reports from each country, as well as the characterisation of the Human Development Index for each country, population, the stringency of social measures to control the infection, and meteorological data. They took into account the cases in neighbouring countries, as well as whether the country is landlocked.

Their model used the case numbers reported up to and including the previous week, to predict the case numbers in the week ahead.

The model included past weather observations of temperature, rainfall, and specific humidity. Some of these environmental factors have been implicated in COVID-19 transmission outside of Africa. In a study published in August 2020, it was found the number of locally acquired COVID-19 cases in the Sydney area of Australia increased as the air became drier. That added to a growing body of evidence that identifies a link between humidity and COVID-19.

The scientists also modified the weather data for each country by adjusting for population. In Algeria, for example, where much of the population lives along the cooler, wetter coast, they emphasise or weight the weather data in proportion to where people live (and ignore weather data over unpopulated desert).

They took into account cross-border flow of goods and commerce, since for landlocked African countries, this is their lifeline for goods and services.

It is difficult to obtain population mobility data for Africa, so they used the cases in all other countries to test whether those cases were associated with the next week’s cases in nearby countries. This proved very effective.

+They factored in the economics of different countries, as well as the evolution of real-time governmental stringency policies such as lockdowns and border closures.

And then they needed to see if they could get an understandable summary of the current state of the pandemic in Africa, and whether predictions a week or so ahead were accurate compared with the actual measured case numbers.

From predictions to policy

The predictions were much more accurate than they had anticipated. They employed a rigorous way of scoring predictions for each country. Only for a few countries were these predictions inaccurate (Burundi, Cameroon, Somalia, and Botswana). To visualise these predictions, we created a set of tools and graphs that are very easy to interpret. A policy person needs to see what the present situation is, how that current state got there from past events, and what will happen in the future. The scientists created websites that enable anyone to use a computer mouse to select their country, or the continent, and see the results of the model. No math or PhD required.

For the technical scientists in other countries or the global agencies, they are sharing their full code. They wrote this code in free open-source software, and all the data that the model uses is from free open-source websites, so that there are no barriers to implementation for anyone.

Their methods stress data that is predictive, and automatically ignores data that is not contributing to an understanding of the cases next week. This is an old trick in economics, and the scientists found that it works very well in predicting infectious cases.

The publication contains links to computer code that runs the model, and to the graphical display of these findings, for anyone to use.

According to the scientists, their colleagues in Uganda are finding this model useful in predicting cases a week ahead. They are using it to help inform social policies and lockdowns as they track the effect on cases, and plan for reopening as case pressure eases. Because the effect of control measures is delayed by a period of weeks, prediction enables better policy planning. But like so many things in nature, such as the weather, predictions beyond two weeks are often very uncertain.

Looking ahead

One of the clear implications from these findings is that pandemics are crises that no country can best manage on its own. The scientists encourage neighbouring African countries to share data and cooperate on travel and border management.

This pandemic will end through massive vaccinations in Africa. Until billions of additional safe and effective SARS-CoV-2 vaccines become available for Africa, predictive methods such as this to help inform policy will be needed.

****

Source: the conversation

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price