Eliminating misconceptions and offering solutions

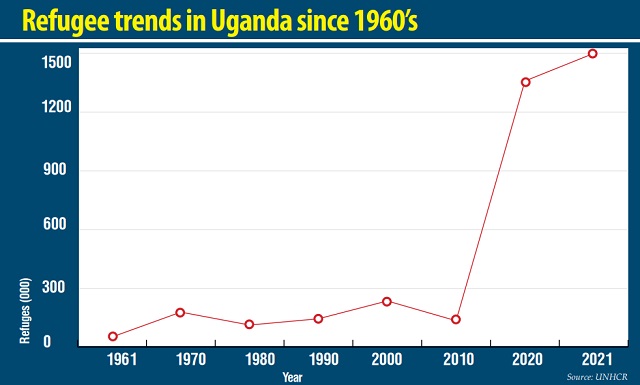

Kampala, Uganda | ISAAC KHISA | With 1.5million refugees, Uganda is the top refugee-hosting country on the African continent and one of the top five hosting countries in the world. Although the country has a relaxed policy which allows refugees to live outside camps, the country also has 48 refugee settlements, most of which are in areas experiencing the worst forms of environmental degradation.

Based on this, a section of environmental protection agencies, ministries and the non-governmental organisations have always said the influx of refugees in the country is a key contributor to the environmental degradation.

The National Environment Management Authority (NEMA in its latest State of the Environment Report for 2018-2019 states that soil and water have been polluted in refugee occupied areas and neighbouring natural resources such as Bugoma Central Forest Reserve and others face depletion.

But it offers limited statistical information to support the assertion. This is because, unlike in other countries, refugees in settlement areas share resources like wood fuel, land, water, health and education services with the host communities.

To assess to impact of settlements on the environment, The Independent carried out a month long investigation in the refugee occupied areas of Bidi Bidi in Yumbe District, Nakivale and Oruchinga in Isingiro District, Kyangwali in Kikuube District and Rwamwanja in Kamwenge District among others.

The objective was to eliminate misconceptions and also probably help to come up with proper measures to conserve the environment amidst refugee influx.

Business blamed

In Yumbe District, which hosts about 240,000 South Sudan refugees at Bidi Bidi Settlement Refugee Camp in five zones covering the sub counties of Romogi, Kululu, Odravu, Ariwa and Kochi, areas that were once covered with trees and tall grass are now huge empty spaces dotted with young trees. Sand mining and stone quarrying are rife. Most of this is, without evidence, blamed on refugees.

But a forest extension worker told The Independent that environmental degradation was happening even before the arrival of refugees in 2016.

Habib Edema Hussein said locals were already using the available natural resources for cultivation, charcoal production, timber, firewood in the area even before the influx of refugees.

“When you look at the individual homes and the settlements, people are using firewood and charcoal as source of fuel. It is only that the rate of degradation increased because of the increase in population in addition to influx of refugees,” he said.

“We (also) have prominent business people who deal in logs of endangered tree species like Afzelia Africana and Mahagony despite the local council’s ban. Business men collaborate with landlords to cut those trees and since it’s an illegal deal, such people don’t come to our offices for clearance as claimed by some people.”

Muhammad Anule, an elder residing near Bidi Bidi Refugee Settlement Camp told The Independent that before population increase in the district and refugees’ influx, the impact of the destruction was not much felt because of the low population.

“Now the claim that refugees are behind the massive destruction of the environment is because their arrival led to an increase in population exerting pressure on the environment,” he said.

Patrick Aleko, a refugee who is now trading in tree seedlings at Bidi Bidi settlement said the problem has been caused by both nationals and refugees.

“We have the host community that is living with us and so the pressure on the environment has been a combined one,” he said. He said refugees and nationals compete for wood fuels for cooking, logs and construction materials such as grass.

“However, we have to make sure that the environment in which we live is conducive and we should ensure that the depleted environment is replaced,” he said as he tended his tree seedlings.

Rashul Mawa Ijoga, LC III Chairperson for Barakala Town Council that hosts Bidibidi Zone One settlement added that business men who deal in timber and logs are the biggest threat to environmental degradation in the country’s northern region.

He said traders target the old and endangered tree species that have stayed for over 100 years in disregard to their contribution to the environment.

“The refugees can’t be blamed for the destruction of the environment leaving out the host community. The community assumes that the land where the refugees are settled belongs to them and most often go into the settlements to cut the big trees like Afzelia Africana and Mahagony,” he said.

“The local community are the ones behind the logs and timber business. No one outside the refugee hosting areas can locate places with endangered tree species but it is the village local councils and the local community exposing such tree species to businessmen,” he added.

Mawa, however, said stone quarrying has always been done by the refugees.

According to The Independent’s investigations, the same scenario is replicated in other areas around Nakivale and Oruchinga Settlements Camps, Kyangwali Settlement Camp, Kyaka II Settlement and Rwamajja Settlement Camps and others. Only in Kiryandongo District is different. Here the vegetation destruction happened in preparation for arrival of refugees from 2013 to 2017.

In the Nakivale Refugee Settlement Camp located in south western part of the country and hosting about 145, 200 refugees from Rwanda, Democratic Republic of Congo, Somalia, Sudan, Ethiopia, Kenya and Eritrea, the Lake Nakivale Wetland was well protected before 1994 and the main human activities that used to take place were cattle keeping, fishing and harvesting of wetland materials for domestic use. Today, the settlement on the edge of the wetland faces poor human waste disposal and water quality degradation.

Some of this is documented in a study published in the African Journal of Environmental Science and Technology in 2013 dubbed ‘The cost of poor land use practices in Lake Nakivale Wetland in Isingiro District, Uganda.’

But according to Shallon Busingye, the chairperson at the Nakivale Lake Community restoration sub-project, most of the degradation has not been caused by refugees but by nationals who encroached on the government land meant for refugee settlement.

She says this happened over time because of shift in land use practices by the locals from cattle keeping to crop farming.

Busingye says, over time, locals have taken to large-scale cultivation of maize for commercial purposes. As result the wetland was encroached-on to create more areas for food production, human settlement and urbanisation.

The remaining livestock has also degraded the shallow parts of the wetland, flood plain and steep slopes of hills around Lake Nakivale Wetland, leading to soil erosion and subsequently, siltation of water bodies in the area.

In Kyaka II settlement camp which hosts more than 125,000 refugees; majority from Democratic Republic of Congo, there has been increase loss of tree cover.

Refugees not to blame

Latest report published jointly by Food and Agriculture Organisation of the United Nations, World Bank, State and Peace building Fund and the Norwegian Ministry of Foreign Affairs dubbed “Assessment of Forest Resource Degradation and Intervention Options in Refugee-Hosting Areas of Western and Southwestern Uganda in 2020, states that the increment in tree cover loss in Kyaka II settlement is not linked to the arrival of refugees. Although it was observed way back in 2017, it happened a year before the influx of Congolese refugees.

And, the report notes, that the overall tree cover loss over the period 2001-2018 was more pronounced in the 15km buffer from forest to refugee camp which is accessed by the locals than in the 5km buffer that is accessed by refugees. According to the researchers, this suggests a stronger association of the actions of the locals to the degradation than refugees.

The report states that within the 15 km buffer, 12,093 ha of tree cover was lost between 2001 and 2018, with nearly half of this loss (about 49%) occurring in areas where natural forest was converted to other type of land uses.

Similarly, the study found no consistent link between tree cover loss and the presence of refugees in Rwamwanja Refugee Settlement. Statistics available indicate that within the 15 km buffer zone, 6,915 ha of tree cover was lost between 2001 and 2018. This is contrary to the 5km buffer zone standard where the refugees reside to the nearby forest cover.

In Kyangwali Refugee Settlement Camp, which hosts more than 133,000 refugees, refugees have always descended on the restricted Bugoma Forest Reserve mainly for wood fuel and construction poles. But nationals and the so-called investors descend on the same Bugoma Forest Reserve to harvest trees for timber, charcoal and expand land for commercial agriculture.

One such investor is Kinyara Sugar Company; which through its sister company Hoima Sugar is erasing the 22 square kilometer, Bugoma Central Forest Reserve, to pave way for sugar cane growing amidst protests from environmentalists, with the Uganda People’s Defence Forces (UPDF) providing security.

Multiple sources also told The Independent that Bunyoro Kitara Kingdom, which is in support of the sugar cane project, has contracted a private company to fell big trees for timber and charcoal production to enable Hoima Sugar start sugar cane farming in the forested areas. However, The Independent could not independently verify the claim.

However, trucks loaded with timber and charcoal destined to urban centres, is now a common sight in disregard of the anticipated negative impact of environmental degradation to the population.

No Environmental Impact Assessments

Uganda’s history of hosting refugees dates back in the colonial rule in which the colonial government laid the groundwork for self-reliance policies.

The British government in the 1940s used Ugandan territory to host around 8,000 polish refugees during the Second World War. The Nakivale settlement established in 1959 is now Africa’s oldest refugee camp.

Currently, Uganda hosts more than 1.5million refugees; majority from South Sudan, DRC, Burundi, Somalia and Rwanda among others, according to the United Nations High Commission for Refugees (UNHCR).

This makes the east African nation the top refugee-hosting country on the African continent and one of the top five hosting countries in the world besides Turkey, Colombia, Pakistan and Germany.

The country has been praised for promoting an open door policy to refugees, the reason for a large inflow of refugees in the region.

Despite this, the country has not undertaken any Strategic Environment Assessment (SEA) of the refugee settlement programme. Citing limited financing and human resource constraints, NEMA says in its 2018-2019 report on the state of environment that the establishment of these settlements is done without requisite approvals and clearance; including Environment and Social Impact Assessment (ESIA) certification, land use and physical development plans and consideration of the carrying capacity.

The environmental protection body says, for instance, of the 48 refugee settlements, only three have ESIA certification. But two certifications were undertaken after establishing the settlements, a situation that restricts monitoring, inspections and related enforcement to post settlement scenarios.

NEMA argues that although all the refugee hosting districts have been able to benefit from the governments interventions through various projects such as the Development Response to Displacement Impact Project (DRDIP), engagement and support to national environment agencies as initially conceived has not yet been realised. It says this has fueled tensions between refugees and nationals for the available natural resources.

“A deliberate strategy to engage national environment management agencies is thus needed for realisation of the projects` environmental targets,” the NEMA report states.

DRDIP has since 2015 targeted infrastructure development, improved livelihoods and environment protection in districts hosting refugees. The Phase I had funding of US$50 million and Phase II had US$150 million for five years from 2019.

Government agencies respond

NEMA Executive Director, Dr. Barirega Akankwasah told The Independent in email that refugees may not be the biggest degraders of the environment but their arrival comes with additional resource requirements such as energy, construction and water.

“The refugee influx increases competition with the nationals for the already stretched natural resources,” he said.

Barirega, however, said what is important now is to cushion the environment from refugees’ influx and the national population pressure.

“This can be done through establishment of woodlots for supply of energy, extension of piped water, technical guidance on best land use practices, continuous education and awareness and provision of shelter that require less cutting down of trees such as tents instead of makeshift huts,” he said.

Barirega said educating, monitoring and supporting refugees in best environment management practices are critical. But he said NEMA has not been able to do this because of lack of money, personnel, mobility equipment, and environment monitoring equipment.

New interventions

However, not all lost. Enock Twagirayesu, a refugee of Rwandese origin who is the chairperson Nakivale Green Environment, a refugee environment advocacy Community-Based Organisation based in Isingiro District, says they have so far planted close to 60,000 trees away from the buffer zone – that is 200-meter radius from the lake that is meant to remain human activity free.

He says the trees will avail them with firewood and timber for building. “Before, we were planting sweet potatoes, tomatoes plus other vegetables and our gardens would stretch up to within the lakeshores. Since we started observing the buffer zone, the water levels have increased, with the lake extending its shores into the buffer zone,” he said.

“We have tried to restore the lake. Here we have planted trees, wetland restoration and demarcating the lake plus sensitizing the communities on the need to conserve the lake,” Akiteng Constance, an Environment Assistant officer in Nakivale Refugee Camp told InfoNile online platform.

Rashul Mawa Ijoga, LC III Chairperson for Barakala Town Council that hosts Bidibidi Zone One in Yumbe District said they are working with various stakeholders including non-governmental organisations to restore degraded environment through tree planting initiatives.

He said through OPM’s DRDIP, trees have been planted for wood fuel in various sub-countries in Yumbe District just like it is being done in other refugee hosting communities countrywide.

Julius Muchungusi, the head of communication in the Office of the Prime Minister (OPM), which acts as a coordinating entity of the refugee crisis, said NEMA has a constitutional mandate to carry out environment impact assessments countrywide; including around refugee communities.

He told The Independent that NEMA’s failure to act “means that NEMA is simply reporting itself”.

He said, fortunately, NEMA’s mother body; the Ministry of Water and Environment, is usually involved in the OPM affairs in relation to environment.

“NEMA is well represented,” he said.

****

Reporting for this story was supported by a grant from the African Centre for Media Excellence (ACME), with support from the European Delegation to Uganda.

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price

The Independent Uganda: You get the Truth we Pay the Price